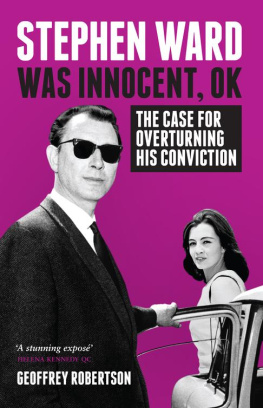

Praise for Stephen Ward Was Innocent, OK

There has been considerable disquiet about the prosecution and conviction of Stephen Ward for half a century. But this is the first time that the critical flaw in the proceedings the perjury of Christine Keeler and its impact on the safety of Wards conviction have been set out with the utter clarity that Geoffrey Robertsons considerable powers of legal analysis bring. Robertson exposes what he describes as an injustice within the law. He sets out a compelling case, with proposed grounds of appeal. This is a must-read for all those concerned to understand how miscarriages of justice can arise.

Keir Starmer QC, former Director of Public Prosecutions

Geoffrey Robertson floods a dark corner of legal history with brilliant light, exposing the lengths to which the Establishment would go to protect the old order and to cover for their own. A stunning expos.

Helena Kennedy QC

Stephen Ward was a scapegoat and a victim both of calumny and a miscarriage of justice, which together drove him to suicide. In this compelling account, beautifully written and argued, Robertson rescues Wards reputation from the lies and legal distortions that condemned him.

A. C. Grayling

A wonderfully clear dissection of a very grim period in British criminal justice. A thriller with a dark ending.

Ken Macdonald QC

In memory of John Mortimer

CONTENTS

T he funeral of Stephen Ward, at Mortlake Cemetery in August 1963, attracted only six mourners and they included his brothers and his solicitor. This distinguished osteopath and skilled portrait artist, a favourite of Londons fashionable society throughout the 1950s, had died by his own hand. At the grave lay a wreath, made up of one hundred white carnations , and a card signed by Kenneth Tynan. It bore the simple inscription

To Stephen Ward,

Victim of Hypocrisy

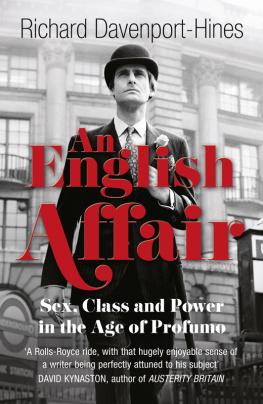

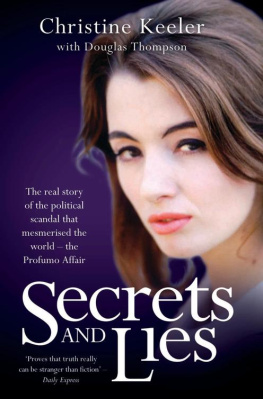

That was true enough. Ward was put on trial at a time of moral panic, when the Christian complacency that had settled over British society after the war had been severely shaken by the Profumo affair. John Profumo, Minister for War in Harold Macmillans Conservative government, had enjoyed a brief affair with Christine Keeler and had lied about it in a personal statement to Parliament. Profumos confession, a few months later, blew the lid off a pressure cooker of rumour and allegation hitherto pent-up by draconian English libel law. Many thought the moral fabric of family life was under real threat from this explosion of sexual scandal , and readily identified Stephen Ward as the cause, both factually (he had introduced Profumo to Keeler, and later exposed Profumos lie to Parliament) and figuratively he was a successful professional with a promiscuous lifestyle and no belief in God. Punishing him, or at least removing him from the society he had apparently corrupted, offered the possibility of propitiation , even regeneration. In the meantime, casualties of the Profumo affair included the flailing Harold Macmillan, who resigned a few months later, and a failing Tory government, narrowly beaten by Harold Wilson in 1964. Contrary to Lord Hailshams pompous prediction, a great party had been brought down by a confessed liar and a woman of easy virtue.

The choice of Stephen Ward for the role of scapegoat was made by Home Secretary Sir Henry Brooke, who summoned the head of MI5 and the Police Commissioner of Scotland Yard and requested them, in effect, to get Ward for any offence he could possibly have committed. MI5 baulked when the Home Secretary suggested an Official Secrets Act prosecution for the very good reason that there was no evidence. The Police Commissioner said there was insufficient evidence for an immoral earnings charge, too, but he volunteered to find some. With unprecedented zeal, the doctors phones were bugged (with the authorisation of Brooke himself), his home and consulting rooms were put under 24-hour surveillance , and his patients were intercepted by police officers as they left his surgery and asked whether they had witnessed anything improper. Dozens of prostitutes were rounded up and pressured to say bad things about Ward; Keeler herself was interviewed twenty-four times in desperate attempts to implicate him in something felonious.

These efforts produced insufficient evidence of any crime, although the police thought them relevant to some seedy-sounding sexual offences relating to pimping (then called poncing) and procuring abortions, and women for other men. Treasury Counsel (barristers who prosecute for the government) rustled up an indictment , and a rubber-stamp magistrate committed him for trial. It took place over seven days in Court No. 1 at the Old Bailey. Outside, crowds booed and hissed and banged their umbrellas on his car. Inside, the court recoiled as the prosecutor denounced him as a thoroughly filthy fellow and an utterly immoral man. The Lord Chief Justice and two fellow appeal judges arranged that evidence which should have secured his acquittal would be hidden from the jury, and his trial judge misdirected them in a way that led to his conviction on counts of which he was palpably innocent.

Stephen Ward appears now as a British Dreyfus a reasonable comparison in the sense that both men were innocent victims of public prejudice and politically expedient prosecutions, although at least the Dreyfus affair involved a serious crime that had actually been committed (by someone else), while Ward was charged with crimes for which there was no evidence that he or anyone else had committed. Dreyfus had his champions at the time, like Victor Hugo, who were able to identify the real culprit and secure the victims release. In Wards case, there were half a dozen books written at the time and half a dozen which have appeared in the half-century since, and all have condemned the prosecution and the trial. They had been written by journalists some, outstanding practitioners of that trade, like Ludovic Kennedy and Phillip Knightley, but with limited knowledge of criminal law and procedure. They exposed behaviour that led to a miscarriage of justice, without fully explaining how and why the professional culture at the time allowed the law to produce such a fraudulent result.

The more I studied the case and talked with older barristers and thought back to my own youthful experiences which began at the Old Bailey a few years later, the more it was possible to read between the lines of the journalists notebooks and court reporters papers. It struck me that the Ward case was an example of what Dr H. V. Evatt, in his analysis of the trial of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, described as injustice within the law (The Tolpuddle Martyrs, Sydney University Press, 2009 edn). He demonstrated how, at a time of moral or political panic (in that case, at the incipient notion of trade unionism), laws and legal procedures could be manipulated to produce an unjust result notwithstanding a seeming compliance with all forensic formalities.

In Wards case, the verdict was reached after manipulation in some respects, disregard of legal rules in force at the time, and through the legal professions lack of consciousness then of what fairness in a trial requires. There are quite a few occasions in the following pages where I comment with relief that this could not happen now. Justice in Britain has improved, as a result of the Irish miscarriages (the Birmingham Six, the Guildford Four etc.) and the work of Chief Justices like Peter Taylor and Tom Bingham to repair the system that produced them. But trial by jury remains vulnerable, especially at times of moral panic. The importance of quashing the conviction of Stephen Ward is not only to right a historic wrong, but to serve as a warning against unfairly investigating and prosecuting scapegoats in order to expiate scandals which are the responsibility of others who cannot be held to account. Public outrage at the sexual marauding of Jimmy Savile and the tabloid misconduct exposed by Leveson has led to massive police enquiries which are bringing many celebrities, journalists and whistleblowers into the Old Bailey dock: they