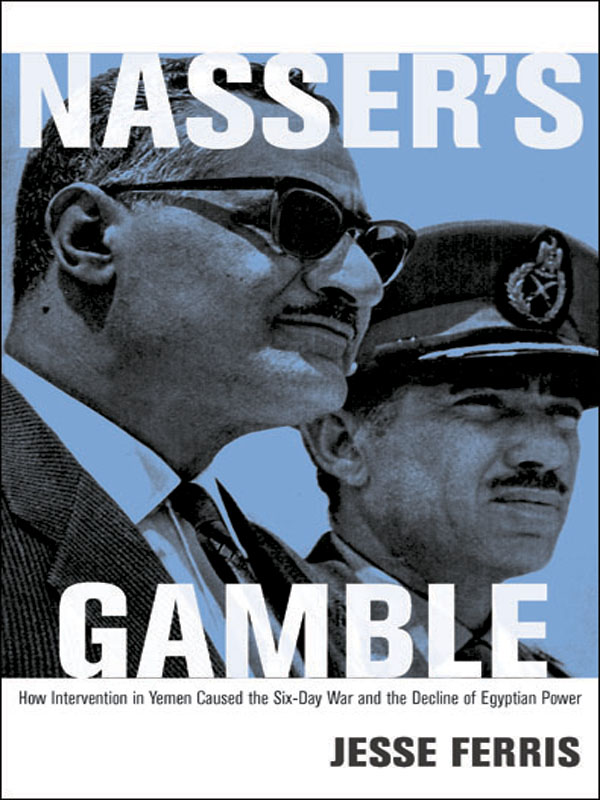

Nassers Gamble

Nassers Gamble

HOW INTERVENTION IN YEMEN CAUSED THE SIX-DAY WAR AND THE DECLINE OF EGYPTIAN POWER

JESSE FERRIS

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2013 by Princeton University Press Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket Photograph: Abdul Nasser Meets the Yemeni People. from al-Quwwat al-Musallahah, Egyptian weekly journal, supplement to volume 412, May 1, 1964. Courtesy of The Arabic Press Archive, Moshe Dayan Center, Tel Aviv University Israel.

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ferris, Jesse, 1972Nassers gamble : how intervention in Yemen caused the Six-Day War and the decline of Egyptian power / Jesse Ferris.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15514-2 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. EgyptForeign relations19521970. 2. EgyptMilitary policyHistory20th century. 3. Nasser, Gamal Abdel, 19181970. 4. Yemen, NorthHistoryRevolution, 1962Participation, Egyptian. 5. Yemen (Republic)History19621972. 6. Israel-Arab War, 1967Egypt. I. Title.

DT107.83.F47 2013

956.046dc23 2012028784

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Palatino

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

The Road to War

CHAPTER TWO

The Soviet-Egyptian Intervention in Yemen

CHAPTER THREE

Food for Peace: The Breakdown of US-Egyptian Relations, 196265

CHAPTER FOUR

Guns for Cotton: The Unraveling of Soviet-Egyptian Relations, 196466

CHAPTER FIVE

On the Battlefield in Yemenand in Egypt

CHAPTER SIX

The Fruitless Quest for Peace: Saudi-Egyptian Negotiations, 196466

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Six-Day War and the End of the Intervention in Yemen

AFTERWORD

The Twilight of Egyptian Power

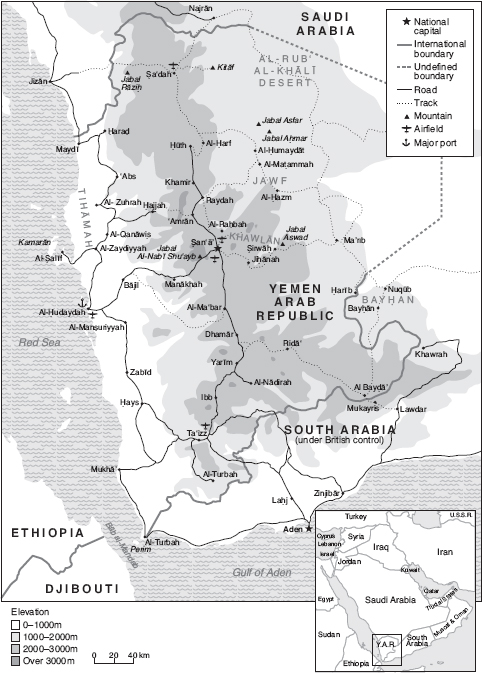

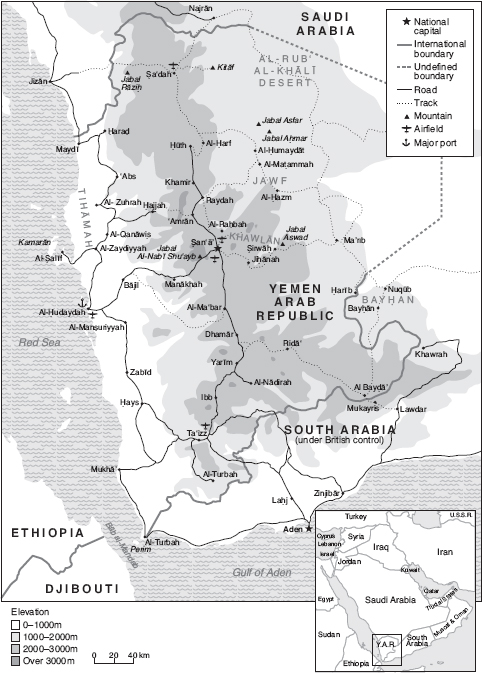

Map of Yemen ca. 1965.

Acknowledgments

THE OPENING LINES of a first book afford a singular opportunity to pay tribute to those who have shaped ones growth as a scholar. My intellectual story begins with Donald Kagan, who taught me all about foxes. The late Bill Odom then tried to get me into hedgehogs. Michael Doran guided me into the labyrinth of Middle Eastern politicsand suggested that I look at Yemen and take Russian. I went to Stephen Kotkin seeking perspective on Russia and came away with a new approach to history.

Many other distinguished colleagues and friends have helped shape this book. kr Haniolu, who has been unstinting in his support, read several drafts and provided many helpful comments; so did Bernard Haykel, who shared his private library with me. Elie Podeh contributed expertise in Arab politics and valuable counsel along the way. Bernard Lewis furnished invaluable references and encouragement. L. Carl Brown read through the entire manuscript and provided many insightful comments. Mark Kramer and the editorial staff at the Journal of Cold War Studies helped refine the ideas contained in the second and fourth chapters. Michael Oren provided helpful advice and support at key junctures. Oscar Sanchez generously shared the results of his research. David Freedel, the best language instructor I have ever known, taught me Russian. The noble-hearted Musa Odeh transformed my Arabic. Gali Dagan, a true friend, endured many hours of conversation about Yemen. Vladimir Shubin, Alexei Vassiliev, Oleg Peresypkin, Constantine Truevtsev, Zaid al-Wazir, Qassim al-Wazir, and many others shared their reminiscences. Desmond Lachman and Yotam Margalit contributed economic expertise. Rachel Green and Maayan Ravitz-Shalom jealously guarded my time. Ira Bein, Frank Grelka, Shaul Levy, Rami Livni, and Baker al-Majali assisted with research. Shane Kelley designed the maps. David Luljak prepared the index. Hanna Siurua afforded help with transliteration. David Altshuler, Richard Boylan, Gabrielle Chomentowski, Yoav Di-Capua, the late Haim Gal, Yuri Gershtein, Arch Getty, Ami Gluska, Regina Greenwell, Lorenz Luthi, Vitaly Naumkin, Michael Reynolds, Yaacov Roi, Eran Shalev, Anita Shapira, Reg Shrader, Uriel Simonsohn, Tawfiq Uthman, Alan Verskin, Tsering Wangyal, and Salim Yaqub all helped in various ways. I am deeply indebted to Daniel Stolz, whose thoughtful diligence made it possible to turn a rough draft into a complete manuscript in relatively short order.

I owe a special thanks to Brigitta van Rheinberg for shepherding this project deftly through to a swift conclusion. Larissa Klein, Leslie Grundfest, Dawn Hall, Dmitri Karetnikov, and the dedicated staff of Princeton University Press helped make the birth of this book a surprisingly painless experience. This project would not have been possible without the generous support of the Israel Democracy Institute, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Donald and Mary Hyde Fellowship Fund, the Kennan Institute, the Social Science Research Council, the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, and the Departments of Near Eastern and Judaic Studies at Princeton University. I am indebted to the staff of the Arabic Press Archive at the Dayan Center at Tel Aviv University, whence come most of the images. I am especially grateful to Arye Carmon for drawing me into the extraordinary institution he has built and for providing such a stimulating environment for the completion of this project.

I owe so much to my parentsnot only for their love but also for their discipline; to my sister, for her understanding; to Noah and Eli, for inspiring love beyond words; and especially to Kathryn, who lured me all the way from Latin class in college to an accidental PhD. This book is dedicated to Susan, whose DNA is inscribed in every line.

Introduction

A LOW-RESOLUTION PHOTOGRAPH of Egypts international position around 1960 would have looked something like this: For the first time in centuries, perhaps millennia, Egypt was completely free of foreign domination. The great powers of the East and of the West competed against each other to arm Egypts military, build its industry, and feed its people. Egyptian power extended deep into the Levant, further than at any time since Muhammad Ali. Egypts charismatic president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, was the undisputed leader of the Arab world. Peace reigned, thanks to an astute leaderships assiduous avoidance of war.

A second snapshot taken a decade later would have revealed a dramatically different picture: Following the secession of Syria in 1961 and Israels conquest of the Sinai Peninsula in 1967, the territory under Egypts effective control had shrunk by 20 percent. Nassers reputation was in tatters, shredded by serial setbacks at home and abroad. Egypts economy lay in debt-ridden ruin, its future dependent on Saudi largesse. Ties with the United States had disintegrated. And the defense of the realm from Israeli attack relied on a Soviet division in quasi-occupation of the Nile Valley.

Next page