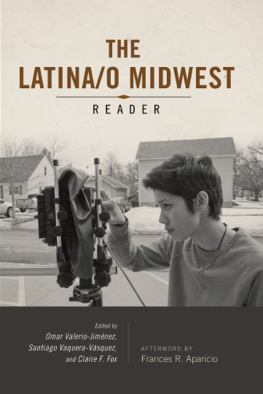

DE COLORES MEANS

ALL OF US

Latina Views for a

Multi-Colored Century

Elizabeth Martnez

This edition first published by Verso 2017

First published by South End Press 1998

Elizabeth Martinez 1998, 2017

Foreword Angela Y. Davis 1998, 2017

Introduction Karma R. Chvez 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-117-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663118-3 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78663-119-0 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Library of Congress Has Cataloged the First Edition as Follows:

Martinez, Elizabeth Sutherland, 1925

De colores means all of us: Latina views for a multi-colored century/by Elizabeth Martinez.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-89608-583-x (alk. Paper). ISBN 0-89608-584-8 (alk. Paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-896-08583-1

1. Pluralism (Social sciences)United States. 2. United StatesEthnic relations. 3. United StatesRace relations.

4. MinoritiesUnited StatesSocial conditions. 5. Mexican AmericansEthnic identity. 6. Mexican AmericansSocial conditions. 7. Mexican-American womenPolitical activity.

I. Title.

E184.A1M313 1998

305.800973dc21

98-6841

CIP

Printed in the US by Maple Press

For la juventud,

the youth, and their

revolutionary vision

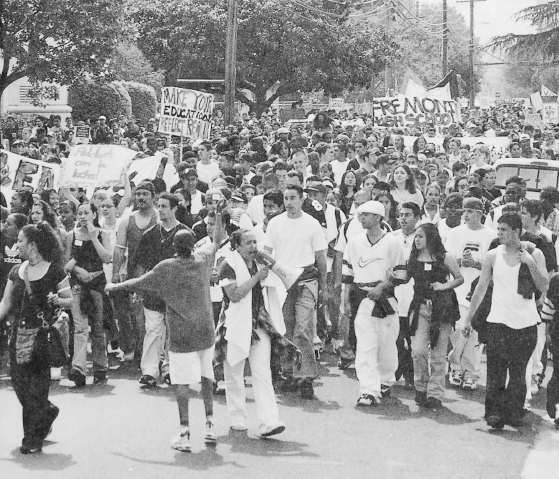

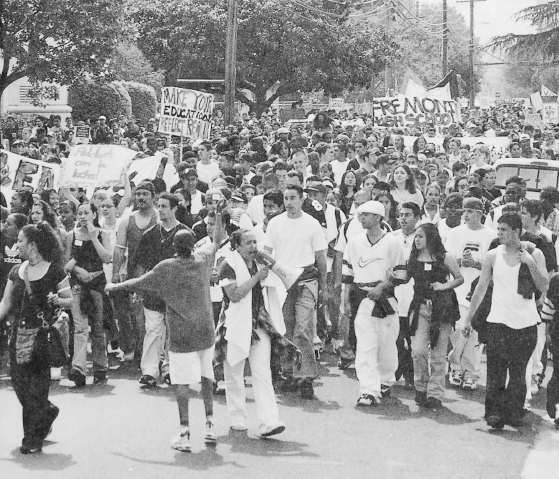

Walkout by 2,000 high school students for better schools. April 22, 1998. Concord, California

Photo: Kahlil Jacobs-Fantauzzi

About De Colores

The title of this book is taken from a traditional song that says:

De colores,

De colores se visten los campos en la primavera

De colores,

De colores son los pajaritos que vienen de afuera

De colores,

De colores es el arco iris que vemos lucir

Y por eso los grandes amores de muchos colores

Me gustan a mi

Here, with much poetic license, is a translation into English:

Many colors,

In spring the fields don many colors

Many colors,

The birds that come from afar have many colors

Many colors,

The lustrous rainbow that we see has many colors

And that is why the great loves of many colors

Are so pleasing to me

Contents

PART I:

SEEING MORE THAN BLACK AND WHITE

PART II:

NO HAY FRONTERAS: The Attack On Immigrant Rights

PART III:

FIGHTING FOR ECONOMIC AND ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

PART IV:

RACISM AND THE ATTACK ON MULTICULTURALISM

PART V:

WOMAN TALK: No Taco Belles Here

PART VI:

LA LUCHA CONTINUA: Youth In The Lead

INTRODUCTION TO THE 2017

EDITION

In the nearly twenty years that have passed between the dawn of 2017 and the original writing and publication of De Colores Means All of Us, movements and organizing in the settler colonial state most call the United States of America have been vibranthope, devastation, rage, and righteousness have characterized these first two decades of the twenty-first century. Veterans have stayed the course, new voices have emerged, and a spirit of justice continues to carry the energy of so many of us who, in myriad ways, fight the structures, institutions, and otherwise oppressive forces that face us. In these ways, the early twenty-first century is no different than the decades and centuries that preceded it, even as the particularities of this historical moment present new challenges.

In the nearly twenty years that have passed between the dawn of 2017 and the original writing and publication of De Colores Means All of Us, movements and organizing in the settler colonial state most call the United States of America have been vibranthope, devastation, rage, and righteousness have characterized these first two decades of the twenty-first century. Veterans have stayed the course, new voices have emerged, and a spirit of justice continues to carry the energy of so many of us who, in myriad ways, fight the structures, institutions, and otherwise oppressive forces that face us. In these ways, the early twenty-first century is no different than the decades and centuries that preceded it, even as the particularities of this historical moment present new challenges.

It is worth mentioning just some of these moments in recent movement historymoments in which communities of color have not only played roles, but have also often been the primary physical laborers, intellectual creators, and spiritual forces. The twentieth century faded with the so-called Battle of Seattle, where protestors from around the globe went to Seattle to challenge the World Trade Organization, corporate colonialism, and free trade policies. Mere months after the US Supreme Court gave George W. Bush the 2000 presidential election against Al Gore, the attacks of September 11, 2001 animated the BushCheney war machine. The so-called War on Terror catalyzed old and new anti-war protestors, who continue to challenge US actions, first in Afghanistan, then in Iraq, then under Obama and now Trump, in other parts of the region.

While anti-war efforts waged on, in late 2005, Wisconsin Republican congressman Jim Sensenbrenner proposed HR 4437, which passed the House but failed in the Senate and would have required, among other provisions, the construction of 700 miles of border fence, aggressive deportation practices, and criminalization of citizens and legal residents who house or otherwise harbor undocumented folks. Largely Latinx, Asian and immigrant groups took to the streets throughout the spring of 2006 with some of the largest protests since the civil rights era to challenge anti-immigrant actions and laws. Less than two years later, when then-candidate Barack Obama announced his support for the DREAM Act, undocumented youth who had cut their teeth on activism in the 2006 protests catalyzed a national movement to advocate for the DREAM Act and comprehensive immigration reform. Although these actions fell short of their primary objectives, they did prompt Obama to pass an executive order in 2012 called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which gave select undocumented youth a slight reprieve from being targeted for deportation and granted access to a legal work permit.

Following actions by people in the Middle East and North Africa against authoritarianism, joblessness, and corruption, among other factors, that led to what some call the Arab Spring of late 2010, in 2011 tens of thousands of protestors in Wisconsin took to the streets for months to challenge laws passed by the newly elected Republican governor Scott Walker and the new Republican state legislature that stripped public unions of collective bargaining rights and gutted the historic University of Wisconsin system. Later that year, protestors set up camp in Zuccotti Park in New York Citys financial district to challenge wealth inequality and corruption on Wall Street. Occupy and in some cases (Un)Occupy camps were set up around the country in strategic locations to challenge the rule of the 1% and to provide temporary shelter and support for local homeless people.

Although police and vigilante violence against black, brown, indigenous, and immigrant communities is as old as the republic itself, the February 2012 killing of eighteen-year-old black youth Trayvon Martin by neighborhood vigilante George Zimmerman in Florida catalyzed a national movement that is still in full swing. Deemed by Opal Tometi, Alicia Garza, and Patrisse Cullors, Black Lives Matter, in its national and local iterations, this movementled largely by black queers, trans folks, and/or womenchallenges state violence against black communities and seeks community-based responses to oppression. Following the 2014 police killing of eighteen-year-old black youth Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, the movement was further stoked as the Ferguson Rebellion became a meeting place for national groups to support one another and be trained. These years of efforts have resulted in a Movement for Black Lives vision statement and the development of black youth leadership around the United States. Late 2016 was characterized not just by the brutal presidential election, but by the stand off at the lands of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in North Dakota, as indigenous leaders and thousands of allies set up camp to protest the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline, which would have run under sacred sites and come dangerously close to the tribes water supply. While each of these uprisings has morphed in different ways, the principles they each represent continue beyond the immediate crisis points that made, or

In the nearly twenty years that have passed between the dawn of 2017 and the original writing and publication of De Colores Means All of Us, movements and organizing in the settler colonial state most call the United States of America have been vibranthope, devastation, rage, and righteousness have characterized these first two decades of the twenty-first century. Veterans have stayed the course, new voices have emerged, and a spirit of justice continues to carry the energy of so many of us who, in myriad ways, fight the structures, institutions, and otherwise oppressive forces that face us. In these ways, the early twenty-first century is no different than the decades and centuries that preceded it, even as the particularities of this historical moment present new challenges.

In the nearly twenty years that have passed between the dawn of 2017 and the original writing and publication of De Colores Means All of Us, movements and organizing in the settler colonial state most call the United States of America have been vibranthope, devastation, rage, and righteousness have characterized these first two decades of the twenty-first century. Veterans have stayed the course, new voices have emerged, and a spirit of justice continues to carry the energy of so many of us who, in myriad ways, fight the structures, institutions, and otherwise oppressive forces that face us. In these ways, the early twenty-first century is no different than the decades and centuries that preceded it, even as the particularities of this historical moment present new challenges.