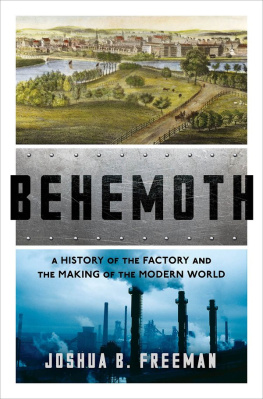

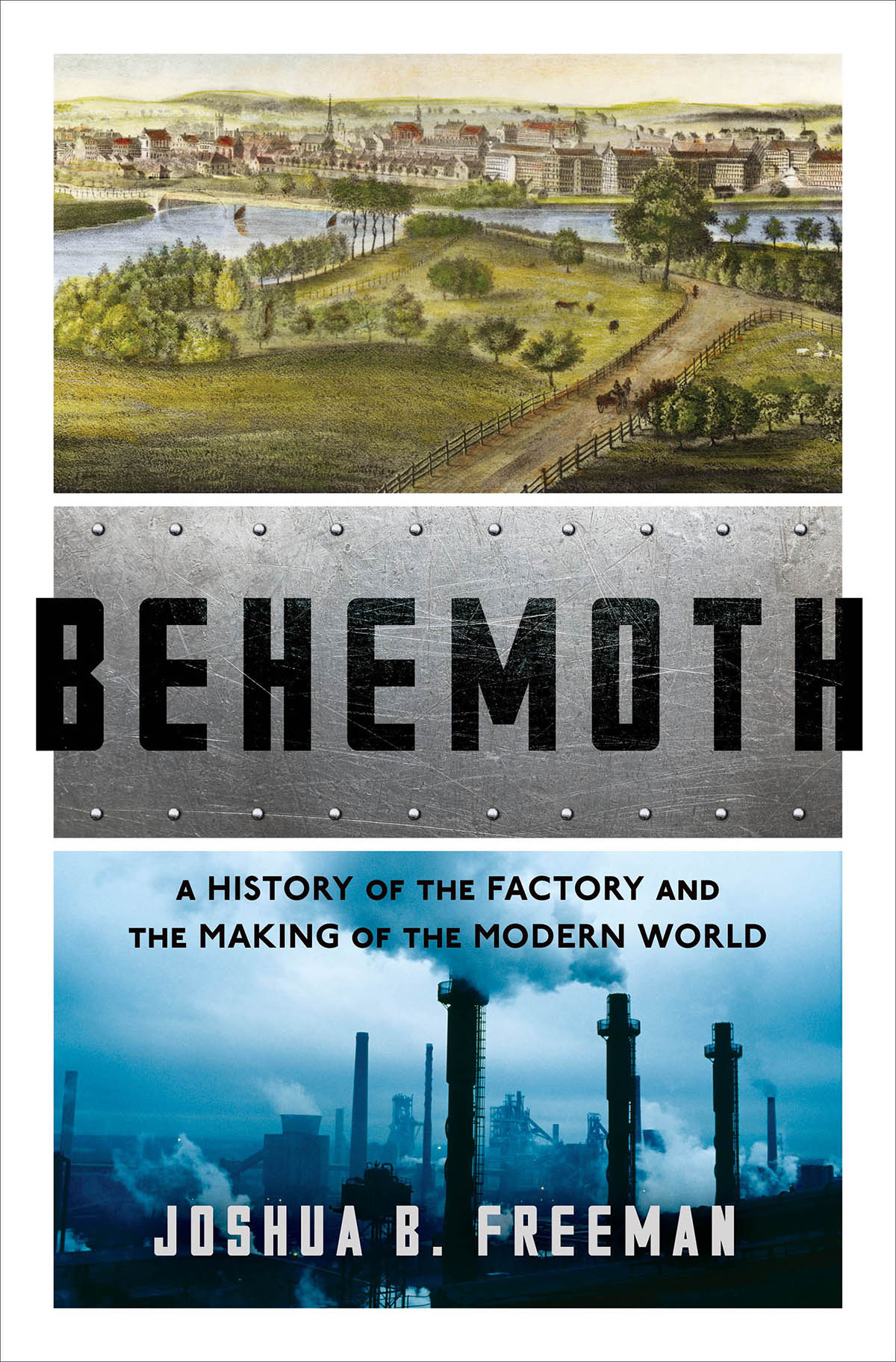

BEHEMOTH

A HISTORY OF THE FACTORY

AND THE MAKING OF THE

MODERN WORLD

Joshua B. Freeman

As always,

for Debbie, Julia, and Lena

Rereading your book has made me regretfully aware of our increasing age. How freshly and passionately, with what bold anticipations, and without learned and systematic, scholarly doubts, is the thing still dealt with here! And the very illusion that the result will leap into the daylight of history tomorrow or the day after gives the whole thing a warmth and vivacious humourcompared with which the later gray in gray makes a damned unpleasant contrast.

Karl Marx, in an 1863 letter to Friedrich Engels

about The Condition of the Working Class in England

At sea, the sailors manufacture a clumsy sort of twine, called spun-yarn . For material, they use odds and ends of old rigging called junk , the yarn of which are picked to pieces, and then twisted into new combinations, something as most books are manufactured.

Herman Melville,

Redburn: His First Voyage (1849)

Contents

The Invention of the Factory

New England Textiles and Visions of Utopia

Industrial Exhibitions, Steelmaking, and the Price of Prometheanism

Fordism, Labor, and the Romance of the Giant Factory

Crash Industrialization in the Soviet Union

Cold War Mass Production

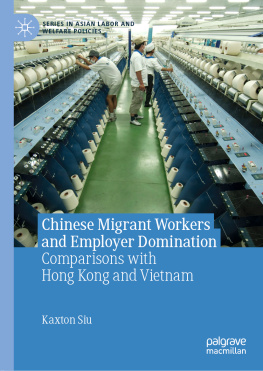

Giant Factories in China and Vietnam

W E LIVE IN A FACTORY-MADE WORLD, OR AT LEAST most of us do. Almost everything in the room I am writing in came from a factory: the furniture, the lamp, the computer, the books, the pencils and pens, the water glass. So did my clothes, shoes, wristwatch, and cell phone. Much of the room itself was factory made: the sheetrock walls, the windows and window frames, the air conditioner, the parquet floor. Factories produce the food we eat, the medicines we take, the cars we drive, the caskets we are buried in. Most of us would find it extremely difficult to survive, even for a brief time, without factory-made goods.

Yet in most countries, except for factory workers themselves, people pay little attention to the industrial facilities on which they depend. Most consumers of factory products have never been in a factory, nor do they know much about what goes on inside one. In the United States, it is the absence of factories rather than their presence that gets publicized. The loss of roughly five million manufacturing jobs between 2000 and 2016a big story, as when in 2010 the mistreatment of Chinese workers who assembled iPhones and other electronic gear briefly became subject to international scrutiny.

Things werent always this way. Factories, especially the largest and most technically advanced, were once objects of great wonder. Writers, from Daniel Defoe and Frances Trollope to Herman Melville and Maxim Gorky, marveled at them, or were horrified. Tourists, ordinary and celebratedAlexis de Tocqueville, Charles Dickens, Charlie Chaplin, Kwame Nkrumahvisited them. In the twentieth century, they became a favorite subject of painters, photographers, and filmmakers, leading artists like Charles Sheeler, Diego Rivera, and Dziga Vertov. Political thinkers, from Alexander Hamilton to Mao Zedong, debated their significance.

From eighteenth-century England on, observers recognized the revolutionary nature of the factory. Factories visibly ushered in a new world. Their novel machinery, workforces of unprecedented size, and outflow of uniform products all commanded attention. So did the physical, social, and cultural arrangements invented to accommodate them. Producing vast quantities of consumer and producer goods, giant industrial enterprises brought a radical break from the past, in material life and intellectual horizons. The large factory became an incandescent symbol of human ambition and achievement, but also of suffering. Time and again, it served as a measuring rod for attitudes toward work, consumption, and power, a physical embodiment of dreams and nightmares about the future.

In our time, the ubiquity of factory-made products and the lack of novelty in the existence of the factory has dulled appreciation of the extraordinary human experience associated with it. At least in the developed world, we have come to take factory-made modernity for granted as a natural condition of life. Yet it is anything but. Only a brief flash in the history of humankind, the age of the factory does not go as far back as Voltaires first play or the whaling ships of Nantucket. The creation of the factory required exceptional ingenuity, obsession, and misery. We have inherited its miraculous productive power and long history of exploitation without giving it much thought.

But we should. The factory still defines our world. For nearly half a century, scholars and journalists in the United States have been announcing the end of the industrial age, seeing the country as transforming into a postindustrial society. Today, only 8 percent of American workers are in manufacturing, down from 24 percent in 1960. The factory and its workers have lost the cultural purchase they once had. But worldwide, we are in a heyday of manufacturing. According to data compiled by the International Labor Organization, in 2010 nearly 29 percent of the global workforce labored in industry, down only a bit from a 2006 prerecession high of 30 percent and considerably above the 1994 figure of 22 percent. In China, the worlds largest manufacturer, in 2015, 43 percent of the workforce was employed in industry.

The biggest factories in history are operating right now, making products like smartphones, laptops, and brand-name sneakers that for billions of people around the world define what it means to be modern. These factories are staggeringly large, with 100,000, 200,000, or more workers. But they are not without precedent. Outsized factories have been a feature of industrial life for more than two centuries. In each era since the factory arrived on the stage of history, there have been industrial complexes that have stood out on the social and cultural landscape by dint of their size, their machinery and methods, the struggles of their workers, and the products they produced. Their very namesLowell or Magnitogorsk or now Foxconn Cityhave broadly evoked sets of images and associations.

This book tells the story of these landmark factories as industrial giantism migrated from England in the eighteenth century to the American textile and steel industries in the nineteenth century, the automobile industry in the early twentieth century, the Soviet Union in the 1930s, and the new socialist states after World War II, culminating in the Asian behemoths of our time. In part, it is an exploration of the logic of production that led at some times and places to the intense concentration of manufacturing in massive, high-profile facilities and at other times and places to its dispersion and social invisibility. Equally, it is a study of how and why giant factories became carriers of dreams and nightmares associated with industrialization and social change.

Next page