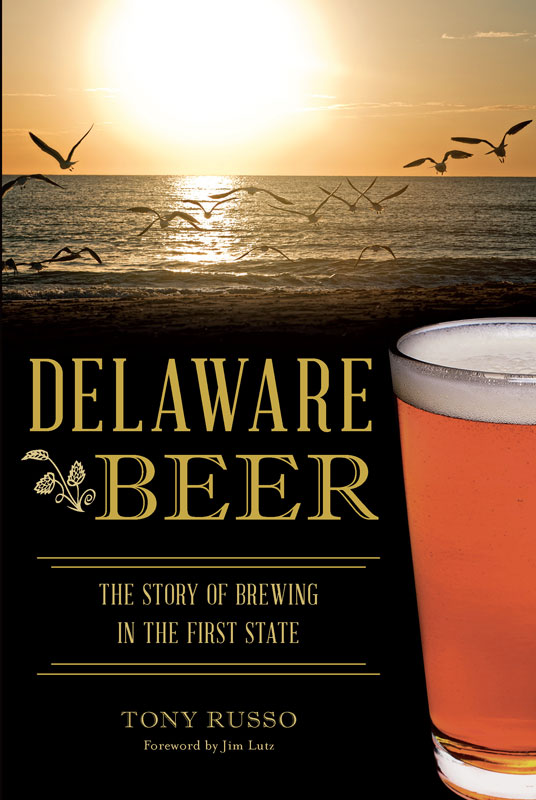

Published by American Palate

A Division of The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Tony Russo

All rights reserved

Images courtesy of Kelly Russo unless otherwise noted.

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.62585.687.6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016930809

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.910.8

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Being born in the Beer Capital of the WorldMilwaukee, Wisconsinand having my Uncle Jack working as a master brewer for Schlitz in the 50s and 60s, you might say that brewing was in my blood. I watched over the years as major breweries closed their doors in the Midwest due to many factors.

When the brewing industry began here in the States, the early brewers needed fresh water to make their lagers. The ability to filter the water at that time was not available, so fresh water was key to making a great lagers or ales. Most towns/cities around the country had their local beer and may have only sold it within one hundred miles from the source.

By the time I was old enough to work in the beer business, I went to work for the Pabst brewing company in its young adult marketing department while in college. I was able to see firsthand what was happening to a lot of these breweries. For many reasons, some of them did not change with the times and had to close their doors in and around the Milwaukee areaPabst, Schlitz and Blatz, just to name a few. This same trend was happening around the country. Local breweries were being replaced by national brands that had figured out how to transport beer from the source in refrigerated railcars and trucks (keeping the beer cool and fresh) to local distributors around the country and then to retail shelves and on draft in bars. These breweries began advertising on national television using sports figures and the like to market their products to the younger (drinking age) generation. Soon the race was on to get that next group of beer drinkers.

Some of the local breweries did not make that change and kept flogging the consumer with the same old stuff. As time passed, these breweries lost market share and were forced to close their doors, and the Big Three got even bigger as these local breweries closed down.

Many years passed and the tide started to change. New brewer pioneers began making products for their local communities, and again the race was on. I remember my first Craft Brewers Conference (CBC) in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, back in the early 90s. It felt like there were fewer than one hundred breweries there to share ideas on how to make, market and sell their products. These brewers shared ideas among themselves to better their products and increase sales and market share. How to get their products to market through distributor networks and then onto the retail shelves and pubs was the big challenge. This is something that was unheard of with the Big Three back in the day. Now when you go to the annual CBC conference, there are more than four thousand breweries there sharing ideas and working together to better the brewing industry.

Like with the early brewing pioneers, these new brewers have a passion for beer and flavor. They also have a passion for their local markets. Many of us only market/sell our beer in a small radius around our breweries, just like our forefathers were doing when they came over to settle here in the United State. Water is not an issue due to filtration, and transportation is not a problem either. Selling our products close to home allows us to connect with our consumer. We open our doors on weekends and allow people to come in to taste our products and see how we are making their beer.

It has been a pleasure to know Tony for years; his passion for good beer and his ability to write about it has helped the growth of the craft beer industry.

JIM LUTZ

Jim Lutz is the president/CEO of Fordham and Dominion Brewing Company. He began his career in 1979 with the Pabst Brewing Company in its young adult marketing department. He made the switch to craft beer in 1985 when he took over as president of Wild Goose in Cambridge, Maryland. His storied rsum also includes a stint at Flying Dog Brewery.

PREFACE

In speaking with Ronnie Price, who had just opened Blue Earl Brewing in Smyrna, I had a bit of a chance to talk about my job. Ronnie had been telling me about how seriously he takes his UnTappd scores. For those of you who dont know, UnTappd is an application that allows beer drinkers to transform themselves into impresarios by scoring beers on a scale of 1 to 5. Before the Internet, the real beer geeks who traveled abroad and to one of the six hundred or so breweries in the country at the time used a notebook to score the beers they tried. They would make detailed notes and had an objective understanding about the term mouthfeel. They used those notes to make themselves better, more intentional beer drinkers, just as a wine aficionado might. I told Ronnie that I never scored a beer worse than a 3 because even though these notes are for me, they are public. Also, if were going to be honest, I am kind of an idiot. I like being part of the culture and taking pictures of myself and my friends enjoying beer. Even though this is my second book on the subject, and I cohost a weekly beer show and produce blogs and articles for free and for pay on the subject every week, Im not a beer writer in the regular sense of the word. I dont write reviews or cover breaking news. I dont brew my own beer, or anyone elses for that matter. I write about culture. From the time I was a student, I supposed that bars, taverns and breweries tell us more about our culture than almost everything else.

What has happened to craft beer since the end of the twentieth century certainly can. This book isnt meant to be a survey of what happened between the time the Dutch landed in Delaware and the time I stopped typing because I was out of time and there were still breweries and brewpubs opening daily. Instead, it is my attempt to tie together the way that people do beer with the whys about its success and meaning. The whos pretty much take care of themselves. What is in the book will, with any luck, be revealed in the chapters that follow, so its probably easier to tell you what isnt. Ill start with the work of two other authors: John Medkeff Jr., whom Ill mention again in the first chapter (for the dizzying number of people who read a book but skip the preface) and Sam Calagione.

In Delaware Brewing, John covered the history of Delaware beer in a way I couldnt. It is a fair and accurate history that wrings the colonial and industrial history out of sources in a way that I frankly dont here. At this writing, I havent met John, but in going through the archives in Wilmington, I could see his fingerprints clearly still. I was unable to uncover anything he didnt (except maybe a letter ordering up a Swedish wife who could brew), so I operated under the assumption that people dying for those details are better served by him. If you page through the first chapter unsatisfied, his book has more details.

Next page