PREFACE: WHY CALIFORNIA LABOR HISTORY?

Admittedly, a state labor history is an artificial construct. The boundaries of California were drawn in the mid-nineteenth century, based on a brief war with an outgunned Mexico that had only just gotten free of Spanish colonialism. Why should that vanished world exert any influence over the shape of a history about working people striving for their share of the American Dream, written in the twenty-first century? As we all know, international forces, even more than national ones, increasingly define that struggle. States might be considered irrelevant to the dominant economic engines of our time.

And yet no time seems more fitting than now to consider the particular contours of California labor history. In the wake of recent events, its clear that for labor politics, states are where the action is. In states that have elected conservative legislatures, the first order of business has been to roll back worker rights and lawsoften in place for decadesthat enabled working people to call themselves middle class by virtue of their ability to organize collectively on their own behalf.

In Wisconsin, public employee unions no longer have the right to bargain the terms of their members employment. And the Badger State, like former automobile worker union stronghold Michigan, now has a right-to-work law forbidding unions to collect dues from workers who opt out, yet whose jobs are protected through contracts negotiated by those unions.

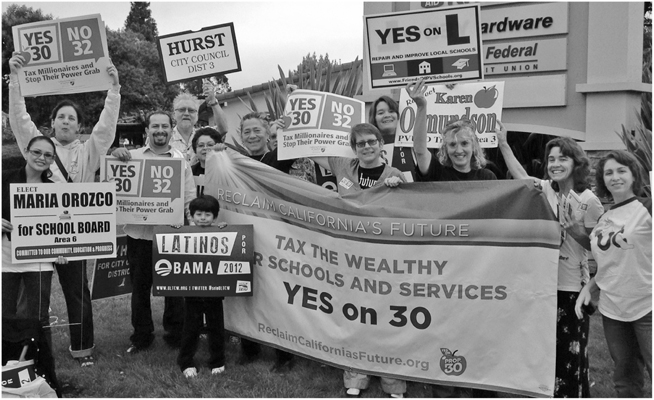

In California, however, unions led a successful campaign in the 2012 elections to defeat a similar policy placed on the state ballot by antiunion forces. And despite the reputation of the Golden State as an antitax stronghold, the labor movement also steered to victory a measure to increase income taxes on the wealthiest Californians in order to fund schools and services starved for decades. The two campaigns reverberated with one another; class themes emerged as the electorate voted to defend worker rights and demand that the wealthy pay a fairer share of taxes.

FIGURE 1. Union members and community supporters in Watsonville helped stop an antiunion ballot measure, Proposition 32, and pass a tax on the wealthy, Proposition 30, in the 2012 statewide election. Francisco Rodriguez, photo.

When we ask, Whats the difference between California and these other states? we begin to see why now might be a good time for a state labor history. California has been famous for its exceptionalism since the Gold Rush: fine weather, the vast riches in its extractive industries, its literal edginess at the far western end of the pioneer trail on the Pacific Rim, and the recurrent eruptions of various gold rushes that seem to suggest Horatio Alger perpetually makes his home here. But what seems exceptional often turns out to be a variation on tendencies shared with the rest of the country.

In 1978, it seemed exceptional when the states voters overwhelmingly passed Proposition 13, which rolled back property tax rates and set a two-thirds supermajority bar for legislative passage of any tax. The action reversed decades of the New Deal consensus that the role of government is to provide services for the common good, and replaced it with an experiment in low taxes, small government, and the joint demonization of public employees (providers of services) and people of color in poverty (recipients of services).

But within two years, the elevation of native son Ronald Reagan to the presidency showed that California was just the wedge state for a national program tilting the playing field away from the most good for the most people to big business and the rich. California may be ahead of the curve, but probably only a bit farther down the same track.

FIGURE 2. Californias unions have embraced immigrant workers on a scale and with tactics largely unseen elsewhere. David Bacon, photo.

So it may be with the states labor movement. An historian only attempts to predict the future on the basis of the past with caution. But here is a safe bet. The demographic trend by which immigrant workers have fueled Californias population increases will continue, in California and increasingly in other states. The high proportion of immigrants who come to this land to work ensures that a sizeable number will bring along familiarity with, and often sympathies for, the goals of organized labor. In some cases, that will include personal histories of union involvement.

Recent working-class immigrants, once theyve become citizens, have tended to vote in lower numbers than people who have been here longer. But one major difference between Californias unions and those in other states has been the embrace of immigrant workers on a scale, and with tactics, unseen elsewhere. Labors voter education and mobilization programs aimed at infrequent voters have come on the heels of organizing outreach to concentrations of immigrant workers in service and manufacturing jobs.

Unless older white workers begin reproducing at a more rapid ratean unlikely developmentyounger workers of color, including a high proportion of immigrants, are the future face of the workforce and the electorate. Because the labor movement has understood this fact and designed its efforts around it, Californias unionization rate remains at 16 percent while the national average is 11 percent.