Lenin Vladimir Ilʹich - Lenins Moscow

Here you can read online Lenin Vladimir Ilʹich - Lenins Moscow full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Soviet Union, year: 2016, publisher: Haymarket Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Lenins Moscow

- Author:

- Publisher:Haymarket Books

- Genre:

- Year:2016

- City:Soviet Union

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Lenins Moscow: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Lenins Moscow" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Lenins Moscow — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Lenins Moscow" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Introduction

by Ian Birchall

r evolutionaries have to know both how to swim against the stream and how to swim with it. When the workers movement is in retreat, when the traditional organisations of the left are crumbling around them, they have to hold firm to a clear and principled analysis without bending to the pressures of the times. But such tenacity is useless unless, when a new phase of mass struggle begins, they can respond quickly and imaginatively to it, and give the leadership that is required.

Alfred Rosmer, the author of Lenins Moscow , faced both these tasks. In his long life as a revolutionary he went on fighting for his vision of internationalist socialism when the European labour movement collapsed in 1914, during the high tide of the years following 1917, and then through the bleak, bitter isolation that came when the Russian Revolution was betrayed and lost.

Rosmerhis family name was Griotwas born in New York in 1877 to French parents. They had not been directly involved in the Paris Commune of 1871, but probably left France because of the period of repression that followed it. The family returned to France in 1884. Rosmer became an office-worker, then an employee of the Prfecture de la Seine and a proof-reader. The name Rosmer, which he used throughout his life, was taken from the hero of Ibsens Rosmerholm , an incurable idealist.

Rosmer began his political life as an anarchist around 1896 at the time of the Dreyfus case; he evolved towards revolutionary syndicalism and in the years before 1914 worked with Pierre Monatte on the journal La Vie Ouvrire . As an intransigent syndicalist he refused all contact with organisations of the Second International. Rosmer was also a resolute advocate of the right of women to take employment, something rejected by many French trade unionists at this time. In 1913 he was involved in supporting Mme Couriau, a Lyons woman who had taken a job as a printing worker. Not only did the union refuse to accept her into membership, but it instructed her husband to tell her to give up her job, and, when he refused, expelled him from the union.

Rosmers first experience of a sudden massive shift in the level of class struggle came in 1914. In the last week of July 1914 there was a huge anti-war demonstration in Paris, so large that the police could not control it. Syndicalists and socialists alike betrayed; only a tiny handful kept internationalism alive. From October 1914 Rosmer and a minute group of anti-war militants met weekly at the Vie Ouvrire office. They were joined by a Russian exile who had fed from Vienna at the outbreak of war, one Leon Trotsky. Rosmer worked to prepare for the Zimmerwald Conference, but did not himself attend as he was conscripted in May 1915. The limited anti-war propaganda that was possible was forced into clandestine channels; Rosmers pamphlet on Zimmerwald was published in a small format so that it could be distributed unobtrusively in ordinary letter-sized envelopes.

With the new wave of struggle that followed the Russian Revolution, Rosmer had to reconsider his previous political allegiances. He now devoted himself entirely to the building of the Communist International; between 1920 and 1924 he held numerous posts of responsibility in both the International and the French Communist Party. The contribution of Rosmer and others like him was highly valued by Lenin and Trotsky. Trotsky recalls that on one occasion Lenin said to him: Couldnt we advise the French Communists to throw out those corrupt parliamentarians like Cachin and Frossard, and replace them with the Vie Ouvrire group?

But Rosmers dedication to the revolution did not blind him to its weaknesses, and he was one of the first to recognise the degeneration of the International. Together with Monatte and Souvarine he sided with Trotsky from the beginning of his struggle against Stalin; they published Trotskys articles on the New Course in French. Yet the opposition of Rosmer and his friends was so firmly based in Leninism that it was necessary for Treint and his associates in the party leadership to distort the issues totally and present them as a Right Opposition. (The charge was largely based on Rosmers opposition to Lozovskys claim in LHumanit of 2 February 1924 that the British Labour government represented a victory of the bourgeoisie over socialism.)

Rosmer, Monatte and Delagarde were expelled by an extraordinary conference of the French Communist Party in December 1924. The conference was called at four days notice and most of the delegates had not read the open letter to party members which was the main ground for expulsion. Rosmer declared: We will work from outside to hasten the day when the party becomes a real communist party. And in 1925 he joined with Monatte in founding La Rvolution Proltarienne .

For the rest of his life Rosmer remained an uncompromising revolutionary. He strove to build a left opposition tendency in France, and in the 1929-30 period he worked closely with Trotsky in the attempt to regroup the international left opposition. But in 1930 he broke with Trotsky over what he considered the excessive trust the latter was putting in Molinier. Rosmer was later personally reconciled with Trotsky, and visited him in Mexico in 1939. He participated in the Committee for Inquiry into the Moscow Trials and the Defence of Free Opinion in the Revolution and in the Dewey Commission. He never again, however, formally involved himself in the Trotskyist movement. (His disagreement with Trotsky on the class nature of Russia may have been one of the reasons for this.) After Trotskys death Rosmer was asked by Natalia Sedova to find European publishers for Trotskys works.

Rosmer remained a Leninist and an anti-Stalinist until the day of his death in 1964. It is possible to criticise some of his detailed positions, such as his willingness to accept the Congress for Cultural Freedom as authentic anti-Stalinists,

Above all, Rosmer wrote. His most substantial work was his study of working-class opposition to the First World War, Le mouvement ouvrier pendant la guerre . This combines scrupulous documentation with a record of personal involvement.

But it is Lenins Moscow (Moscou sous Lnine) that remains Rosmers most relevant and readable work. It was originally published in the bleak year of 1953. After launching a last wave of purges, Stalin departed this life; his heirs fought for his succession with squalid ruthlessness, but friend and foe alike accepted the orthodoxy that Stalin was Lenins true heir. In the United States McCarthy was at the peak of his witch-hunting power, tracking down ex-Communists, while in France a series of right-wing governments were attacking the living standards and organisation of the working class.

The Cold War seemed to have led the working classand with it the whole of humanityinto a dead-end. The working class was not, however, so easily silenced. This was also the year of the East Berlin rising. In France a strikeoriginally called by anarcho-syndicalists in the Bordeaux post officespread to four million workers.

There are, of course, numerous other histories of the early years of the Communist Internationalmany bad, a few good. But Rosmers text is especially valuable, if not unique, in that it combines careful historical analysis with a record of personal experience. The truth is always concrete, and Rosmer shows us how the principles and policies of the Comintern were put into practice by real human beings, with their individual strengths, eccentricities and failings.

Not that Rosmer believed that individual character was the major determining factor in history. On the contrary, he shows how a period of massive social struggle transformed the characters of those called on to play leading roles. The success of the revolution brought out the best in many revolutionaries; but as the tide turned and Russia found itself isolated, the crisis of the movement manifested itself through individual weaknesses.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

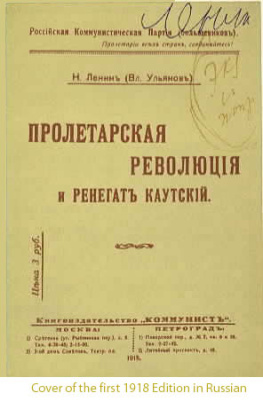

Similar books «Lenins Moscow»

Look at similar books to Lenins Moscow. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Lenins Moscow and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.