Bloomsbury USA

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

| 1385 Broadway | 50 Bedford Square |

| New York | London |

| NY 10018 | WC1B 3DP |

| USA | UK |

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2018 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

First published in Great Britain by Goodman 2017

First U.S. edition published by Bloomsbury 2018

Text Ogilvy & Mather, 2017

Design Carlton Books Ltd., 2017

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

ISBN: 978-1-6355-7146-2 (HB)

ISBN: 978-1-6355-7147-9 (eBook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletter.

Bloomsbury books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases please contact Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at .

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

VIEW FROM TOUFFOU

Unlike authors who have to worry about why they are writing at all, my purpose is very narrow. The point of this book is to persuade people to read or re-read Ogilvy on Advertising by David Ogilvy. It is still pure, pure gold. Yes, the cast has changed, the scenery is different, the plumbing is new, but the tragic and comic plots, sub-plots and counter-plots of this business remain persistently and defiantly unchanged. Of course, this irritates some people who really would rather all had changed completely.

I am writing these words in Touffou, the home David retired to in South West France, in the room he used as his study. The desk on which Ogilvy on Advertising was partly written is still here, although in a different room. The shelves in the study contain a range of books, which testify to his belief that the most productive people read the most widely. Theres history, biography, architecture, travel spines with titles that sum up a mans life. And, of course, there are the advertising books.

Touffou evolved over several centuries, but the original keep, built for defence, dates from the twelfth century.

The house nestles between some low wooded elevations and the banks of the River Vienne as it winds lazily through the countryside of Poitou. David settled here in 1973 with his third wife, Herta. The couple spent the next decades restoring Touffou, turning the grounds into a magnificent garden and creating a grand but friendly home.

David and Herta in San Francisco, 1984.

David died here in 1999, and his ashes are scattered in the garden. Herta remains Ogilvy & Mathers materfamilias; and we continue to hold Board meetings, Executive Committee meetings, client meetings and workshops here.

In 2013, I called our Digital Council to Touffou. This was a group of young enthusiasts from around the world and from around the eco-system mobile, customer relationship management (CRM), social, creative, technology. Our previous meetings had taken place in Palo Alto, CA, but there did not seem anything incongruous in talking about the future of communication in a medieval setting. In fact, it gave us something that we simply could not so easily get in California: perspective. Well into Ogilvy & Mathers own digital transformation, I wanted a discussion of a more fundamental kind. What is digital? Is it an evolution or a revolution? Is it so novel and specialized that we should treat it apart? Or it is something that needs to be baked into the heart of the business, an integrator in itself? We had guidance, in part, from a videotaped last testament that David left. He called it View from Touffou. We still play it in training sessions. It makes a point about press advertising, but one that helped us answer the questions.

Davids View from Touffou video provides a posthumous take on digital. He would have viewed digital as a channel not as a discipline, one that cries out for rich content, and always in the service of selling.

His argument provided a flash of illumination, bringing into high relief the primacy of content over form. The meeting continued along a path divergent from the one being followed by so many others. It led us to see digital not as a discipline but rather as just a channel, a dramatic enhancer of traditional business, but not a parallel universe.

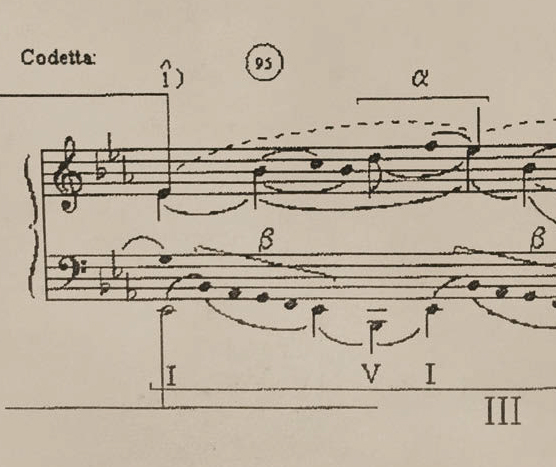

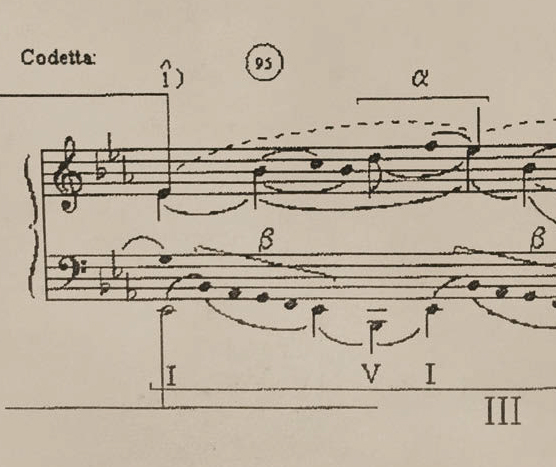

CODETTA

A codetta is what ends a musical sequence.

Ogilvy on Advertising begins with a chapter called Overture. It is classic David Ogilvy. Plainspoken, forthright and resonant with his concise prose, it includes his famous line: I hate rules.

The book is a simple yet demonstrative expression of Davids breadth of knowledge, containing illustrative references to, among other things, eighteenth-century obstetrics and Horace. And it sparkles with his wit and good humour, ending with this note: If you think it is a lousy book, you should have seen it before my partner Joel Raphaelson did his best to delouse it. Bless you, Joel.

A codetta, or little tail in its native Italian, is a brief conclusion in music. It leads back into an exposition or recapitulation of the work before, or occasionally, to a section that develops the piece further. My codetta does the latter building on Davids book by adding some fresh notes on the nuances of the digital age.

My codetta rounds off what David began, though it will not be the last word.

Ogilvy on Advertising was written in the 1980s. Joel, Davids literary amanuensis, recalls the speed with which it was produced: David posted a chapter to Joel every week. Joel was on sabbatical in Colorado, but his job was to edit it and make suggestions. Written partly in Touffou, at Davids desk in his study, and partly in a chalet in Switzerland, it is a polemic.

David did not think it was his best book, and he was right. Confessions of an Advertising Man (1963) deserves that appellation. It is more literary: while many copywriters have found it difficult to extend short form into book form, David had a natural gift for book writing.