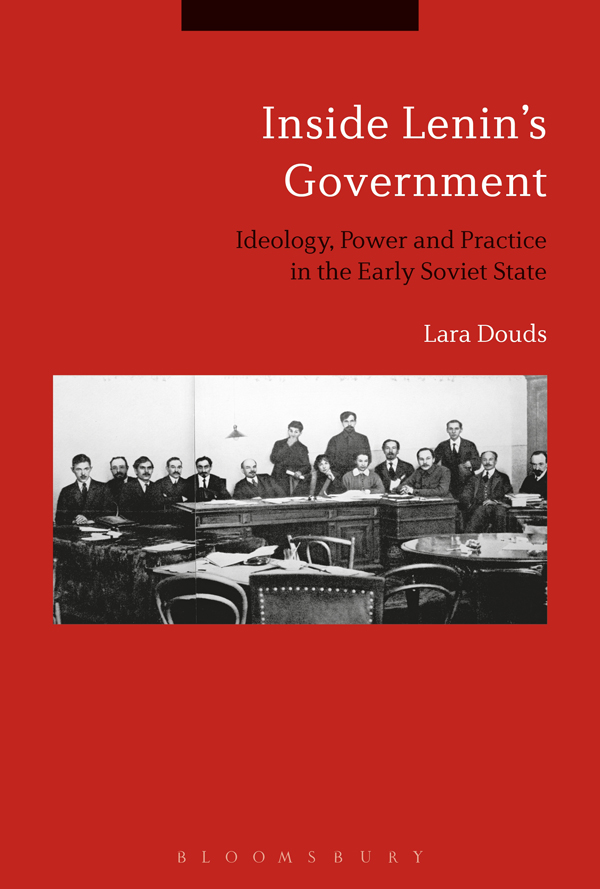

Inside Lenins Government

Inside Lenins Government

Ideology, Power and Practice in the Early Soviet State

Lara Douds

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Contents

My chief debt of gratitude is to Professor David Saunders. Always generous with his time and endless wisdom throughout the life of this project, he read and criticized draft chapters and gave support and assistance at difficult moments, both academic and personal. I should also like to thank Dr Matthew Rendle, who helped with the planning of this project. I also owe thanks to Dr Marianna Taymanova, who taught me Russian, inspired me and assisted with practicalities in arranging my research visits to Russia.

I am grateful to the Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding, and also to the Royal Historical Society, British Association of Slavonic and East European Studies, and Newcastle University School of Historical Studies, for providing grants for additional research trips to Moscow.

Thanks are due to the staff of British Library, the Russian State Library, the Russian State Archive of Social and Political History (RGASPI) and the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF) where most of my research was conducted. I would also like to thank my teachers and the staff of the International Office at the Russian State University for the Humanities (RGGU) where I stayed in Moscow while conducting the archival research.

As I developed the manuscript, advice and critique from James Harris were invaluable. I am very grateful for his clarity of thought and infectious passion for the subject. I am also grateful to the members of the Study Group on the Russian Revolution and the Association for Slavic, East European and Eurasian Studies who allowed me the opportunity to discuss my research and provided useful feedback. Geoff Swain, Chris Read, Aaron Retish, Katy Turton, Alexis Pogorelskin, Lars Lih and Tony Heywood all lent their wisdom on particular questions. Also, thanks are due to my colleagues at the University of York, in particular David Moon, and my fellow Newcastle kruzhok members Charlotte Alston, Robert Dale and again David Saunders; our weekly lunchtime assembly kept me sane during the final stages of producing the manuscript.

I am enormously grateful to my parents for their support and encouragement throughout my studies. Most of all, thanks to my husband Brian who tolerated the prolonged presence of Lenin and the Bolsheviks in our home with patience and humour and to our baby son Hugo whose early arrival helped focus the mind and strengthen the determination to finish the book.

This book employs the Library of Congress system of transliteration from the Cyrillic into the Latin alphabet, with some simplifications. Some frequently used proper names are spelled in their more usual English forms where appropriate (Trotsky and Osinsky, but Krestinskii).

Dates before January 1918 (when the Soviet government modernized their calendar) are given according to the Julian calendar then in use in Russia, which ran thirteen days behind the Gregorian calendar in the West.

| CHEKA | (Chrezvychainaia komissiia po bor'be s kontrrevoliutsiei i sabotazhem) The Emergency Commission for Combating Counter-Revolution and Sabotage |

| GOSPLAN | (Gosudarstvennaia obshcheplannovaia komissiia) State General Planning Commission |

| MRC | (Voenno-revoliutsionnyi komitet) The Military Revolutionary Committee |

| NEP | (Novaia ekonomicheskaia politika) New Economic Policy |

| ORGBURO | (Organnizatsionnyi Biuro TsK RKPb) The Organizational Bureau of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) |

| POLITBURO | (Politicheskii Biuro TsK RKPb) The Political Bureau of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) |

| RABKRIN | (Raboche-krestianskaia inspektsiia) The Worker-Peasant Inspectorate |

| SOVNARKOM | (Sovet Narodnykh komissarov) The Council of Peoples Commissars |

| TsK RKP (b) | (Tsentralnyi komitet rossiskoi kommunisticheskoi partii [Bolshevik]) Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party (Bolshevik) |

| VESENKHA | (Vserossiiskii sovet narodnogo khoziaistva) The National Economic Council |

| VTsIK Sovetov | (Vserossiiskii Tsentralnyi Ispolnitelnyi Komitet) The All Russian Central Executive Committee of Soviets |

Russia began its tumultuous twentieth century as a decrepit autocratic empire until the strains of the First World War finally brought the tsarist regime crashing down. In 1917, two revolutions swept through Russia, ending three centuries of Romanov rule. In February, growing civil unrest, coupled with chronic food shortages, erupted into popular open revolt, forcing the abdication of Nicholas II, the last Russian tsar.

A committee of the Duma, the quasi-parliamentary body created after Russias failed 1905 Revolution, appointed a Provisional Government, but it faced a rival in the Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies whose 2500 delegates were elected from factories and military units in and around the capital. The Soviet soon proved that it had greater authority than the Provisional Government, which sought to continue Russias participation in the European war. On 1 March the Petrograd Soviet issued its famous Order No. 1, which directed the military to obey only the orders of the Soviet and not those of the Provisional Government. Between March and October the Provisional Government was reorganized four times. The initially liberal government evolved in to a series of coalitions with moderate socialists. None, however, proved able to cope adequately with the major problems afflicting the country: peasant land seizures, economic dislocation, nationalist independence movements in non-Russian areas and the collapse of army morale at the front. But while the Provisional Governments power waned as it was unable to halt Russias slide into political, economic and military chaos, that of the Soviets was increasing as more sprung up in cities and towns across the country and in the army. By autumn the Bolsheviks radical program of peace, bread and land had won the party considerable support among the hungry urban workers and the soldiers, who were already deserting from the ranks in large numbers. Further, the Bolsheviks now held majorities in Soviets across Russia and dominated in the Petrograd Soviet in the centre. Lenin made repeated attempts to persuade his party to topple the Provisional Government and by mid-October the Bolsheviks had established a Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC) of the Petrograd Soviet to carry out this action. On 2425 October the Bolshevik and Left Socialist Revolutionary MRC staged a nearly bloodless coup, occupying government buildings, telegraph stations and other strategic locations, timed to coincide with the opening of the Second Congress of Soviets, to pass power into its hands. The Bolsheviks came to power, not because they were cynical opportunists, but because their policies, formulated by Lenin from April onwards and shaped by the events of the following months, placed them at the head of a genuinely popular movement.

The October Revolution delivered the birth of the worlds first workers and peasants socialist state, the Soviet Republic. In constructing their post-revolutionary government, Lenin and his fellow Soviet leaders were inspired by Marxist ideals of freeing the working masses from oppression and inequality and aimed to introduce the most democratic society in history. Instead, they inadvertently ushered in an authoritarian Communist party-state dictatorship which was even more brutal than anything even the tsars had managed to impose. Yet, as Smith has warned, We shall never understand the Russian Revolution unless we appreciate that the Bolsheviks were fundamentally driven by outrage against the exploitation at the heart of capitalism and the aggressive nationalism that had led Europe into the carnage of the First World War. The hideous inhumanities that resulted from the revolution, culminating in Stalinism, should not obscure that fact that millions welcomed the revolution as the harbinger of social justice and freedom.