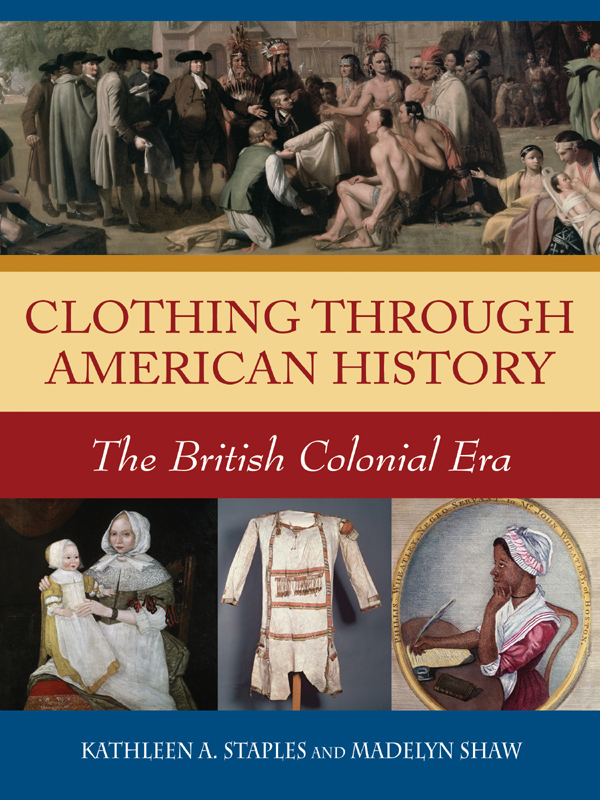

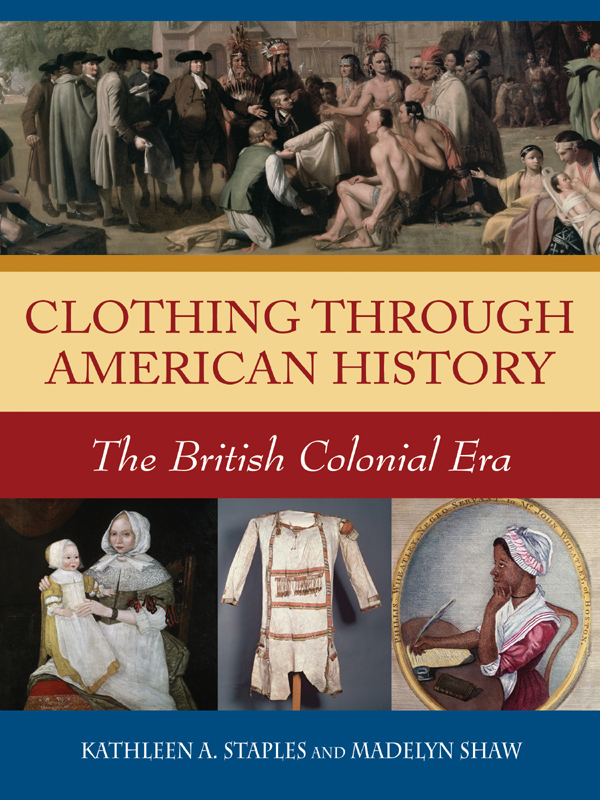

Clothing through American History

Clothing through American History

THE BRITISH COLONIAL ERA

Kathleen A. Staples and Madelyn Shaw

AN IMPRINT OF ABC-CLIO, LLC

Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England

Copyright 2013 by Kathleen A. Staples and Madelyn Shaw

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Staples, Kathleen A.

Clothing through American history : the British colonial era / Kathleen A. Staples and Madelyn Shaw.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-313-33593-8 (hardcopy : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-313-08460-7 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dressUnited StatesHistory. 2. Clothing and dressSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory. 3. United StatesSocial life and customsTo 1775. 4. United StatesSocial conditionsTo 1865. I. Shaw, Madelyn. II. Title.

GT607.S78 2013

391.00973dc23 2013000307

ISBN: 978-0-313-33593-8

EISBN: 978-0-313-08460-7

17 16 15 14 13 1 2 3 4 5

This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook.

Visit www.abc-clio.com for details.

Greenwood

An Imprint of ABC-CLIO, LLC

ABC-CLIO, LLC

130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911

Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911

This book is printed on acid-free paper

Manufactured in the United States of America

Contents

Preface

Between the founding in 1607 of the first permanent settlement in British North America, in Jamestown, and the end of the American Revolution, in 1785, about 430,000 English, more than 260,000 Africans, 145,000 Scots, 100,000 Germans, and countless thousands of other continental Europeans had emigratedforcibly or of their own free willto settle in Britains 13 colonies. By 1775, immigration and natural increase had expanded the population of these nonindigenous inhabitants to 2.5 million. In the process of colonization, European and African immigrants encountered Native People, whose numbers had already deeply declined due to diseases introduced by Spanish explorers in the late 15th and 16th centuries. The population of Native Americans continued to diminish throughout this period as those of the colonists swelled.

Regardless of the ethnic, racial, and/or economic status of the inhabitants of colonial Americaand although legal and logistical challenges influenced the choices these people made about what they worefashion in dress was one of the primary agents that fueled colonial economies and ultimately helped shape the colonists shared experience as consumers prior to the Revolutionary War. As fashion, dress was, to paraphrase one scholar, socially digested to some extent by all levels of colonial society, whether free or enslaved, indigenous or immigrant (Cumming 1984, 1216). This volume, Clothing through American History: The British Colonial Era, explores the increasing importance of dress in the colonial setting in the contexts of settlement patterns, social pressures and preferences, fashion technology, the clothing trades, and the change of fashion through time.

Colonial North America was a colorful place. Not everyone dressed in sober colors or subdued patterns. Although portraits of the well-to-do often depict men in browns, blacks, and greens and the women in blue or brown satin or gold, brown, green, or ivory damask, in reality all social and economic ranks wore a range of colors and patterns.

Unlike probate inventories and merchants advertisements, which do not necessarily need to describe clothing items by color or pattern, notices for stolen or lost goods usually do, as color and pattern could identify an item for recovery. In 1740, for example, a womans light red riding hood and a boys red great coat were lost in Boston (Boston News-Letter, July 31, 1740). A year later a green broadcloth suitcoat, jacket, and breechesall lined with blue taffeta, a black broadcloth coat and jacket, and a dark cinnamon broadcloth coat were stolen from a Boston house (Boston News-Letter, July 9, 1741). In just a handful of lost-and-stolen advertisements from the Pennsylvania Gazette, run between 1735 and 1773, the following fabrics were described:

chintzes and calicoes: sky-colored sprigged with red; green flowered with red and white; red and purple spotted; purple and white with bold red flowers; white with a black pattern like the ace of spades; black with white spots; white with a flower pattern like a strawberry leaf and butterfly.

silks: striped; flowered striped; yellow and white shot; blue and white shot; chestnut colored; light blue; red, yellow, and white striped.

linens: red striped; purple striped; yellow striped; yellow and blue striped.

The cost of a fabric did not dictate how richly colored or patterned it would be. The upper ranks may have sported attire fashioned from luxury fabrics like brocaded silks and flowered chintzes, but the indentured and the enslaved got themselves noticed as well. A sampling of womens clothing from runaway advertisements documents red petticoats, cloaks, and shoes; striped gowns; a red gown with white spots; a brown and yellow gown with a blue petticoat; and a blue worsted damask striped petticoat. Mens jackets and waistcoats were black and white, mingled red, yellow, or green striped; and cinnamon, brown, blue, yellow, white, red, claret, and olive colored. Their coats could be colored pale or deep blue, cinnamon, reddish-brown, white and reddish, black and white, orange, yellowish, or pink. Breeches as well could be black and white, blue and white, or ticking striped, and colored red or blue.

In the colonial period it is perhaps a misnomer to talk about fashion as an industry. Clothing was not constructed in large factories, and the mechanisms of labor specialization, mass production, and distribution of goods that mark the Industrial Revolution were yet to be developed and perfected. Yet in Britain the manufacture of worsted and woolen fabrics for dress as well as the trades that produced ready-made clothing and the accessories of dress were of great commercial importance to the country. The products of these manufactures joined silks woven in France and Italy; innumerable types of linen fabrics produced in the Netherlands and what is now Germany; and plain, printed, painted, and embroidered cottons from India as imports to Britains colonies in North America. At various times throughout this period the colonists engaged themselves in weaving cloth for clothing and engaged the indigenous populations in trade for furs and skins.

Clothing was not socially neutral, however. What people wore was influenced by many more factors other than their cultural and religious backgrounds and the kinds of fabrics that were available to them. Dress was an immediate form of communication used to convey information about social, economic, and legal status; ethnicity; and religious affiliation. Society was stratified and hierarchical: appearance, including dress, was an outward and visible sign of a persons place in that society. And appearance was expected to be supported by behaviors, activities, occupations, environments, education, carriage, and manners appropriate to status.

Next page