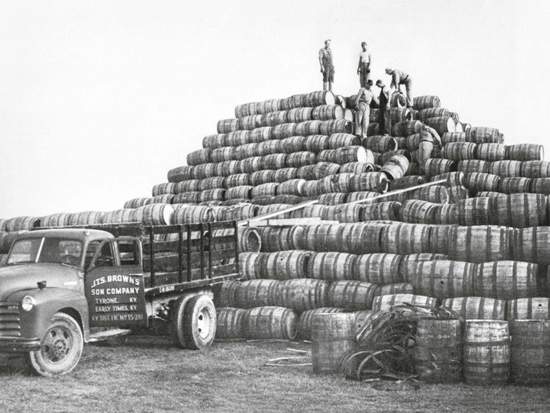

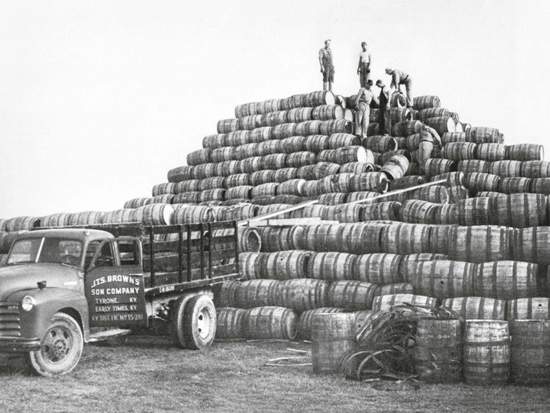

Stacking empty barrels at the J.T.S. Brown distillery (now Wild Turkey)

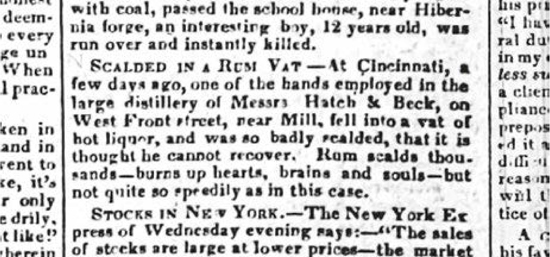

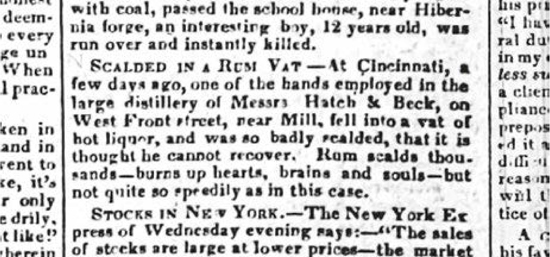

Distillery Hand

BALTIMORE SUN

MAY 22, 1846

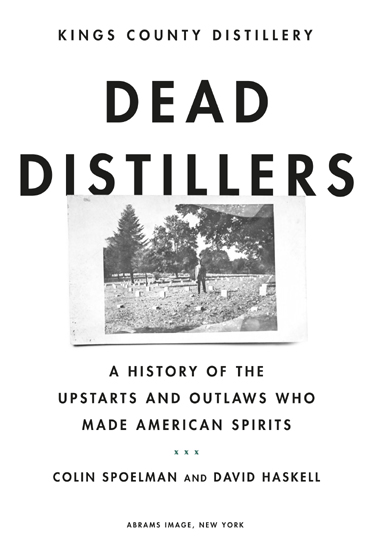

INTRODUCTION

I have become a connoisseur of cemeteries. Bardstown, Kentucky, has two. The good one is near the Old Talbott Tavern. Its jagged stones (the ones that still exist) stick out at odd angles, the grass is not regularly mown, and there are no fences to separate the burying ground from people parking for a quick stop at the bank or to walk the dog. The cemetery can be visited in a minute or two; theres not much left to see but the ancient markers, a small bit of evidence in this little town of life in the eighteenth century. If there are any distillers here, they are likely forgotten.

Most of the known distillers are up the street, at the city cemetery, which is divided into a Protestant and a Catholic section. Jim Beam is buried here, but so are the founders of Makers Mark and Willett, as well as other, forgotten distilleries, long closed. The city cemetery is more conventional, almost suburban: a wooden gazebo, some long straight avenues that keep an orderly rectilinear plan, very few trees. The only thing unusual about it is the peculiar, persistent smell of bourbon mash, which drifts over from the Barton distillery, half a mile away.

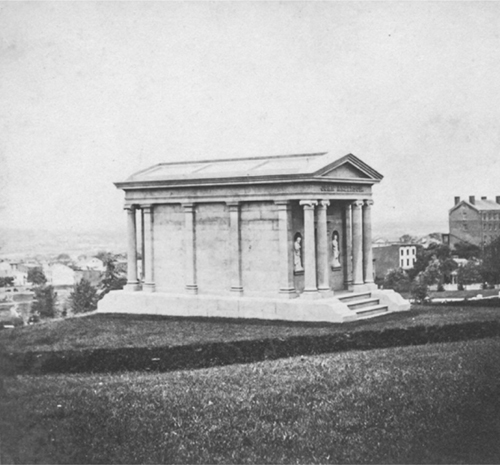

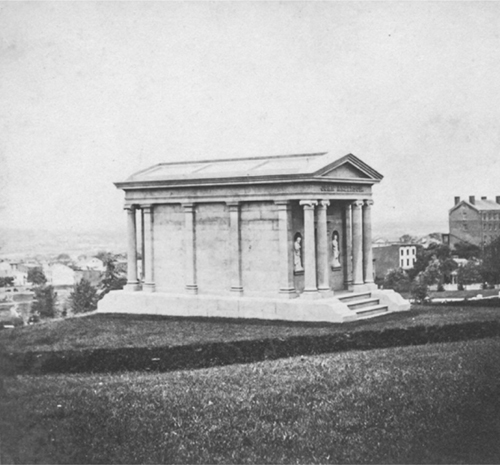

Green-Wood in Brooklyn, dark and overgrown, has a surprising share of distillers. With its grand monuments covered in lichen and soot, showing the wear of proximity to the city, it would take weeks to walk the curving lanes and paths throughout the grounds 478 acres. Cave Hill in Louisville is cleaner but less grand; its burial markers elegant but less numerous. Spring Grove in Cincinnati has singular large monuments that are spread out like follies in a large gothic garden. The national cemetery in Arlington is a pastoral theme park, with hordes of tourists and school groups wandering in noisy clusters through the ordered grid of government-issue stones. When visiting the grave of Leonard John Rose in Boyle Heights, in Los Angeles, I saw an entire family tailgating at a headstone, a celebratory affair as best I could see from a respectful distance, and a spark of humanity in an otherwise sterile park of grass and stone.

David and I became interested in cemeteries when, in 2011, an employee at Brooklyns Green-Wood, the first planned cemetery in New York, came up with the idea for a somewhat unconventional tour: a visit to the graves of former distillers, followed by a whiskey tasting at one of the craft distilleries that had recently established themselves in the borough. In the 1840s, New York made as much as 25 percent of the distilled spirits consumed in the country, but that history is largely unknown to current New Yorkers, as distilleries gradually moved south and west, until the political forces around the temperance movement killed the last one some time after 1917. Then, thanks to changes in state laws, a wave of craft distilleries returned to the city. Kings County Distillery, established in 2010, became the first in the city since Prohibition. As distillers particularly interested in this forgotten history, we jumped at the chance.

This tour of dead distillers proved to be strangely intriguing, more than a stunt to attract morbid neighbors or an excuse to drink in the afternoon. There was something humbling to be surrounded by so many distillers in a city that had abandoned the vocation completely for a hundred years. The immersion in death and quietude had a disjunctive effectreassuring as much as frightening; somehow the cemetery conveyed both a sense of optimism and pessimism. The cemetery felt like a place of great mystery and possibility, a kind of catalog of stories, lost to time.

Exhuming some of the stories of those we visited on the Green-Wood tourand viewing them in the context of graves and eternityled to some revelations about our own chosen profession. There is something allegorical about distillers, liquor, and death. Here, we tried to extract from the stories of individual distillers a distinctly American story (and morality tale), though it is a story without an ending and with a preponderance of subplots. Like the cemetery itself, it is a collection of characters, oddly juxtaposed, arranged more or less chronologically by death date.

Green-Wood Cemetery

This is a book, then, about distillers who have died. Some are well known, either because their names can readily be found on bottles on liquor store shelves or because the alcohol they made was a footnote to an otherwise memorable life. Others remain nameless, known only to history by an account of their accidental death, written in small-town newspapers at a time when every city was a town and when distillery accidents were common tragedies, as much the stuff of morning papers as the price of vanilla beans, hemp rope, or saltpeter. This book takes a broad view of who can be considered a distillera factory hand, a business owner, a salesman, a slave.

Americans have been distilling for almost four hundred years, starting with Dutch businessmen Cornelis Melyn and Willem Kieft, who built the first commercial distillery on Staten Island as an adjunct to a plantation. Jim Beam and Jack Daniel were distillers, of course, but so were presidents George Washington and Andrew Jackson. Industrialists Andrew Mellon and Henry Clay Frick were distillers, but so was Birdie Brown, who lived under the Judith Mountains in Montana and, in 1933, blew herself up while making moonshine as she was dry cleaning. Because alcohol has such a contentious place in North American history, our distillers are heroes or villains, existing uneasily in that space between honest businesspeople and merchants of depravity.

Though disparate in historical and geographical circumstance, these distillers often share common traits: humble beginnings, fierce industriousness, ostracism from prevailing society, personal reinvention, a propensity for exaggeration, a contrarian spirit, indomitable energy, superstition, social insecurity, a surprisingly common affinity for fast horses.

The act of distilling remains more or less the same today as it did in the 1600s, when it first appeared on the North American continent. The technology has not advanced substantively, and while the product has experienced eras of boom and bust, we continue to drink hard liquor in roughly the same quantity as our parents and great-great-grandparents. Because spirits are so often aged, the distillers art remains a long game, won only after years of toil, and, indeed, sometimes it takes many generations for children to reap the rewards set in motion by their forefathers.

And because the product of distillationthat is, hard alcoholhas often been looked at derisively by the American moral elite, the distiller has often worked in the shadows or at the margins of society. Though federal prohibition against alcohol enacted in 1920 collapsed after only thirteen years, the temperance movement has been a narrative through-line in this countrys history, even to the present day. It has been our conscience, scolding us for trying to buy our joy through drunkenness, holding out for the clearheaded America that we have always believed we want to be, a society of ideas.

Next page