In life, as in art, the beautiful

moves in curves.

EDWARD G. BULWER-LYTTON

A S I REFLECT on the years-long process of writing this book, I keep thinking of George Santayanas observation that the family is one of natures masterpieces. Mine is adaptable, irrepressible, and wonderfully tolerant, and to this clan I owe my deepest gratitude. Special thanks to my lionhearted and stunningly kind husband, John, who spoils me with outpourings of coffee, wine, and love, and to the enchanting, profoundly decent people we have the honor of calling our children: Zeke, Asa, and Annabel.

For her tenacious and cheerful help in hunting down photographs, my sincere thanks to Eddy Palanzo, the Washington Posts prized photo librarian and researcher. I am also deeply grateful to the Posts Richard Aldacushion for his generosity in granting permission to use the photos, and to the gifted photographers whose work I am thrilled to include here. For additional assistance, I gratefully bow to Matthew C. Hanson of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, to Donna Urschel of the Library of Congress, and to Richard Valente.

So many of my current and former Post colleagues have inspired and assisted me, especially my editor, Christine Ledbetter, a class act and one of the most graceful people I know; also the great Henry Allen, friend and guiding spirit, and Michelle Boorstein, Marcus Brauchli, Michael Cavna, John Deiner, Robin Givhan, Peter Kaufman, Ned Martel, Kevin Merida, Chris Richards, and Neely Tucker.

Im grateful to all those I interviewed and mentioned in these pages for their patient answers to endless questions, and to so many others whose insights informed my thinking, including University of Maryland English professor and historian Jane L. Donawerth, sociologists Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson of Columbia University and Cary Gabriel Costello of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, yoga teachers Maria Hamburger and Barbara Benagh, and baroque dance specialist Catherine Turocy, who generously shared her knowledge of European court traditions and body language and what we can learn from them today. For their insights on grace and other wonders, my thanks to Dana Tai Soon Burgess, Alessandra Ferri, Judy Hansen, Tony Powell, Amy Purdy, Xiomara Reyes, and Rebecca Ritzel.

Effusive thanks to my agent, Barney Karpfinger, who believed in this book steadfastly, cheered me on like crazy, and freely bestowed valuable ideas while setting his own example of kindness and grace. I am enormously indebted to the outstanding publishing team at W. W. Norton & Company, and particularly to the exquisitely sensitive editing of Alane Salierno Mason, the gold standard. I could not have dreamed of a more artful, perceptive, or dedicated collaborator. Im grateful also to the amazing designers, and to Remy Cawley, Alice Rha, Jessica R. Friedman for her legal expertise, and Camille Smith and Stephanie Hiebert for their sharp eyes and incisive suggestions in copyediting the manuscript.

Loving thanks beyond words to my parents and heroes, Richard and Catharine, to dearest Dilys, to my brilliant brother David, and to Harvey, a font of calm. Thanks also to Larry, Patricia, Ellen, and to my sister-in-law Sabine, who, at her wedding lo these many years ago, kindly entrusted me (a somewhat shy not-yet-member of her family) with her bouquet as we exited her dressing room, high on M&Ms and hairspray. Her simple gesture of inclusiveness filled me with the flush of gratitude that this book is all about.

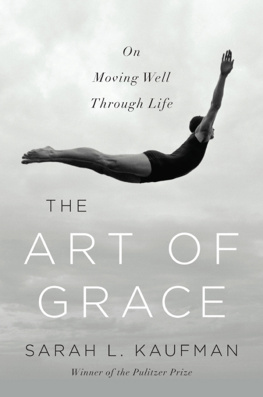

THE ART OF GRACE

TO JOHN, WITH LOVE,

AND

TO ZEKE, ASA, AND ANNABEL,

MY THREE GRACES

The human body is the best picture of the human soul.

LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN

N ORTH BY NORTHWEST, Alfred Hitchcocks sprawling 1959 thriller that takes us to the top of Mount Rushmore by way of a near-miss with a killer crop duster, begins with the basics: a man is walking down a corridor.

But because the man is Cary Grant, the moment is anything but ordinary. He has us at the first step, with that long, brisk stride and its steady rhythm, a ticktock pace that telegraphs purpose, clarity, and efficiency. We watch him stroll out of an elevator toward the street, dictating correspondence to the secretary at his side. Grant plays an advertising executive named Roger Thornhill, and he wordlessly tells us hes a boss with heart. Theres a relaxed, easy give in his body as he moves and as he leans toward his secretary while he speaks to her. Hes so very pleased with his own labors, and yet so exquisitely courteous to his assistant. Hes smooth as whiskey, and getting further under our skin with every move.

In this scene, Grants words are not nearly as important as his movement. Its the movement that hooks us. It always does. Grant tapped into a timeless truth: there is nothing we watch so keenly as the human body in action, because the way it moves tells a story.

A persons way of moving through space speaks to us on a primal level. Its animal to animal, picked up like a scent. Our brains, like those of all mammals, are wired to perceive motion. For most of us, smooth motion is more appealing than jerkiness, especially if the smoothness is variegated, with some unpredictable moments. Think about what your eyes might rest on in the natural world: watching the unperturbed flow of a stream can grow monotonous, while the round, changeable flight of a feather in the wind holds the interest.

Graceful movement is the feather in the wind: smooth but fluctuating. This protean fluidity is a quality that unites all the examples of physical grace to come in these pages. While it may be so subtle that you do not consciously notice it, when an actor, a dancer, an athlete, or anyone else moves smoothly and harmoniouslybut not too smoothly, allowing for surprisesyour eye will follow him anywhere.

The body comes first. Grace is the transference of ease from one body to another. When we witness grace, we feel that ease echo in our own bodies. Graceful people make us feel good.

Grants dark beauty, cultured diction, and gift for comedy are unmistakable. But what I find most fascinating about himand I believe its the reason he is as watchable now as he was all those decades agois his physical grace, his ability to create a flowing performance through physical details. Its not just acting, not just body language, but a movement-infused performance that can be felt as well as seen.

That fluidity is always there, in every role, in the way he walks, the way he slips a hand into his pocket. Its in his comedy and his pratfalls, the way hes never ungainly or clumsy even in well-choreographed moments of panic. (Has anyone ever sprinted through a cornfield with such style?) Its even in the way he stands, and his ability to continue infusing alert physicality into a moment of stillness. He might do this simply through the inclination of his head and the lively focus in his eyes, or by melting his shoulders just a bit toward the costar his character is invariably secretly in love with. He expressed a lot through economical means, which directors, of course, loved.

Grant never wasted a moment on-screen, said Alan J. Pakula (who directed Sophies Choice and All the Presidents Men, among others). Every movement meant something to him.

Next page