Table of Contents

Dedication

To my mom, for a love of writing;

my dad, for a love of gardening;

my wife, for a love of life;

and my boys, with great love and hope for a greener future.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to I-5s Andrew DePrisco, who opened the door to the book; to Karen Julian, who ushered it through; and to my two crack editors, Jennifer Calvert and Amy Deputato, who lifted the peaks and filled in the valleys with extraordinary skill and restraint. Id also like to acknowledge the many people who tolerated my ignorance with grace, taught me so much, and shared their enthusiasm for urban agriculture, among them: Martin Bailkey, Rick Bayless, Don Boekelheide, Natalie Brickajlik, Fred Brown, John Cannizzo, Roxanne Christensen, Virginia Clarke, Mary Seton Corboy, Daniel Dermitzel, Wes Duren, Danielle Flood, Lorraine Gibbons, Carole Gordon, Jennie Grant, Mike Hamm, Sherilin Heise, Gregory Horner, Jerry Kaufman, Aley Kent, Erik Knutzen, Michael Levenston, Andrew McCaughan, Michael McConkey, Joe Nasr, Molly Philbin, Robert Philbin, Gordon Prain, Jessica Prentice, Martin Price, Brooke Salvaggio, Wally Satzewich, Bob Scallan, Mike Score, Jill Slater, Jac Smit, Lena Carmen Soileau, and Brenda Tate. It would have been a much poorer book without them, and a much less enjoyable task of writing.

Introduction

When Jac Smitlater to be regarded as urban agricultures chief evangelist, if not its fatherfirst set about writing a book on the topic in 1994, his searches at both the Library of Congress and the library of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations in Rome yielded virtually nothing. It puzzled him. Although he knew the importance of urban agriculture in early history, and had for decades helped to encourage the practice throughout the developing world, urban farming barely registered as a topicmuch less a disciplinein the developed West. He helped to change that, stumping for the development of urban agriculture and co-writing the seminal Urban Agriculture: Food, Jobs and Sustainable Cities with Joe Nasr for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in 1996.

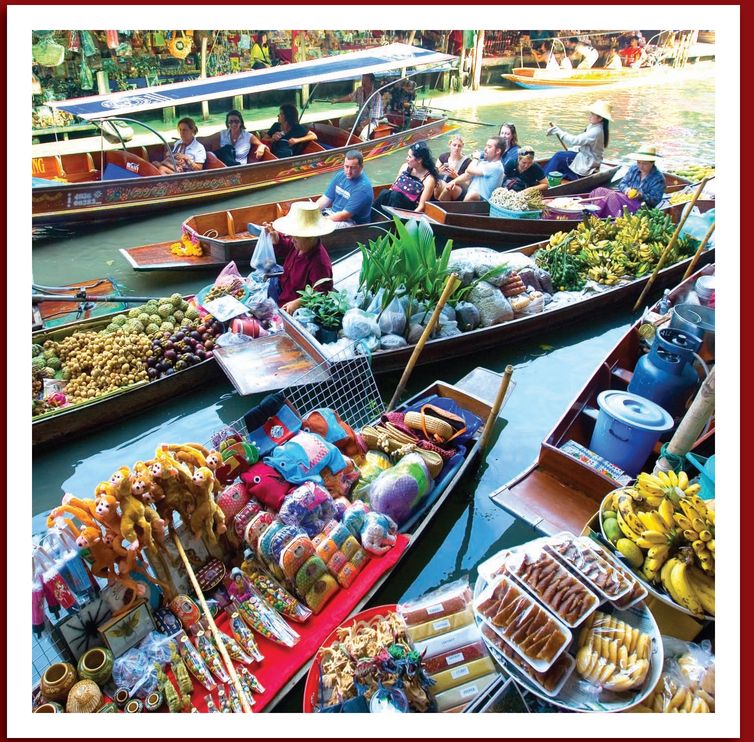

Talk about local color! Beautiful local produce adorns farmers markets across the nation and around the world.

The book proved to be something of a watershed, as evidenced by a quick search on urban farming or urban agriculture in Googles news archive. That search yields just 139 articles published between 1900 and 1995, averaging fewer than two articles for each of those ninety-five years. In the thirteen years from 1996 to 2009, however, such a search finds 3,350 articles, averaging more than 250 annuallyincluding over 800 articles published just during the year I wrote this book. If you live anywhere near a city, you probably dont need Google to have a sense of that. Chances are you will have seen food growing in vacant lots, on balconies and rooftops, along train tracks, under high-tension wires, or in any of the other places where someone can tuck away some plants in cities.

A typical street market in Funchal, Madeira Island (Portugal).

Tomatoes are easily grown in most American cities.

Even as urban agriculture has enjoyed a renaissance in practice and a boom in publicity, it hasnt quite coalesced into a field with a standardized vocabulary and accepted principleswhat prominent researcher Luc Mougeot has called conceptual maturity. This is in part because urban farming fits into so many existing disciplineseconomics, sociology, agronomy, and political science, to name a fewand because the underlying terms are deceptively difficult to define. What makes a settlement urban? Population size or density, a municipal government, public transportation systems, economic activity, universities, or the designation of a government bureau? There are sure to be places most everyone agrees are cities but that fall outside of any of those attempts to define the concept.

This book takes a broad view of cities. Everyone would agree that schoolchildren growing vegetables in a vacant lot in Detroit are engaged in urban farming, so why not schoolchildren on the grounds of their school in Tarpon Springs, Florida, (population: 21,000)? Its not as big, dense, or populous as Detroit, but neither is the city of Tarpon Springs rolling with big open fields. Its a city to the state of Florida, and thats good enough for me.

Ideally, urban farming is agriculture that is (mainly) of the city, by the city, and for the city. This book explores why urban agriculture has begun flourishing since 1996 (chapters 1 and 2), what we may expect of it in the future (chapter 3), and how you can get started on the path to becoming an urban farmer (chapters 49).

A street market in Bali may look different from the farmers market down the street, but theyre all built on the same principles.

Part I:

THE BIG PICTURE

The floating market in Bangkok

Feeding Our Cities

In towns and cities across the globe, in large ways and small, urban farming is quietly gaining momentum. If youre slurping a bowl of hot tom yam goong from a street vendor in Bangkok, enjoying a traditional potato omelet (chips mayai) in Dar-es-Salaam, sipping a glass of merlot in Santiago, or indulging in honey-and-goatcheese ice cream at the Fairmont Waterfront Hotel in Vancouver, chances are you are supporting urban farming. Modern urban farming is closely connected with urbanization, and increasingly with a conscious move toward sustainability. It has even become an unexpected necessity in some places, such as Havana (pictured).

The human population of the world is rising by about 75 million people per yearmostly in citiesand is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050. Sure enough, some of the growth in urban farming happens when towns grow into cities, and cities into megacities, sprawling into once-rural land. Instead of displaced rural farmers working the newly urban landscape, researchers have found most urban farmers to be established city dwellers. It is usually driven in the global north by those looking to reconnect with a sense of place and to live more sustainably, and in the global south by those just looking to live.