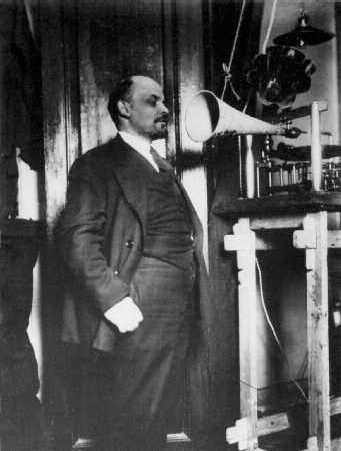

Lenin, faced with new technology for spreading the word, seems somewhat nonplussed (March 1919).

Introduction

On the shelves of my study, in serried ranks of blue, stand the 55 volumes of the fifth edition of the works of V. I. Lenin. In their way, these volumes equipped with a fantastically elaborate scholarly apparatus detailing every name, book and even every proverb mentioned by their author are the building blocks of an intellectual mausoleum comparable to the corporeal mausoleum that still stands in Moscow. Just as impressive an accomplishment of what might be called embalming scholarship is the multivolume Vladimir Ilich Lenin: Biograficheskaia Khronika, consisting of over 8,000 pages detailing exactly what Lenin did on every day for which we have information (usually he was writing an article, issuing an intra-party protest, making a speech).

And yet the very title of this biokhronika points to a biographical puzzle, since the name Vladimir Ilich Lenin is a posthumous creation. The living man went by many names, but Vladimir Ilich Lenin was not among them. Posteritys need to refer to this man with a name he did not use during his lifetime gives us a sense of the difficulty of capturing the essence of this passionately impersonal figure without mummifying him, either as saint or as bogeyman.

What should we call him? He was christened, shortly after his birth in 1870, as Vladimir Ilich Ulyanov. Ilich is a patronymic, meaning son of Ilya. And yet, for many during his lifetime and after, Ilich conveyed a greater sense of the individuality of the man than Vladimir. As soon as he started on his revolutionary careerin the early 1890s the exigencies of the underground led our hero to distance himself from his given name. The surviving copy of his first major written production Who are these Friends of the People and How Do They Fight against the Social Democrats? (1893) has no authorial name on the title-page. In works legally published in the 1890s our hero adopted more than one new name: K. Tulin or (for his magnum opus of 1899, The Development of Capitalism in Russia) Vladimir Ilin, a pseudonym that hardly hides his real name. Right up to the 1917 revolution, legally published works by Vl. Ilin continued to appear.

Even in a legally published newspaper an underground revolutionary had to exercise care so that his identity would not serve as an excuse to fine it or shut it down. One such paper was the Bolshevik Pravda, published in Petersburg from 1912 to 1914. A close colleague of Lenin, Lev Kamenev, later recalled that in order not to compromise this newspaper Ilich changed the signature to his articles almost every day. In Pravda his articles were signed with the most diversified combinations of letters, having nothing in common with his usual literary signature, such as P.P., F.L.-ko., V.F., R.S., etc., etc. This necessity of constantly changing his signature was still another obstacle between the words of Ilich and his readers the working masses.

Our hero acquired his usual literary signature around 1901, while serving as one of the editors of the underground newspaper Iskra, when he began to sign his published work as N. Lenin. Why Lenin? We have already seen a certain fondness for pseudonyms ending in -in. But Lenin seems to have been the name of an actual person whose passport helped our man leave Russia in 1900. This passport was made available to Lenin, at second or third hand, as a family favour; in the end, he did not have to use it.

N. Lenin, not V. I. Lenin. His published works, right to the end, have N. Lenin on the title-page. What does the N stand for? Nothing. Revolutionary pseudonyms very often includedmeaningless initials. But when N. Lenin became world famous, the idea got about that N stood for Nikolai an evocative name indeed, combining Nikolai the Last (the tsar replaced by Lenin), Niccol Machiavelli and Old Nick. In 1919 one of the first more-or-less accurate biographical sketches in English proclaimed its subject to be Nikolai Lenin. President Ronald Reagan was still talking about Nikolai Lenin in the 1980s and perhaps this name is just as legitimate historically as V. I. Lenin.

Title-page of What Is to Be Done? (1902), one of the first publications bearing the name N. Lenin. |

|