A series of classic texts by revolutionaries in both thought and deed.

Each book includes an introduction by a major contemporary writer

illustrating how these figures continue to speak to readers today.

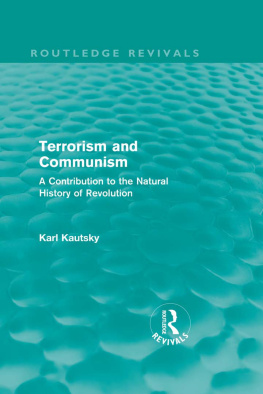

TERRORISM AND

COMMUNISM

A REPLY TO KARL KAUTSKY

LEON TROTSKY

FOREWORD BY SLAVOJ IEK

PREFACE BY H.N. BRAILSFORD

This edition published by Verso 2017

First published by Verso 2007

First published as Dictatorship vs Democracy by the Workers Party of America 1920

Foreword Slavoj iek 2007, 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-343-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-345-3 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-344-6 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Trotsky, Leon, 18791940, author. | Zizek, Slavoj.

Title: Terrorism and Communism : a reply to Karl Kautsky / Leon Trotsky ; foreword by Slavoj Zizek ; preface by H.N. Brailsford.

Other titles: Terrorizm i kommunizm. English

Description: New York : Verso, 2017. | Series: Revolutions | First published by Verso in 2007.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017024959 | ISBN 9781786633439 (paperback) | ISBN 9781786633453 (US e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Communism Russia. | Revolutions. | BISAC: PHILOSOPHY /

Political. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Ideologies / Communism & Socialism.

Classification: LCC HX36.K35 T813 2017 | DDC 335.430947 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017024959

Typeset in Bembo by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the UK by CPI Mackays, UK

CONTENTS

Trotskys Terrorism and Communism, or,

Despair and Utopia in the Turbulent Year of 1920

Karl Kraus, the Viennese cultural critic and chronicler (author, among other things, of the famous claim that psychoanalysis is itself the disease it tries to cure), knew of Trotsky from the latters sjour in Vienna before the First World War. One of the legends about Kraus is that, in the early 1920s, when he was told that Trotsky saved the October Revolution by organizing the Red Army, he exclaimed: Who would have expected that of Herr Bronstein from Caf Central! This remark relies on the transubstantiation in the style of the famous anecdote on Zhuang-Tze and the butterfly: it was not Trotsky, the great revolutionary, who, during his exile in Vienna, spent time in Caf Central; it was the gentle and loquacious Herr Bronstein from Caf Central who later become the dreaded Trotsky, the scourge of the counter-revolutionaries.

There are other figures of Herr Bronstein which enact a similar mystifying transubstantiation of Trotsky and thus stand in the way of properly understanding his importance. First, there is the gentrified image of Trotsky popularized today by the latter-day Trotskyists themselves: Trotsky the anti-bureaucratic libertarian critic of the Stalinist Thermidor, partisan of workers self-organization, supporter of psychoanalysis and modern art, friend of surrealists, etc. (and one should include in this etc. the brief love affair with Frida Kahlo) this is the domesticated figure that leads one not to be surprised that some of Bushs neocons are ex-Trotskyists (exemplary is here the fate of Partisan Review: it started in the 1930s as the voice of the Communist intellectuals and artists; then it became Trotskyist, then the organ of liberal Cold Warriors now it supports Bush in the War on Terror). This Trotsky almost makes one sympathetic to Stalins anti-Trotskyist wisdom.

Those critical of Trotsky invented another figure of Herr Bronstein: Trotsky as the wandering Jew of the permanent revolution who could not find peace in the routine post-revolutionary process of (re)constructing a new order. No wonder that, in the 1930s, even many conservatives looked favourably both upon the Stalinist cultural counterrevolution as well as upon the expulsion of Trotsky both were read as an abandonment of the earlier Jewish-international revolutionary spirit and as the return to Russian roots. Even such a critic of Bolshevism as Nikolai Berdaiev expressed in the 1940s, just before his death, a certain sympathy for Stalin, and considered returning to the USSR. Along these lines, Trotsky appears like a kind of Russian Che Guevara in contrast to Fidel: Fidel, the actual leader, supreme authority of the state, versus Che, the eternal revolutionary rebel who could not resign himself to just running a state. Is this not something like a Soviet Union in which Trotsky would not have been rejected as the arch-traitor? Imagine if, in the middle of the 1920s, Trotsky had emigrated and renounced Soviet citizenship in order to instigate permanent revolution around the world, and then had died soon afterwards after his death, Stalin would have dutifully elevated him into a cult

All this makes Terrorism and Communism, Trotskys reply to Karl Kautskys vicious attacks on the Bolsheviks, so important: it belies both these figures. Kautsky, who is today deservedly forgotten, was in the 1920s the minence grise of the German Social Democratic Party, by far the strongest Social Democratic party in the world, and the guardian of Marxist orthodoxy against both Bernsteinian revisionism and leftist extremism. Terrorism and Communism presents a Trotsky who knew how to be hard, to exercise terror, and a Trotsky fully ready to accept the task of reconstructing daily life.

There is nonetheless a third figure of Herr Bronstein, one which relies precisely on Terrorism and Communism: Trotsky the precursor of Stalin who, in 1920, already called for one-party rule, militarization of labour No wonder Terrorism and Communism is disowned even by many a Trotskyist, from Isaac Deutscher to Ernest Mandel (who characterized it as Trotskys worst book, his relapse into anti-democratic dictatorship). There are passages in Terrorism and Communism which effectively seem to point forwards to the Stalinist 1930s with their spirit of total industrial mobilization to drag Russia out of its backwardness. After Stalins death, a well-read copy of Terrorism and Communism was found among his private papers, full of handwritten notes which signalled Stalins enthusiastic approval what more does one need as a proof?

This is why Terrorism and Communism is Trotskys key book, his symptomal text which should on no account be politely ignored but, on the contrary, focused on. We leave to the canailles of cynical wisdom the dubious pleasure of dwelling on the (from the hindsight of todays perspective) all too obvious illusions of the book, starting with Trotskys reliance on the forthcoming West European revolution. One should not forget that this belief was shared by all Bolsheviks, Lenin included, who saw the survival of their power not as opening up the space for constructing socialism in one country, but as buying them a breathing space, surviving till relief arrived in the guise of the West European revolution that would release the pressure. The crucial problem lies elsewhere: the battle for Trotsky should be won on the very Stalinist terrain of terror and industrial mobilization: it is