His argument provided a flash of illumination, bringing into high relief the primacy of content over form. The meeting continued along a path divergent from the one being followed by so many others. It led us to see digital not as a discipline but rather as just a channel, a dramatic enhancer of traditional business, but not a parallel universe.

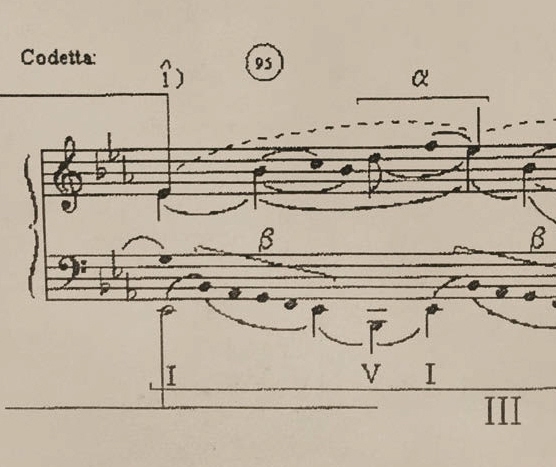

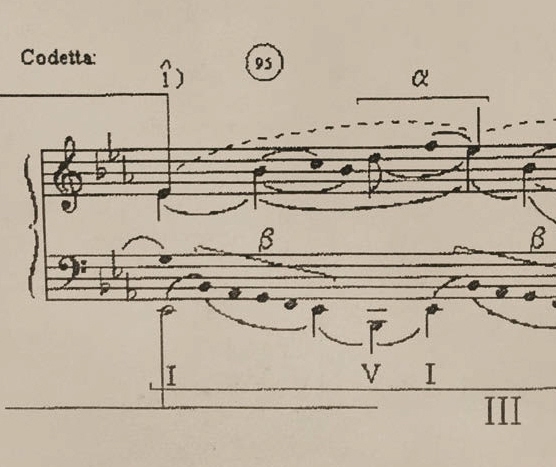

A codetta is what ends a musical sequence.

The book is a simple yet demonstrative expression of Davids breadth of knowledge, containing illustrative references to, among other things, eighteenth-century obstetrics and Horace. And it sparkles with his wit and good humour, ending with this note: If you think it is a lousy book, you should have seen it before my partner Joel Raphaelson did his best to delouse it. Bless you, Joel.

A codetta, or little tail in its native Italian, is a brief conclusion in music. It leads back into an exposition or recapitulation of the work before, or occasionally, to a section that develops the piece further. My codetta does the latter building on Davids book by adding some fresh notes on the nuances of the digital age.

My codetta rounds off what David began, though it will not be the last word.

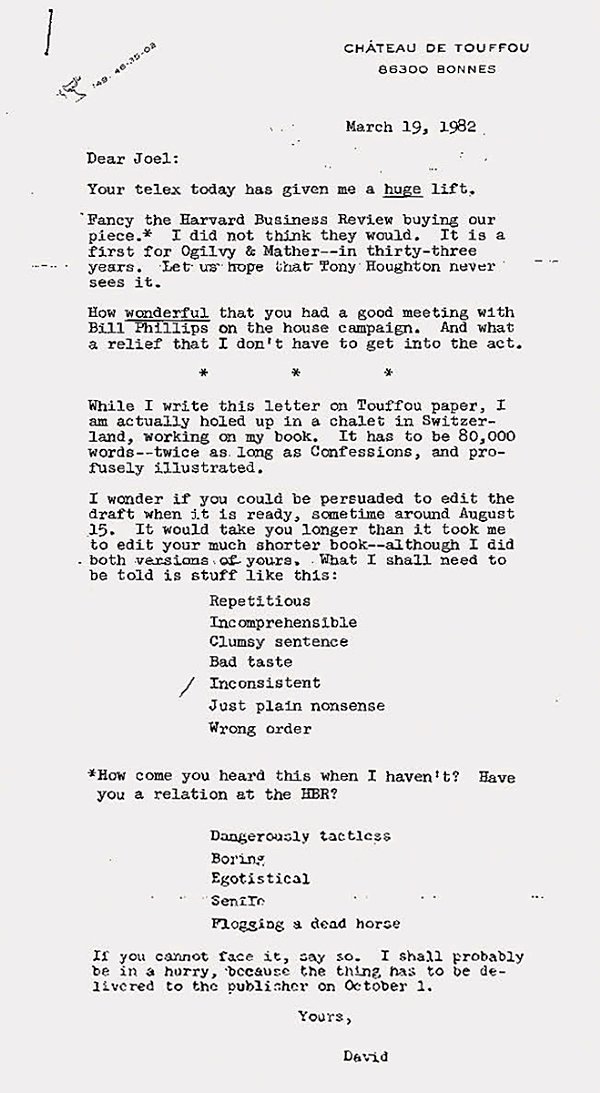

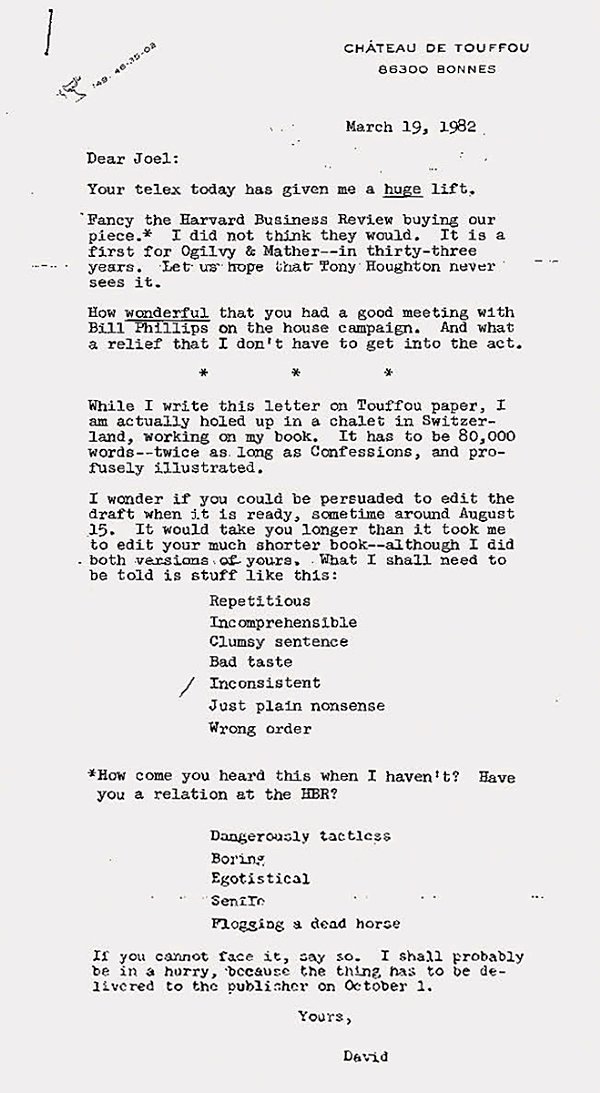

Ogilvy on Advertising was written in the 1980s. Joel, Davids literary amanuensis, recalls the speed with which it was produced: David posted a chapter to Joel every week. Joel was on sabbatical in Colorado, but his job was to edit it and make suggestions. Written partly in Touffou, at Davids desk in his study, and partly in a chalet in Switzerland, it is a polemic.

David did not think it was his best book, and he was right. Confessions of an Advertising Man (1963) deserves that appellation. It is more literary: while many copywriters have found it difficult to extend short form into book form, David had a natural gift for book writing.

But Ogilvy on Advertising was something else: a most elegant rant against what he believed to be a legion of misconceptions about our business; a primer for anyone interested in advertising; an expression of some very dogmatic views, skillfully excused as brevity; and a showcase for the work he admired most (including a sizeable chunk of his own oeuvre).

Within months of publication, Ogilvy on Advertising was a storming success. It has become an advertising classic, remaining in print for over three decades, translated into multiple languages, and featured in legions of syllabi around the world. More than that, many people I meet, whether theyre in the industry or not, tell me that the book is the first or only point of contact they have had with the agency he founded.

I first met David in 1982, as a young Account Director in our London advertising agency. I was working in my small office there in the early evening. He happened to walk past, saw there was someone new inside, retraced his steps, came in and flopped in a chair. Who are you? Then, What are you doing? I was full of our recent win of the Guinness business, what wonderful work we were doing. He just looked at me and asked: But are they gentlemen? Some months later, their CEO, Ernest Saunders, fell like Lucifer. David had a prescience that was often uncanny.

David produced the original manuscript for Ogilvy on Advertising with characteristic efficiency, sharing a chapter every week with his friend and literary confidante, Joel Raphaelson.