Alastor by P. B. Shelley (1816)

O F THE LLEWELYN Davies boys who were the inspiration for Peter Pan, Michael was J. M. Barries favourite. We all knew Michael was The One, wrote his younger brother Nico. Barrie loved him with a great love, as Michaels friend at Eton and Oxford, Robert Boothby, recalled.

The Real Peter Pan is the story, both joyous and tragic, of a beautiful boy who was chosen by Barrie to be his gateway to the magical world of childhood, which he longed to recapture, and to the strange spiritual world of his later work.

Unlike Alice Liddell and Lewis Carroll (in the context of Alice in Wonderland), and Alastair Grahame and Kenneth Grahame (The Wind in the Willows), Michael was not simply the audience of stories related by Barrie. He was a participant in a creative improvisation that produced Peter Pan, a collaboration that continued into Michaels teenage years and the writing of the later plays.

There have been films, novels, biographies and plays aplenty since Peter first made an appearance in Barries 1902 novel, The Little White Bird, but no perfect accord as to what the poor little half-and-half this half human, half supernatural boy means.

Barries play opened in London in 1904, and played annually to huge audiences for many decades into the future. In America it opened the following year and was just as popular nationwide. In 1911 came Barries Peter and Wendy, the equally famous novel, and in 1924 the first film, a silent movie faithful to the original.

Barrie was surprised by what audiences and critics in America read into the play, particularly about their own history and culture, in which of course Tiger Lily and the American Indians feature more meaningfully than elsewhere. But he could not have wished for more gravitas than he got from Mark Twains note to Peter Pans American star, Maude Adams, that the play was a great and refining and uplifting benefaction to this sordid and money-mad age.

The feeling in America in 1905 was that Peter Pan was a significant symbol of something that society was in danger of losing, even that already we in the West had lost.

But then Walt Disney seized upon the more saccharine elements of the story and produced an animated film which far from censuring our money-mad age turned them to huge commercial advantage.

So pervasive did the Disney interpretation of Peter Pan become in the national consciousness that even today there is for many no incongruity in the eternal boy, the child in all of us, being associated with a pleasure park designed by the singer Michael Jackson, a bus company in Springfield, Massachusetts, a make of peanut butter, and Hummingbird egg candy.

Other animated films followed one from Australia in 1988, and Disneys sequel Return to Neverland in 2002.

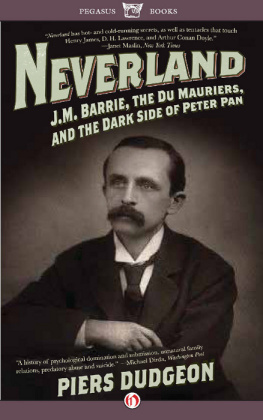

There was however also a different movement, an increasing interest in the life of Peters creator, J. M. Barrie, and of the Llewelyn Davies boys with whose lives Barrie made the play streaky, as he put it.

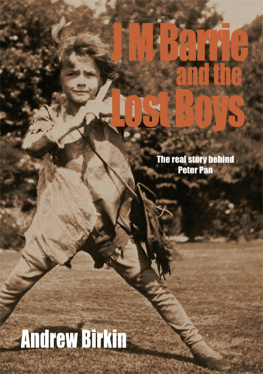

Andrew Birkins brilliant docudrama mini-series, starring Ian Holm as Barrie, led the way in 1978. And Marc Fosters fictional Finding Neverland again featured Barrie in 2004, this time played by Johnny Depp.

But Finding Neverland was not as true to life as it made out. The biographical aspect had been sanitised so that Barrie came upon the Llewelyn Davies family after the boys father had died; thereby removing any possible suggestion that he might have come between Sylvia and her husband.

This phenomenon of writers and makers deftly dampening down or altering facts to idealise Barrie is another pervasive element. Possibly lurking behind it is the fear of the curse levelled at all who would write about him. Even Andrew Birkin admitted to this: I feel somewhat felled by Barries curse May God blast any one who writes a biography of me.

But the curse was not going to stop it happening because there were now two theatres of interest the fantasy story of Peter and the reality of the Davies boys lives. It was only a matter of time before someone noticed that the creative improvisation that led to Peter Pan had not only effected the fiction it had affected the boys who were part of it, deeply.

The first germ of the idea of Peter, long before the original play was written, was a vision of a boy lost in a wood, singing for joy because he knew now that he could be a boy forever and not be compelled to grow into a man.

In the world of film this seemed like the perfect theme for a musical. Dwight Hemions 1976 adaptation of Peter Pan starred Mia Farrow and Danny Kaye. Joseph Weinbergers version appeared in 2001, and in 2014 Phil Willmotts Lost Boy.

Willmotts Lost Boy was interesting not only because it was a musical, but because it reunited some of the characters of the original play as young adults on the eve of the First World War, that great watershed which separated the old world from the new. There is something about Peter Pan that makes him eternally part of the new, with potential for growth and hope for the future.

Meanwhile, the analytical psychology movement had got hold of him and declared Peter a puer aeternus, one of the archetypal ideas that define the primordial, structural elements of the human psyche.

Inevitably there followed attempts to show him at work in the modern world. Damion Dietzs 2003, award-winning Neverland: Never Grow Up, Never Grow Old, was set in an amusement park, with Peter an older, androgynous teenager, and Steven Spielbergs Hook, 1991, presented Robin Williams as a corporate lawyer who discovered the Peter Pan in himself.

Many a production started out with high hopes and ground to a halt before being revived with heavily revised scripts, as if there remained in the minds of their ageing creators an uncertainty of who or what Peter Pan is.

Barrie knew this would be a problem. When it was all over with the boys, he wrote that the tree of knowledge in the wood of make-believe vanishes if you need to look for it. This, of course, is why he had needed Michael.

In search of an anchor in authenticity, every so often a production returns to the Barrie prototype. P. J. Hogans 2003 Peter Pan was faithful to it, but the audience had been led astray so often now that it failed to break even at the box office.

Ten years later Ella Hickson for the Royal Shakespeare Company produced Wendy and Peter Pan. Hickson admitted how difficult it was to convince people that the sentimental, heroic, Disney adventure was not the whole story. She looked hard at the scripts and the book of Peter Pan and noticed how much the theme of death features. With Peter it began with his speculation at the mermaids lagoon, faced with the possibility of drowning, that death would be an awfully big adventure.

In his life with Michael and in two of his later plays A Well-Remembered Voice and the ghostly Mary Rose Barrie became ever more concerned with the question, and the feeling we get is that childhood and death, like two ends of a circle, meet somewhere, and that it is here in this misty arena that the deeply meaningful half of Peter the supernatural half really lies.

It was in this arena that with joy in his heart Michael alone was able to explore the real Peter Pan, and it was here that he met his destiny.

Meanwhile, in 2015, well over 100 years after Peter first appeared, the cinematic and theatrical bandwagon rolls on. Ella Hicksons