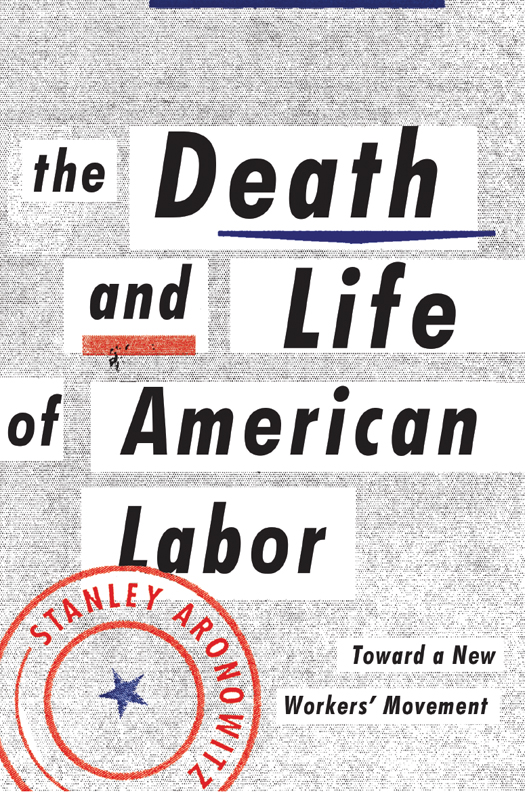

First published by Verso 2014

Stanley Aronowitz 2014

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-138-1 (HB)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-194-7 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-007-4 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Aronowitz, Stanley.

The death and life of American labor : toward a new workers movement / Stanley

Aronowitz.

pages cm

Summary: Union membership in the United States has fallen below 11 percent, the lowest rate since before the New Deal. Longtime scholar of the American union movement Stanley Aronowitz argues that the labor movement as we have known it for most of the last 100 years is effectively dead. And he asserts that this death has been a long time comingthe organizing principles chosen by the labor movement at midcentury have come back to haunt the movement today. In an expansive survey of new initiatives, strikes, organizations and allies Aronowitz analyzes the possibilities of labors renewal, and sets out a program for a new, broad, radical workers movementProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-1-78168-138-1 (hardback)ISBN 978-1-78168-194-7 (ebk)

1. Labor movementUnited StatesHistory21st century. 2. LaborUnited StatesHistory21st century. 3. Labor unionsUnited StatesHistory21st century. I. Title.

HD8072.5.A759 2014

331.880973dc23

2014018867

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

Contents

PREFACE

Union Defeat at Volkswagen

A merica is a winner-take-all culture. Some European countries allow proportional representation, recognizing the right of minority unions to participate in legislatures and collective bargaining, but not the United States. The landmark National Labor Relations Act of 1935 mandated our current playbook for union representation, in effect reversing a century of plural unionism in many workplaces. Under the law, although more than one union can vie for the right to represent a single bargaining unit, if the petitioner seeks exclusive representation then ultimately the unit can only be represented by a single union. Thus the minority organization is excluded from participation in collective bargaining and other shop-floor matters until the contract termination, after which it can seek, via an election supervised by the Labor Board, to replace the prevailing monopoly labor organization with a monopoly of its own. Before the postwar era, many unions sought minority bargaining rights, but abandoned this strategy in favor of winner take all.

Long neglected by organized labor, the largely nonunion South has finally become a focus of interest for the United Auto Workers. More than a decade ago, the UAW was soundly defeated in two board election bids to organize the Nissan plant in Smyrna, Tennessee, and until recently it refrained from risking a third humiliation. However, by the 2000s, thirteen European and Japanese car companies had opened assembly plants in the American South and border states. Nissan, Mercedes, Toyota, and Volkswagen are among the foreign companies that have transplanted some of their facilities to the United States. And the South has been a favored corporate target for obvious reasons: all Southern states and some border states have right to work laws that prohibit the union shop, and the regions antiunion environment in general is stifling; the states governments are eager to provide huge cash grants to corporations that locate there; and taxes are generally much lower than in the Northeast and Midwest or on the West Coast. General Motors and Ford, too, have closed numerous plants in the Northeast and Midwest and built new facilities in the South for these reasons and more.

The South has some of the characteristics of an internal colony. It is a historically agricultural region whose residents earn significantly lower incomes than their Northern counterparts. Its geography includes sparsely populated areas that have long suffered sporadic, seasonal, and low-wage employment, making them highly favorable for plant location. The UAW sanctioned these moves by U.S. companies as long as the companies agreed to allow unionization. But the transplanted factories have mostly resisted becoming union shops even when their home-base factories are unionized. The expanding number of transplants forced a reluctant UAW to reconsider its organizing program and to venture south.

For several years UAW has conducted four Southern organizing campaignsat Nissans huge plant in Canton, Mississippi; at Mercedess Alabama factory; Nissan again at Smyrna; and at the Volkswagen assembly plant near Chattanooga, Tennessee, which employs 1,550 workers. The union has declared that it will not seek bargaining rights under the law until a company enters a neutrality agreement. Nissan has displayed characteristic hostility to unionization, refusing to grant even a neutrality agreement, one in which the company pledges not to interfere with the unions organizing effort. Volkswagen, however, was glad to agree to noninterference. Its German facilities are all represented by the powerful metalworkers union, IG Metall, which has made its position on the fate of transplants clear: Do not interfere with union organizing unless you, the company, wish to court trouble. And the company, all of whose other plants have works councils, is intensely interested in installing one in the Chattanooga factory. But under U.S. labor law, a works council, which represents both management and labor, cannot be started unless the plants workers have union representation.

Consequently, when the unions campaign was in high gear, not only did the company refrain from the usual antiunion ploysthreats of plant removal, intimidation of activists, and attacks against the union as an illegitimate outsiderit even awarded union representatives access to the plant to talk to the workers and hold organizing meetings. Prior to the election, more than two-thirds of the workers signed union cards. Based on conventional wisdom, everyone, including the organizers, confidently predicted a UAW victory. This confidence was not severely shaken by an outburst of vehement opposition from the states governor, one of its U.S. senators, and a relatively small inside group of antiunion rank-and-file workers. But a week before the scheduled vote, union organizers sensed a turn of the tide. Their anxiety proved to be justified. On February 14, 2014, the union lost the election by 86 votes out of more than 1,300 cast. Yet the real margin was only 44 votes, for if these had gone to the union column, the UAW would have prevailed.

The major networks, the New York Times and other leading metropolitan newspapers, and labor expertshistorians and punditstook the result as a crushing defeat for the union and gravely commented that what happened would make labors future Southern organizing a steep uphill journey. UAW president Bob King agreed with this ominous diagnosis. Indeed, after getting into bed with the company and enjoying in-plant access, union leaders might well have been disappointed in the result. But there is another possible interpretation of it. The UAW had not sought a secret ballot in an election for any transplanted workplace for more than a decade and labor has generally avoided Southern organizing for much longer than that, so the union might have heralded the close vote as an inspiring beginning. It might have declared its intention to stay in the community and form a local union, charged modest dues to those workers who joined, and, eventually, demanded minority representation. But in the immediate aftermath of the election, union response reflected the gloom-and-doom commentary of conservative and liberal media. The winner-take-all mentality, pervasive in labors ranks, overcame the radical imagination.