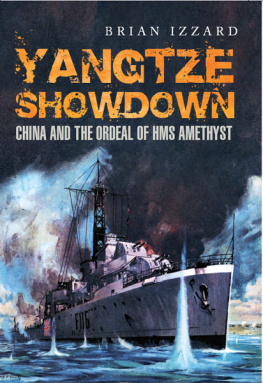

Copyright Brian Izzard 2015

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Seaforth Publishing,

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street,

Barnsley S70 2AS

www.seaforthpublishing.com

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978 1 84832 224 0

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47385 495 6

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47385 501 4

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission

in writing of both the copyright owner and the above publisher.

The right of Brian Izzard to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted

by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset and designed by M.A.T.S. Leigh-on-Sea, Essex

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Contents

For Helen

Authors Note

For style and consistency the following names and spellings have been used: Chingkiang, Chu Teh (general), Formosa, Hankow, Hong Kong, Kwei Yung-ching (admiral), Mao Tse-tung, Nanking, Peking, Yangtze.

Some place names in Admiralty and Foreign Office reports and messages may not correspond to those in current use.

Under Fire

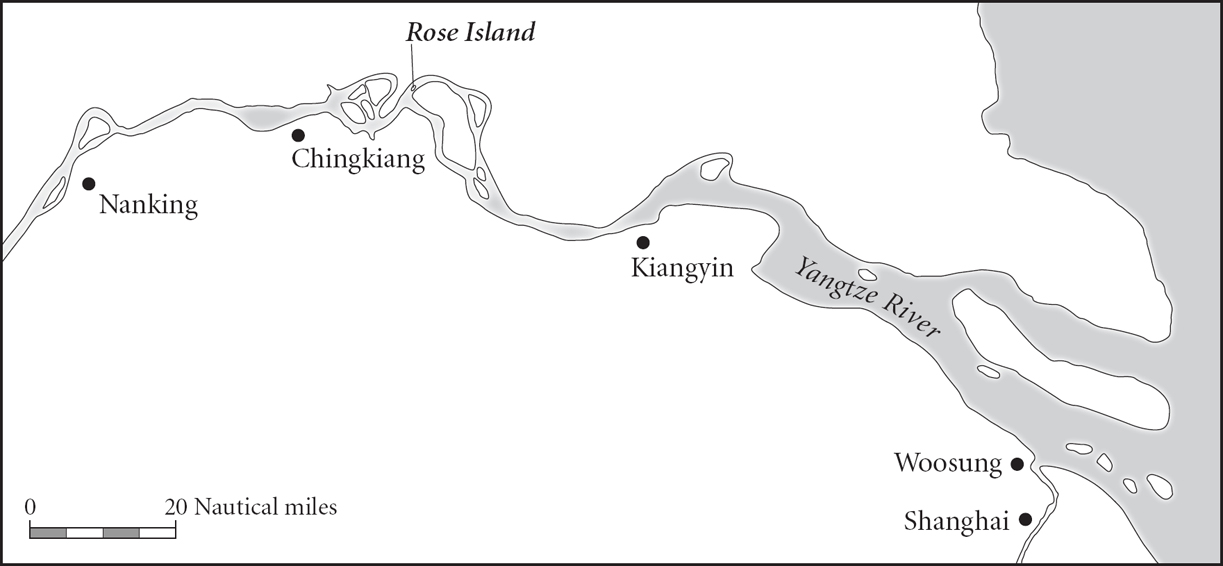

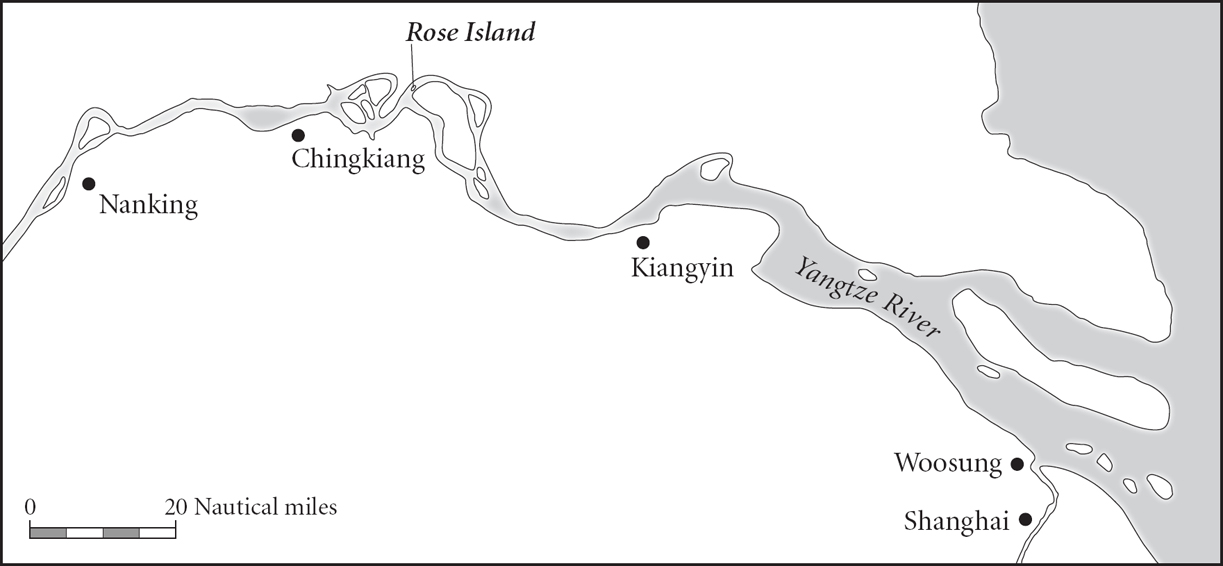

A COUPLE OF SHELLS WHISTLED overhead and a group of sailors on board the frigate HMS Amethyst came to the same conclusion: They couldnt hit a barn door. Amethyst was heading up the mighty Yangtze River from Shanghai to the Nationalist capital of Nanking, where she was due to spend around a month as the guardship for the British embassy. The firing, medium artillery and small arms, was coming from a Communist battery on the north bank, the ships starboard side. Large canvas Union Jacks were unfurled on both sides of Amethysts hull and the firing stopped after about 15 minutes. There were no hits. The ship was at action stations but did not return fire. The main topic of conversation resumed, the run ashore in Shanghai two days previously. Thomas Townsend, a 19-year-old able seaman from a village near Swansea, who was manning an Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun on the port side, said: Wed lowered the Union Jacks, theyd seen it, they knew who we were, theyll be no bother. Later on we discovered they could hit a barn door. The Union Jacks remained over the sides but it was no guarantee that Chinese soldiers who had spent their time fighting on land would recognise them as British, let alone a ship of the Royal Navy on a peaceful mission.

It was the morning of 20 April 1949 and a critical time during the civil war in China. Mao Tse-tungs Communist troops had swept south to strategic areas on the northern banks of the Yangtze and were set to cross the river, aiming to finally crush the forces of the ruling Nationalists. Amethyst was sailing between the two opposing armies. But it was a voyage she should not have taken. At the last moment she replaced an Australian frigate, HMAS Shoalhaven. The Australian government had decided the mission was too dangerous and refused to allow Shoalhaven to sail. The Australians were not the only ones with fears. The US Navy also refused a request from the American ambassador in Nanking to send a warship.

Forty minutes after the first attack there was a huge splash of water forward of Amethysts bow. Communist batteries near Rose Island, about 60 miles from Nanking, had opened up, this time with heavy artillery as well as machine guns. Full speed ahead was rung and the ship moved closer to the southern side of the river to increase the range. On the open bridge the captain, Lieutenant Commander Bernard Skinner, soon realised he was facing a much more serious attack. He shouted, Hoist battle ensigns, and gave the order to return fire.

Amethysts main armament was six 4in guns in three twin turrets, two of them forward and one aft. Stewart Hett, a sub-lieutenant serving in his first ship after training, was at action stations to direct the fire of the main guns. The first few shots didnt hit the ship, said Hett. Up in the director I was told to get on the target. In the director you have two people, ones the gunlayer and ones the trainer who both have binoculars looking at the shore. Im sitting behind them and above them with a pair of binoculars which points in the same direction of the guns so I can see what theyre looking at. We couldnt see where the fire was coming from. It had been foggy and it was still a bit hazy on shore. Eventually we got pointing in the right direction and it was at this stage that we got hit. Three shots hit us almost simultaneously.

The first hit, probably an armour-piercing shell, tore into the wheel-house, fatally wounding a rating and badly injuring the coxswain, Chief Petty Officer Rosslyn Nicholls, who was steering the ship. Nicholls collapsed on the wheel and Amethyst veered to port. The bridge ordered hard a starboard. Leading Seaman Leslie Frank, the only other crewman in the wheelhouse, who was dazed but unhurt, took over.

A shell hit the bridge, killing a sailor and wounding everyone else, Skinner mortally. Donald Redman, a 20-year-old navigators yeoman from Bridgwater, Somerset, who had been standing next to the captain, said:

The shell landed right in the centre. Lieutenant Berger [Peter Berger, the navigating officer] was also caught in the blast and he had most of his clothes blown from him and his underpants were in shreds. The Chinese pilot who was two feet behind me had the back of his head blown off. We were all spattered on the deck.

Years later at a reunion in London Jimmy the One [Geoffrey Weston, the first lieutenant] came up to me and said, Hell, Redman, I thought you were dead. I remember on that day coming up to the bridge, picking you off the skipper, looking at you and saying hes a goner and throwing you on the deck. I said, Thank you very much, sir. He promptly said, No problem, and trotted off to the bar for another brandy.

I was helped from the bridge by someone and taken below. I had large lumps of shrapnel sticking out of me and I was patched up by a shipmate because the sick berth attendant had just been killed. I was able to stand up but I was bleeding rather badly. I thought that if I dont get this stopped Im going to bleed to death. There were lots of wounded. Someone said, What we need is a doctor down here. It was one of the lower mess decks. I said, Ill go and find him. I got on deck and the firing was still going on, ping pong, and the shrapnel was going around. I thought this is a silly thing to have volunteered for. I ran along the deck and found the doctor, who was obviously dead. So I automatically turned around to go where Id come from and as I was passing the galley I was shot in the elbow. I went a little bit further and I was hit by another bit of shrapnel. The first thing I said when I got back to the mess deck was, The doctors dead and if you dont mind I wont go out there again. It drew a little smile from a couple of my mates.

I was then helped down on deck leaning against a bulkhead and they brought a shipmate towards me. He was in a poor state, his tummy had been ripped open. They propped him against me. Someone pulled his stomach together and with my good hand I held it. After about half an hour he died and they pulled him away from me.

Another sailor desperate to find the doctor, Surgeon Lieutenant John Alderton, was Townsend, the Oerlikon gunner on the port side. From my position I never fired a shot, he said.

I had nothing to shoot at. The only bank I could see was the Nationalist bank, and nobody was shooting at me from there. All the firing was coming from the starboard side. Before I knew it, I couldnt believe the carnage. I left my action station there was nothing I could do, so I went to see if I could help anybody. I went round to the starboard side. The Oerlikon there was damaged from a shell burst. The fellow who was on the gun, his throat had been cut from one side to the other. I went down to the boat deck, there were people lying wounded and we tried to ease them as best we could.

Next page