BROOKLYN GRANGE

CONTENTS

by Allison Arieff

by Makal Faber Cullen

by Rupal Sanghvi

by Nicola Twilley

by Alissa Walker

INTRODUCTION

I t was a fortuitous miscalculation that led this books photographer, Matthew Benson, and me to drive through Chicago one autumn day and pay a spontaneous visit to the crew at City Farm. We were traveling from Will Allens legendary Growing Power farm in Milwaukee to the urban agriculture mecca that is Detroita road trip far longer than wed bargained forand as we circled Lake Michigan, we agreed wed be remiss in our exploration if we didnt make a stop in a city long recognized as a sustainability leader. With the indispensable assistance of a cell-phone-to-laptop wireless connection, I sat in the passenger seat as we sped south on I-94 and tracked down City Farm manager Andy Rozendaal online. Within a few minutes we were making plans to meet.

The visit to City Farm was inspiring for many reasonsa profusion of vegetables burst forth from neatly designed garden rows, which lie at the base of a strikingly modern single-resident-occupancy building, designed by architect Helmut Jahn, and against a backdrop of the downtown Chicago skyline. Residents of the SRO, many of whom are recovering from substance addiction, take a share of the farms output and even help out from time to time. The day we visited, a trio of kittens roamed the tomato vines, in training to run pest control. On one corner of the property, bees hovered lazily around a stacked hive. We took many great photos and learned all about the history of City Farm, but perhaps the greatest takeaway of the day was Rozendaals response to a question I was asking throughout our travels: What is the difference between an urban garden and an urban farm?

If you wake one morning to dismal weather, Rozendaal told me, and you can stay indoors sipping something warm, watching the sleet or hail pound the soil, and wait for fairer weather before stepping outside, then what you have is a garden. But if your livelihood depends on your crop and you roll out of bed each day and head straight out to your land, rain or shine, then you are the steward of a farm. According to Rozendaal, it is not the size of the plot or the presence of animals, but the need for sustenancenutritional and financialthat makes a farm a farm.

While not every urban farm included in this book represents the sole source of subsistence for the people working there, all of these projects share the philosophy that agriculture can and should sustain a city, whether that means feeding and strengthening struggling communities, catalyzing economic growth and creating job opportunities, improving public health and environmental conditions, or some combination of these.

Like many cities that are now sprouting gardens in place of asphalt, Chicagos modern farmers can trace a rich legacy of practitioners and visionaries who saw agriculture as part of an ideal metropolis. English social theorist and political activist Ebenezer Howard lived in Chicago in the 1870s, two decades before writing one of the seminal works of urban-design thinking, To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform. The book, which was later printed under the title Garden Cities of To-morrow, laid out an integrated city plan that knit swaths of productive farmland and open space into the populated and industrial fabric of the then-modern city.

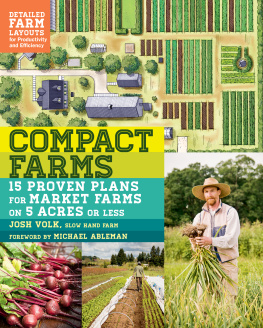

In 1956, architect Frank Lloyd Wright proposed a building for Chicago that would have been the worlds tallest skyscraper, designed to house the population of a small city on a vertical axis, leaving the horizontal plane available for farms. The ground-level portion of his vision was more akin to todays suburbs than to the cities we now know, and the engineering hurdles required to execute his plan rendered it nothing more than a futuristic fantasy. But it was a fantasy that foretold our present moment, when the availability of advanced technology, the growth of urban populations, and concerns over food security and environmental decline are all directing our attention to the promise of introducing agriculture within the city limits.

Urban farming is a uniquely powerful tool for change, in that it can simultaneously reshape the places where we live and the way we eat. It is also uniquely accessibleavailable to grassroots change agents and high-ranking policymakers alike. Just since the beginning of 2010, the launch of Michelle Obamas Lets Move campaign and her White House garden, the presentation of the TED prize to chef and food activist Jamie Oliver, and the release of the FoodNYC report for urban agriculture in New York City all signaled serious intentions to change Americans relationship with food, starting with how and where its produced.

GREENSGROW, PHILADELPHIA

For Obama, Oliver, and the many other leaders and citizens who are now joining the movement, a key step in this process involves getting fresh food into urban neighborhoods where currently none is available. In these so-called food deserts, it is often easier to plant vegetables than to alter the inventory of the mini-marts and liquor stores where many people purchase food or to entice bigger supermarkets to risk opening in low-income neighborhoods.

Agricultural interventions not only facilitate access to healthy food, they become a new social anchor for the community. In New Orleanss Lower Ninth Ward, instead of loitering around the convenience store or playing in the street after school, neighborhood youth gravitate toward Our School at Blair Grocery, a small farm on a formerly neglected corner lot, which has been transformed into a safe haven by an educator named Nat Turner, who relocated from Brooklyn after Hurricane Katrina. Ninth Ward kids can now spend their afternoons feeding chickens, watering sprouts, or simply doing their homework amid the greenery. Blair Grocery farmers even built a small aquaculture structure for raising fisha rich source of protein and an integral part of any traditional New Orleans menu.

VICTORY PROGRAMS ReVISION URBAN FARM, BOSTON

In Detroit, Earthworks Urban Farm extends the services of the Capuchin Soup Kitchen, inviting resource-strapped citizens to grow some of their own food and infusing the soup kitchens daily offerings with fresh, local produce. In a city suffering from economic recession and population decline, Earthworks also acts as a green jobs training ground, preparing people to earn a living as farmers, food distributors, and market employees.

Next page