Pozniak, Kinga.

Nowa Huta: Generations of Change in a Model Socialist Town / Kinga Pozniak.

pages cm. (Pitt Series in Russian and East European Studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8229-6318-9 (paperback: acid-free paper)

1. Nowa Huta (Krakw, Poland)History. 2. Nowa Huta (Krakw, Poland)Social conditions. 3. Krakw (Poland)History. 4. Krakw (Poland)Social conditions. 5. SocialismPolandKrakwHistory. 6. Social changePolandKrakwHistory. 7. MemorySocial aspectsPolandKrakwHistory. 8. Collective memoryPolandKrakwHistory. 9. Intergenerational relationsPolandKrakwHistory. 10. New townsPolandCase studies. I. Title.

DK4727.N69P68 2014

943.8'62dc23 2014036089

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book owes its existence to the time, interest, and generosity of many people on two continents. First of all, this research would not have been possible without the residents of Nowa Huta who graciously shared with me their time and stories. While every Nowa Huta resident I met contributed to shaping this project, a few deserve special mention.

During my stay in Nowa Huta I worked closely with three institutions: the OKN Cultural Center (Orodek Kultury im. C. K. Norwida), the Nowa Huta Museum (Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Krakowa Oddzia Dzieje Nowej Huty), and the Museum of PRL (Muzeum PRL-u). I am grateful to the managers of these organizationsAnna Wiszniewska, Wiesawa Wykurz, and Beata Wako at the OKN Cultural Center; Pawe Jago at the Museum of Nowa Huta; and Jadwiga Emilewicz at the Museum of PRLfor giving me an institutional home base and for facilitating access to both people and research materials.

My life in Nowa Huta became so much more than just a research project thanks to Agata Dudkiewicz, Kasia Danecka-Zapaa, Gosia Hajto, Joanna Kornas-Chmielarz, Barbara Cygan, Agnieszka Smagowicz, Wiktoria Fedorowicz, Marta Kurek-Stokowska, Kasia Nawrot, and Boenka Gurgul. I benefited enormously from the many conversations with Danuta Szymoska and Krystyna Lenczowska, and I am extremely grateful for all their help in procuring materials and contacts. I also want to thank Pawe Derlatka for all the chats in his caf.

In the course of my stay in Poland I was able to reconnect with some family members and to discover new family connections. I thank my grandpa for giving me a home in Krakw; Wujek Jasiu and Ciocia Marysia for the many delicious dinners; Ciocia Lidka, Ola, Gosia, and Marta for the fun-filled evenings; and Ciocia Danusia and Teresa Grzybowska for being my substitute moms.

The Department of Anthropology at the University of Western Ontario was a wonderful place to grow. The intellectual fingerprints of Kim Clark,Marta Dyczok, Randa Farah, Dan Jorgensen, Adriana Premat, and Andrew Walsh are all over these pages, and much of this book was written with their voices in my head. I especially thank Kim Clark for all of her guidance along the way and for all of her advice on academia and on life. Jenn Long was my partner-in-crime throughout all of graduate school.

Different parts of the books argument have previously appeared in the journals City and Society, Focaal: Journal of Global and Historical Anthropology, and Economic Anthropology. A number of photos reproduced in this book belong to the Historical Museum of the City of Krakw, and I am greatly indebted to the museum and its director, Micha Niezabitowski, for allowing me to use this archival material. A special thank you to Pawe Jago for helping to facilitate this process. The maps in this book were created by Anna Lovisa, whom I thank for lending me her graphic design skills.

At the University of Pittsburgh Press, I thank Peter Kracht for his enthusiasm and guidance in bringing this project to fruition, and Alex Wolfe for managing the logistics of it. Two anonymous reviewers provided feedback which helped me sharpen my arguments. I also want to thank members of the Recovering Forgotten History workshop, and especially Marek Wierzbicki, for their comments on the manuscript.

And finally, the most heartfelt thank you goes to my two favorite boys. My son, Jamie, accompanied me on his first trip to Nowa Huta even before he was born. I am grateful to him for turning my life upside down and teaching me what is truly important. My husband, J. J., supported me through every stage of this project and patiently put up with a Skype-based marriage during my fieldwork trips. I thank him for his understanding, for seeing the big picture, and most of all for the life and family that we are building together.

INTRODUCTION

For much of the second half of the twentieth century, the global geopolitical landscape was shaped by two political-economic systems, socialism and capitalism. The two were seen as mutually exclusive and fundamentally incompatible with one another and thus divided the world into two opposing camps. In 1989, this arrangement came to an end as socialist governments across East-Central Europe collapsed one by one. can tell us about the political, economic, and social changes that have taken place over the past quarter of a century.

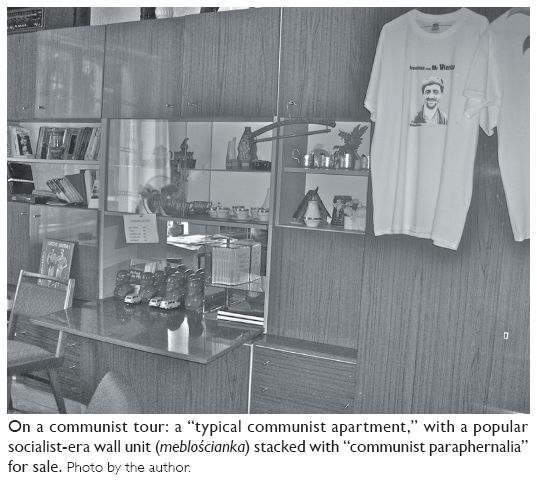

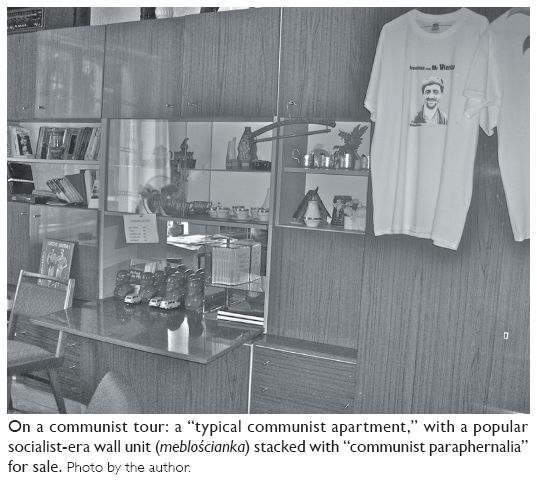

In recent years, socialism has become an object of significant historical curiosity, memory making and contestation (Berdahl 2010, 123) across the region. There is a growing memory industry dedicated to socialism: this includes museums, archives, movies, popular and scholarly literature, and even communist tours, a relatively new form of heritage tourism that has recently emerged in that part of the continent. Let us begin our trip down Polands socialist memory lane by going on such a tour.

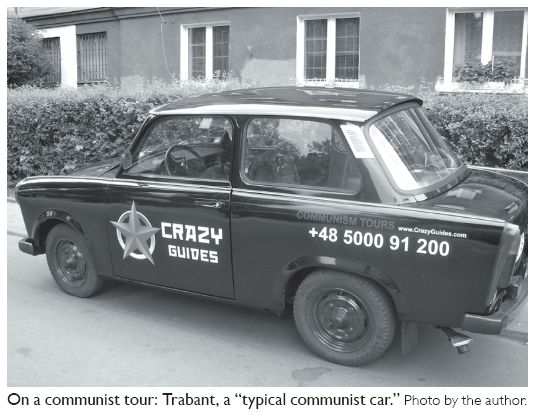

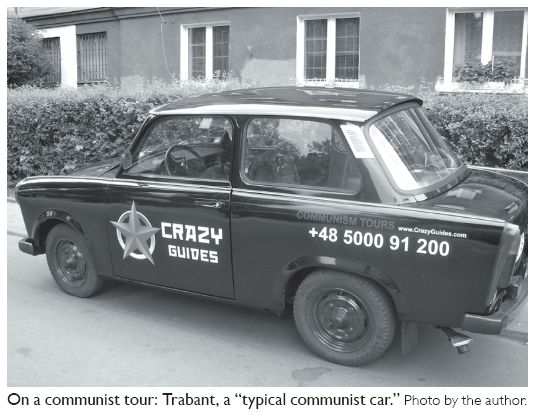

Crazy Guides is a tour company offering communist tours around Nowa Huta, a district of the Polish city of Krakw. Nowa Huta was initially Later on, the guide will pull over on an empty side road on the outskirts of Nowa Huta and allow us to try driving the Trabant for ourselves so that we may experience the thrill of driving a typical communist car that has no power steering.

For now, we arrive in the heart of Nowa Huta. Our first stop is Stylowa (literally, Stylish), Nowa Hutas oldest remaining restaurant, built in 1956. Typical communist restaurant, the guide tells us, and indeed, the dcor seems to reflect the taste of decades past: pillars, marble floors, red tablecloths, clouds of cigarette smoke hanging over our heads. We sit at a table that has not been cleared of dirty plates. Piotrek asks the waitress to clear the table and take our orders, but when she disappears without doing either, he finally does it himself and goes searching for someone who can relieve him of dirty plates and bring us drinks.