Unless otherwise stated, photographs are from the Christine Keeler collection, reproduced by permission of Christine Keeler. Lewis Morley photograph Lewis Morley Archive/National Portrait Gallery.

LEAVES WITHOUT TREES

I WAS DETERMINED THAT NO BRITISH GOVERNMENT SHOULD BE BROUGHT DOWN BY THE ACTION OF TWO TARTS.

Prime Minister Harold Macmillan, 1963

O h, it was a time. High Court judges were performing sexual athletics along The Strand. Government Ministers were spectacularly and inventively at it in the bushes in Hyde Park. And up and down the Thames. With the Archbishops favourite vicars.

If my services dont please you, please whip me, read the card hanging from the bowed neck of a man, nude but for a black leather mask and a white lacy apron, as he served dinner at an aristocratic party. He became The Man in the Mask but he could have been The Man in the Moon for all the accurate guesses at his identity.

Rumour was the trade of the town. There was a miasma of stories: a Cabinet Minister, the son-in-law of Sir Winston Churchill, offered the Government photographs of his penis to prove it wasnt his distinctive organ a high-born lady was dabbling with. Indeed, it was just some Hollywood johnnie and FBI informant who had her devoted attention and string of pearls jangling.

That one was true. Most of the others, the Labour Party kerb-crawling cabal, the cross-dressing Royal, the Horseguards capers, the sex orgies on an island in the Thames, in a multi-storey car park, a homosexual Hellfire Club, a mixed assortment, soft and hard core, of deviant delights, were, perhaps, more inspired suggestions.

Yet, in the first place there had to be something to embellish.

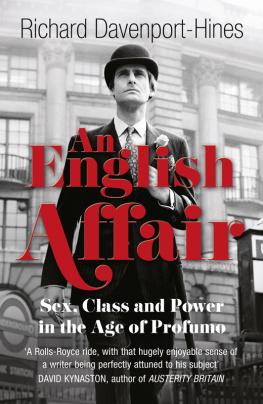

It still seems like yesterday, says Christine Keeler, cocooned in both her clothes and her London apartment, hidden as much as she can from the real and suspected intrusion which has shadowed her for more than fifty years.

Yes, it is more than half a century since The Profumo Affair began, like so much which surprises us, by happenstance. Christine Keeler remains as quick-witted as she always was. Shes wiser, of course, for after a lifetime of being told one thing and sold another she is cautious. Its been like that since she was a toddler. Now, everything in her life is considered before action is taken. Even going out for the cat litter.

Shes been photographed off-guard doing just that and demonised for being without make-up on her dramatic cheekbones and somewhat dishevelled, dressed down in jeans and big woolly jumpers, anoraks and cover-up coats. Its her way of hiding, a camouflage from prurient inquiry. The memorys perception of her is dressed in carefully draped couture Chanel and gloss. She discarded the glamour for the hope of anonymity but long ago accepted that those yesterdays will never be fully erased. Which is why opening up the chapters of her life is again a torment for her. She insists her upset is incidental to getting the story, getting history, accurate. She is someone who was directly involved in world politics at a tumultuous time and about whom so much has been written and said. For decades stories have fluttered around her with nothing solid to ground them, like leaves without trees.

She has always avoided talking in detail about her family, about her difficult upbringing and especially that of her own two sons. Family, where the hurt can usually run, has always been a burden, not a solace. And, ironically, the woman dubbed a sex bomb has not for a long, long time found herself able to have any meaningful emotional or sexual relationship.

So, this book might seem a rueful undertaking. Strangely, its not. There is a great felicity in her attitude today, its as if she can finally cast off all the demons. No one can hurt her now. Nothing can, she says, except distortions of the past which she is about to set straight in the pages which follow.

A great stepping stone in this, a catharsis to the psychobabble lobby, was the death of John Profumo on 9 March 2006, at the age of 91. Christine was offered great financial incentive to talk about him in the days and weeks following his death but never felt it was appropriate. I can understand her reticence: with Profumo gone, she stands alone among the pivotal people, the players who truly mattered, in the sex and politics and vice versa of scandal against which all others have since been sized up.

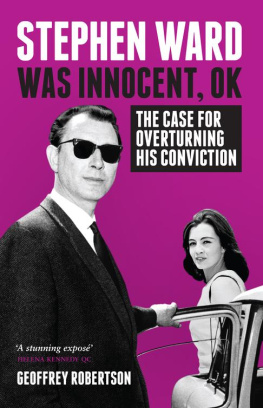

When Profumo died, Christine believed if shed spoken then that this particular piece of history would have been parcelled off, finally put away in a box, by an Establishment which she regards as not having changed much since she and Stephen Ward became victims of it. Ward killed himself in the flat of Noel Howard-Jones who was his close friend and a fondly-loved lover of Christine. Howard-Jones, a man of privilege, was so dismayed at how Britains Establishment treated his friend and justice he left his home country for good. I met him, a most pleasant man, in 2001 when he returned to London from the privacy of abroad to participate with me in a television documentary.

He arrived in the mid-morning, filmed his interviews, shared a pot of coffee and chicken sandwiches, and flew off again that afternoon. If it hadnt been about telling the truth Id never have set foot on British soil again. Im off. He echoed the distaste of many about a still greatly misunderstood period and the people punctuating it. Christine, very much an everlasting part of that cultural curriculum, knows the events as only an intimate possibly can.

Ive worked with her at different times over many years on her story and there is one undoubted thing Ive learned: she will always tell the truth. She says shes never had the time to do otherwise.

Shell correct but she will not retract, she will not compromise, she is emphatic that she will tell it as it is and was, and with no other spin. There is no reward or threat that will make her detour. She is factually fastidious.

Shes clever about modern politics but keeps her thoughts to her very small circle of friends. She loves London and can drive you around avoiding traffic jams and the congestion charge like a Grand Prix veteran. Shes tried living outside the city but its always called her back. Still, even in the capital she enjoys solitude and is comfortable with herself. She has full, busy days and her principle concern is the welfare of abandoned animals. (What would Freud make of that?) She is widely read but almost shy with her opinions.

Shy might seem a strange word for a woman who remains a sexual icon, the pin-up for the anything-goes Swinging Sixties, and whose winning smile and statuesque figure has decorated and brightened not just a chair from Heals but countless history books of the era. Yet, she has to live with her conversation-stopping name. Cary Grant always complained to us that he couldnt escape being Cary Grant for his mind remained that of Archibald Leach. Thats who he was when he was off-duty for his weekend chats. With Christine its similar; shell happily talk away and then suddenly stop surprised at being so outgoing, concerned that what shes said might be misconstrued or repeated to others. She has to be reassured her privacy is safe for thats the one thing she has ferociously clung to like a protective shield.