Josephine Hulett (right), field officer for the National Committee on Household Employment, recruiting household workers. (Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site, National Archives for Black Womens History)

BEACON PRESS

Boston, Massachusetts

www.beacon.org

Beacon Press books are published under the auspices of the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations.

2015 by Premilla Nadasen

All rights reserved

Text design and composition by Kim Arney

Chapter 4 was adapted from Premilla Nadasen, Power, Intimacy, and Contestation: Dorothy Bolden and Domestic Worker Organizing in Atlanta in the 1960s, in Intimate Labors: Cultures, Technologies, and the Politics of Care, 20416, ed. Eileen Boris and Rhacel Salazar Parreas. 2010 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University. All rights reserved. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Stanford University Press, sup.org.

Chapter 6 was adapted from Premilla Nadasen, Citizenship Rights, Domestic Work, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, Journal of Policy History 24, no. 1 (January 2012): 7494. Reprinted with permission Donald Critchlow and Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nadasen, Premilla.

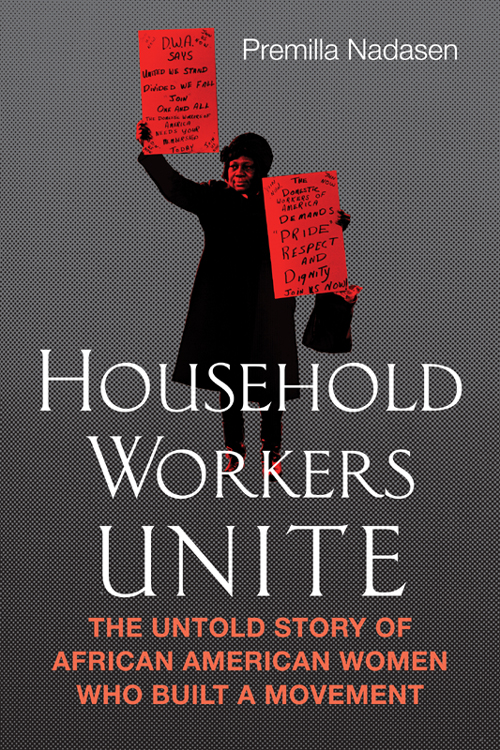

Household workers unite : the untold story of African American women who built a movement / Premilla Nadasen.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8070-1450-9 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-8070-3319-7 (paperback)

ISBN 978-0-8070-1451-6 (ebook)

1. Women household employeesUnited StatesHistory20th century. 2. African American household employeesHistory20th century. 3. Household employeesLabor unionsUnited StatesHistory20th century. 4. Women labor leadersUnited StatesHistory20th century. 5. African American labor leadersUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

HD6072.2.U5N33 2015

331.478116408996073dc23

2015003720

I NTRODUCTION

What matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it.

GABRIEL GARCA MRQUEZ

In 2007 a landscape contractor in the exclusive New York City suburb of Muttontown, on Long Island, was sitting in his truck after purchasing a box of doughnuts when a malnourished, bedraggled woman approached him. Barely speaking English, the woman pointed frantically to her stomach and begged him to give her a doughnut. The woman, as was later learned through media accounts, was a household workerone of two live-in Indonesian workers who had been virtually imprisoned and literally tortured by their employers for five years. They were beaten with rolling pins, scalded with boiling water, force-fed chili peppers, required to sleep on the floor in a closet, and only allowed to leave the house to take out the garbage. The employersa wealthy married couplewere eventually brought to trial, convicted, fined, and sent to jail. This widely publicized case, an extreme but not isolated incident, rightly drew condemnation from many quarters and became emblematic of the vulnerability of private household workers: their isolation, their status as marginalized (and in this case noncitizen) workers, and the vastly unequal power relations that characterize the occupation.

Buried in the sensational news coverage was the fact that an organization of South Asian workersAndolanhad learned of the case and begun to advocate on behalf of the workers. Andolan collaborated with Domestic Workers United (DWU) to organize a public demonstration in front of the courthouse as the trial took place. Founded in 2000 and composed of nannies, cleaners, and elder-care workers, DWU is a multiracial organization that adopted the slogan Tell Dem Slavery Done! Based in New York City, it holds rallies, organizes picket lines, lobbies legislators, and brings lawsuits on behalf of workers to improve labor conditions.

Andolan, DWU, and other organizations in this active and vocal household-workers movement are frequently overlooked in the media, while the victimization storieslike that of the Indonesian workersdominate. Stories of domestic workers who need rescuing often appear in the popular press and circulate through the Internet. In short, the image of the disempowered and abused domestic worker is a common one, evoking pity and outrage.

The victimization theme plays out in the best-selling book and popular 2011 film The Help. Although the story is set in the turbulent decade of the 1960s, the workers profiled are not embroiled in the heroic efforts to overturn Jim Crow segregation or transform southern race relations. In fact, they need prodding and encouragement from the young white protagonist to speak out about their hardship. The story of The Help is one about black domestic life told from the perspective of a white employer and, in the end, reinforces dominant stereotypes of passive household workers. Rarely do we see such workers as agents of history. They exist on the sidelines, serve as a backdrop for the stories of others, or, when they are cast as the main actors, give voice to victimization and oppression. They remain nameless stereotypes, like the elderly black woman who, tired but determined, heroically walks to work rather than ride a segregated bus, or one of the thousands of African Americans filling church pews at a mass meeting in support of civil rights.

Although over one-third of employed black women in the United States labored as domestics in 1960, household workers are oddly invisible in histories of postwar social movements. Many Americans are familiar with iconic stories of political struggles, whether it is Rosa Parkss refusal to relinquish her seat on a racially segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, or the so-called bra burning at the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1968, where womens liberationists threw symbols of gendered oppression into a freedom trash can. These stories are often told in a particular way, with a clear political purpose: to illustrate the dignity in acts of civil disobedience as practiced during the early civil rights movement, in the case of the former; and in the latter, to demonstrate the womens liberation movements opposition to womens objectification. Preachers and students, sanitation workers and sharecroppers, are all given their due in such stories, but not domestic workers.

This book tells the story of household-worker activism from the 1950s to the 1970s, a pivotal period during which domestic workers established a national movement to transform the occupation. It is a story of women, primarily women of color, who have for the most part operated in the shadows of the formal labor movement, on the margins of the struggle for black freedom, and under the heels of the mainstream womens movement. It challenges widespread assumptions about the passivity of domestic workers and paints a markedly different picture of household workersone in which they do not need a savior. But it does more than that. It analyzes their strategies of mobilization and explores how storytelling was central to the way they organized and developed a political agenda. Household-worker activists shared stories that were passed down to them and told stories of their own experiences as workers. Their stories, which they connected to the struggle for black liberation, highlighted the racial exploitation of the labor and were part of a collective remembered history in the African American community. Storytelling was a form of activism, a strategic way to make sense of the past as well as the present and to overturn assumptions about domestic workers.