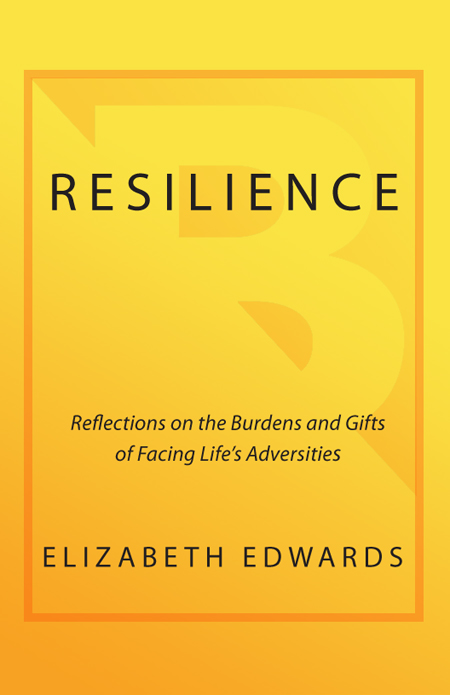

Edwards - Resilience: The New Afterword

Here you can read online Edwards - Resilience: The New Afterword full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2009, publisher: Broadway Books, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Resilience: The New Afterword

- Author:

- Publisher:Broadway Books

- Genre:

- Year:2009

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Resilience: The New Afterword: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Resilience: The New Afterword" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Edwards: author's other books

Who wrote Resilience: The New Afterword? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Resilience: The New Afterword — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Resilience: The New Afterword" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also by Elizabeth Edwards

S AVING G RACES

To my parents,

Vince and Elizabeth Anania

The act of looking forward after a setback is a solitary act, as is writing. But it would be wrong to suggest that no one else played a role. In my case, the looking forward was possibleno, necessarybecause of my children, Cate, Emma Claire, and Jack and the memory of Wade, I acknowledge not only their importance in writing this book but in allowing me the gift of looking forward in life. It is a gift, but also a learned skill, and I learned it from my parents, Vince and Liz Anania, to whom I dedicate this book.

In the writing, I was encouraged and supported by my family, my brother Jay Anania and my sister Nancy Anania, and by my dear friend Glenn Bergenfield.

It may seem obligatory to thank one's editor, but in this case it is accurate. Stacy Creamer was with me through a very difficult time and was supportive of every decision I made about writing, not writing, writing. I cannot imagine a finer, more understanding editor.

1990

stood at the sink in an impossibly bright hospital room washing my face, washing away the heat that, with the doctor's words, had come rushing to my face and neck and chest to fill every pore, to gather in the corners of my eyes and to line my lips and thicken my tongue. He will never walk, his brain is dead, the doctor had said. It still burned. How much cold water would it take to take the hot sting out of those words?

stood at the sink in an impossibly bright hospital room washing my face, washing away the heat that, with the doctor's words, had come rushing to my face and neck and chest to fill every pore, to gather in the corners of my eyes and to line my lips and thicken my tongue. He will never walk, his brain is dead, the doctor had said. It still burned. How much cold water would it take to take the hot sting out of those words?

My father lay immobile behind me, a crisp sheet folded neatly across his chest, the crease apparently to be forever perfect above his forever-still form. I had not been able to bear to see him like that any longer, so I had turned away and instead watched my own warped reflection in the metal mirror that seemed to mimic the distortions within me. The doctor's words were all I could hear inside my head, but they were too immense, too life-changing to stay in my head. They spilled out and filled the room, bouncing back from the walls and the metal me in the mirror, and with every echo a new torment: He will not walk. His brain is dead. He will not walk. His brain is dead. I kept cupping water to my face, unable to cool the heat but equally unable to stop trying.

The day before, this solid man who would be seventy in four days, who still had cannonballs for shoulders and the calf muscles of a twenty-five-year-old fullback, had fallen over while eating a salad for dinner. He had played tennis in the morning and had gone biking in the afternoon. He came in to dinner after planting spring flowers in the yard. Every minute of his day was a test of his body, a test he passed over and over again. And then, with no warning, a massive stroke, and he could not move from the floor. I was forty years old, and I had never seen him fail at a single physical thing he had tried to do. Not once in forty years.

I closed my eyes as I cupped the water, and the images of my well father, strong and full of life, gathered on top of one another. Eating a hot pepper from his garden in Naples and thinking it a green pepper, his face goes flush, tears fill his eyes, his glasses fog up, but he chews on. And then, grinning at his astonished family, he gets up and picks another. The awestruck faces of the enlisted men he commanded in Japan when he came out of the pool into which they had thrown him and, with his soaking wet fight suit clinging to him, they saw his supremely muscled form outlined. News that he had made captain had come in while he was on an early-morning fight, so when he stepped out of the jet in his fight suit, his squadron had rallied around him cheering and had thrown him into the pool in giddy celebration. I always suspected that the vision of him earned him a respect from those enlisted men that morning that the additional stripe on his sleeve would not have won him.

I had sat with him at Bethesda Naval Hospital when he had four discs in his spine fused, the final remedy two decades after his back was injured when the wheels on the jet he was getting ready to pilot collapsed beneath the plane on the tarmac. He should have been groggy and still in the hours after recovery, but he was smiling at everyone, and teasing the nurses by pretending to smoke an endless series of imaginary cigarettes. Within weeks, he was back on his bicycle, and within months, he was back on the tennis court. There was the time his nose was flattened in college in a football game. The doctors said it was so crushed that he could choose whatever shape he wanted since they were starting from scratch. So he chose the shape he had had before. And he took up lacrosse, and he was an all-American his first year. He used to lift women upmy mother and her friendsand twirl them head over heels like batons. Proper women in 1950s shirtwaists ignored the fact that their garter belts had been on display, and they giggled to be treated as girls again. He carried my brother, my sister, and me all at once on his wide shoulders upstairs to bed when we were youngsters as if we were stuffed animals. Now, impossibly, he lay dying behind me, unable to move, unable to speak.

The doctor had called us into the room to tell us. My sister sat with her arm around my mother. My brother sat holding our father's hand. I stood at the foot of the bed, my eyes on my father's still face, not on the doctor I had never seen before. Each of us cried, not in a wailing way, but in low, lonely moans. The doctor talked on about the effect of the stroke on the blood flow to his brain, and we each half-listened, for truthfully nothing after his brain is dead could penetrate. Tracks of silent tears covered all of our cheeks. When the doctor left, we all hugged one another, grieving our collective loss and our individual ones, then everyone else left the room. I had to tell my children, ten-year-old Wade and eight-year-old Cate, where they waited in the hall with their father. And I had to wash my face before I would tell them.

I could clean the tear tracks, but the heat would not go away. I gave up and turned to leave and face the children. As I turned, I looked again at my father, but now he was looking back. He was still immobile, his huge bulk still pinned beneath the tight sheets, but his eyes were open. Not just open but wide dishes of panic. He could not speak. And yet he did. We stood staring at one anotherI haven't any idea how longand he said, or his eyes said, I am here. I am not dead. I am here. I want to live. I answered back in words. Don't worry, I said. We know. We are not giving up on you. And I marched past my family to the nurses' station and told them that that doctor was not allowed back into my father's room under any circumstances.

This was April 18, 1990. We buried my father in April of 2008. Oh, his body kept failing him, little by little until the last of him slipped away eighteen years later. But in between he learned to drive again (in a fairly frightening fashion), and drove until his response time was demonstrably too slow and we could not let him drive any longer. He talked again, in an odd and sometimes inappropriately scatalogical waythe boobs are boilingbut still making people smile, until he no longer could talk easily, and losing confidence in his voice, he started talking again with his eyes. He danced with my mother for nearly a dozen more years. He never biked or played tennis again, but he traveled. He went to Poland and Spain, he took a cruise and watched the whales off the Alaskan coast. He voted for his son-in-law for vice president of the United States. And he was there to bury his oldest grandsonmy first-born. But he was also there to hold four more grandchildrenTy and Louis and Emma Claire and Jackand even two great-grandchildrenAnna and Zacharywho were born after his stroke. In the end, he was surrounded by familyhis wife of nearly sixty years, his children and grandchildren, his sister and her childrenwhen finally, of his own will, he quit fighting and let go.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Resilience: The New Afterword»

Look at similar books to Resilience: The New Afterword. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Resilience: The New Afterword and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.