Routledge Revivals

The Essential Trotsky

When Lenin died and the Russian Revolution began to devour its leaders, Trotsky survived longer than most as an exile in Mexico, until his assassination in 1940. The Essential Trotsky, first published in 1963, demonstrates the significance of this innovative and radical thinkers contribution to the Bolshevik success, the magnetism of his personality, and also a certain tragic heroism discernible throughout his life.

The History of the Russian Revolution to Brest-Litovsk was written immediately after the events it describes, when Trotsky was attending the negotiations that extracted Russia from the First World War; The Lessons of October, an answer to his opponents in 1924, matches Lenin in power of analysis; and Stalin Falsifies History, written in 1927, presents the beginning of the distorting process by which Stalin secured his position, and defeated a range of attitudes, many more benign than his own, towards the future of the Revolution. This is a fascinating reissue that will be of value to students with an interest in early twentieth-century Russia, the Russian Revolution and the writings of Trotsky more generally.

The Essential Trotsky

Leon Trotsky

First published in 1963

by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1963 George Allen & Unwin Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-01517-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-79455-6 (ebk)

Additional materials are available on the companion website at

http://www.routledge.com/books/series/Routledge_Revivals

LEON TROTSKY

THE ESSENTIAL TROTSKY

LONDON UNWIN BOOKS

First published in this edition 1963

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act no portion may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiry should be made to the publishers.

This edition George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1963

UNWIN BOOKS

George Allen & Unwin Ltd

Ruskin House, Museum Street

London, W.C.1.

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

in 9 on 10 pt. Plantin type

BY C. TINLING AND CO. LTD

LIVERPOOL, LONDON AND PRESCOT

CONTENTS

I. The History of the Russian

Revolution to Brest-Litovsk

THE facts of Trotskys life are pretty generally known. The son of a prosperous Jewish farmer in the Ukraine he was born in 1879. A brilliant schoolboy, ambitious and a bit of an egoist he owed much to the care of a liberal-minded educated uncle; he read widely and at sixteen wrote well; a devotee of the theatre it was art, literature and pure mathematics that attracted him; he thought of an academic career, a career which was not nearly profitable enough for his practical father yet more in accord with a Jewish tradition than that peasant father would admit. At the secondary school in Nikolaiev he first came in contact with the new revolutionary ideas which began to permeate the student world after the old Narodniks the party of enlightenment, assassination and reliance on the moujik had been discredited by failure. He took long to assimilate the new teachings of organization and reliance on the workers but in the end after a considerable intellectual struggle he became a Marxist. He graduated from the Nikolaiev college with first-class honours but his conversion put an end to dreams of an academic career. Now he was more concerned with politics than with mathematics. He did go to Odessa University. But once there he took the lead in founding a Socialist organization among the workers of that city; he edited and virtually wrote its clandestine mimeographed paper; he learned to speak in public as well as argue in private, and in the end was perhaps a greater orator than arguer. He was soon arrested and completed his political education in prison.

The turn of the century saw the revival in Russia of revolutionary activityassassinations, strikes, demonstrations. In exile in Siberia he worked out for himself much of what Plekhanov and Lenin were advocating from abroadthe need for an overall organization which implied on the one hand leaders and on the other loyal followers who would be led. In Siberia he was cut off from direct contact with the new leaders in Russia and in foreign parts. Nor could he write freely and to him writing was an essential part in the formation of his own thought. Literary articles were not so carefully scanned by the censor and a literary critic could slip a good deal of indirect advocacy. He was a good literary critic and the writing of criticism helped to form his style and prune of it of some at least of the romantic flamboyance that is inseparable from youthor was in these days. He began to learn two of the essentials for a revolutionary politician, clarity of expression and self-discipline.

Not until 1902 did he gain the contacts that he needed through the arrival in his place of exile of a file of Iskra, the paper of the exiles, Lenins Iskra. The realization that in his isolation he had reached the same conclusions as the Iskra-ites made Siberian exile intolerable. He escaped, reached Samara on a faked passport on which he had inscribed Trotsky as a cover namehe took it from a former jailerand found there an urgent message from Lenin to come to Iskras foreign headquarters. In October 1902 he joined Lenin and the Iskra in London.

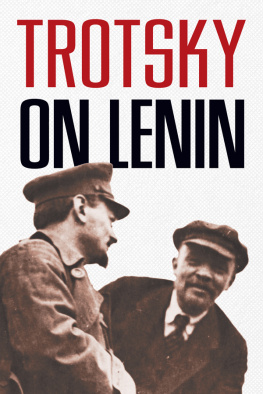

He did not know it then, but that meeting determined his life. The Social Democrats of whom Iskra was the organ were not united and even the Iskra group were as often as not at logger-heads. Neither Plekhanov nor Lenin were addicted to tolerance when it came to party questions; through the formers reputation and in the latters sheer intellectual competence on the matters at issue, each of them could justify a good deal of intolerance. They both taught Trotsky much, but while the ebullient, romantic Jew would accept tuition he would not accept control. When on the organizational issue the party split, Trotsky became neither a Menshevik nor a Bolshevik and argued fiercely with both; it was not until 1917 that he came wholeheartedly down on Lenins side and gave him an allegiance as between equals from which he never varied. What united them was less agreement on theory as agreement on action. They took opposite views on many points even practical political ones after that, but it was characteristic of both men that, despite the fierceness of old controversies and the language in which they were carried on, they never, once the moment for action arrived, allowed difference to become division.