Bruno Maes

THE DAWN OF EURASIA

On the Trail of the New World Order

ALLEN LANE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Allen Lane is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

First published 2018

Copyright Bruno Maes, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design: Richard Green

ISBN: 978-0-241-30926-1

To the Lady of Suggestions

The breeze at dawn has secrets to tell you.

Rumi

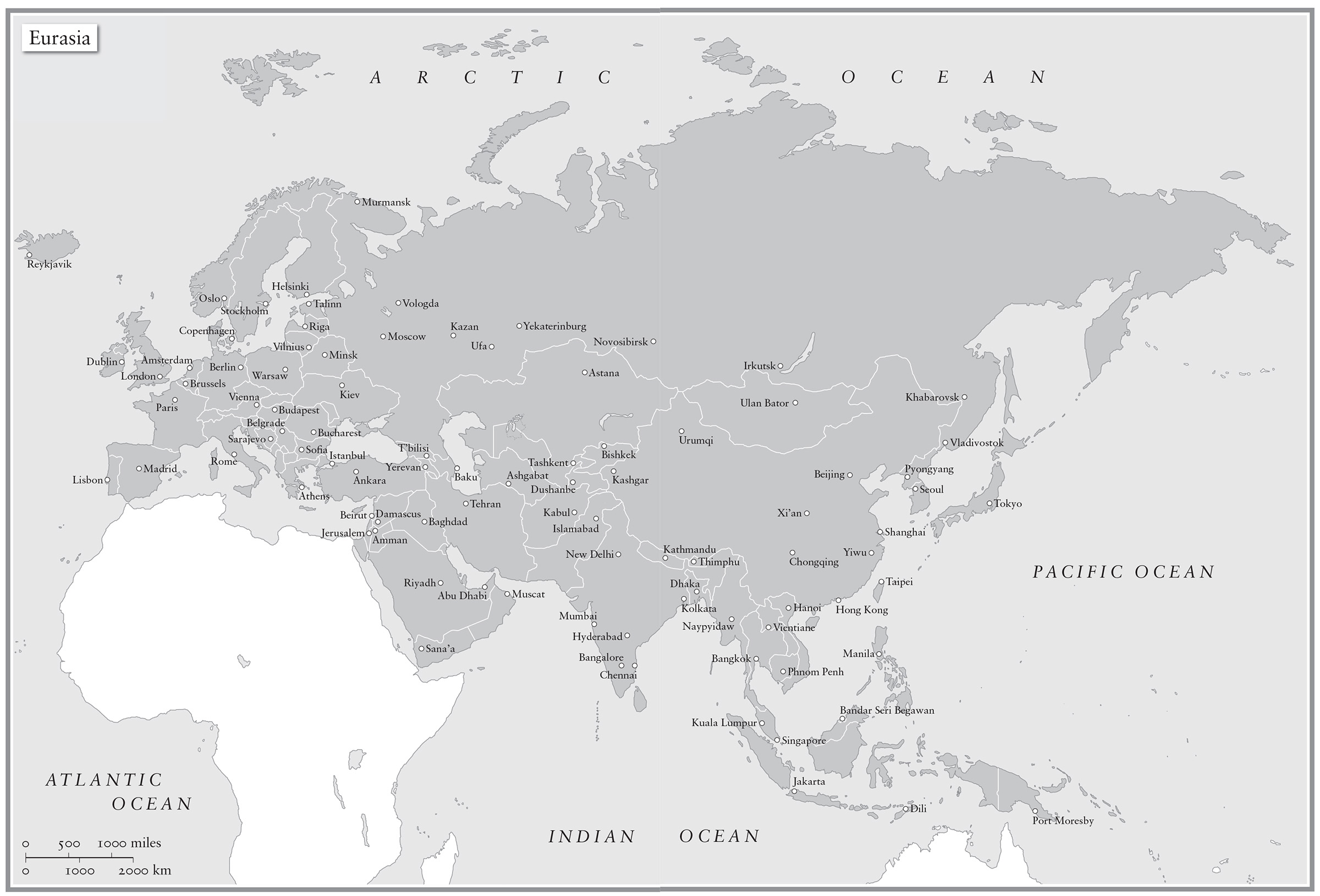

Preface

At the end of 2015, I left on what was to become a six-month journey along the historical and cultural borders between Europe and Asia. During the previous two years, my work in the Portuguese government, where I was the Secretary of State in charge of European Affairs, had constantly pulled me towards these borderlands, sometimes by personal predilection, most often by necessity. It must mean something important when this happens to the country sitting on the westernmost tip of Europe. Seeing that so many of the most urgent questions affecting the European Union had to do with the interactions between the two continents and how the management of these interactions called for an enlarged perspective, I started to suspect history was increasingly leading us to a world where the border between Europe and Asia would disappear. The bookshops were full of books about Russia (usually its dangers), China (usually its miracles) and the European Union (usually its crises), but they considered them in isolation. I decided to investigate what you could learn about Russia, China and Europe if you considered them as parts of the same system. There was an obvious word to describe this system: Eurasia. It is a relatively new word, first used in the nominal form by the Austrian geologist Eduard Suess in 1885. The notion that Europe and Asia should be thought of as a single whole has been the precinct of geologists and biologists confronting the fact that a border between the two continents is an obstacle to scientific understanding. As the great German explorer and scientist Alexander von Humboldt put it in 1843, in the natural sciences one must start with the connectivity of the great divisions of the old world. But why only in the natural sciences? Why not in history, politics and the arts? That was how the idea for this book first arose.

My Eurasian journey was to follow two simple rules. First, no flights were allowed, even if only to connect two points or to overcome a logistical difficulty. Second, there would be no plans beyond the current week. I had no idea how long the journey would take. Route and calendar were still to be determined when I landed in Astrakhan in Russia on 15 December. I picked Astrakhan for the starting point because this was the historical gateway to the Caucasus, which topped my list of transition areas where the shape of the future supercontinent may already be prefigured. Astrakhan, a once mighty city, now almost forgotten by the rest of the world, was in more than one sense an excellent beginning. I had not yet decided on the end.

During the first month, I roamed around in the Caucasus, eventually crossing the mountain range via the traditional Georgian military highway. From Georgia I travelled to Armenia and then Iran before turning west to the Turkish Black Sea coast. From Trabzon I headed east, all the way to Baku in Azerbaijan, from where I boarded a cargo ship, across the Caspian and into the Central Asian segment of my trip. Merv, Bukhara, Termez, Samarkand. Having reached Andijan in the Fergana Valley, already close to the Chinese border, one could be sure to have left Europe behind, but then I wanted to see how this same transition route would look from the other side. I headed north to Kazakhstan and Siberia, travelling to Vladivostok by way of Lake Baikal and entering China on its easternmost point. I then retraced my steps to Central Asia, all the way to the new landmark city of Khorgas, which I had seen from the distance while standing on the Kazakhstan border two or three months earlier. In all, the journey took exactly six months. Since I boarded a plane from Ili to Beijing on 15 June 2016, the first rule dictated that, even though I would continue to travel while doing research for the book, the Eurasian journey was effectively over. From Astrakhan to Khorgas by the longest possible route.

We are living in a golden age of travelling. Recent technology, like digital maps and translators, together with all the constantly updated information on the internet, eliminate almost all sources of hassle or danger, but at the same time the destructive impact of tourism remains limited to the same popular spots, leaving much of the world either as it was centuries ago or as it has become as a result of modernization, and both states are equally genuine and important. Travel has never been easier, but travel writing will probably not survive in a world where everyone can be anywhere on the map in less than twenty-four hours. Most travelogues have tried to get around this problem by focusing on form and becoming their own genre of fiction. I do something different in this book. I use travel to provide an injection of reality to political, economic and historical analyses.

In January 2017 I moved to London, where I would be advising hedge funds and tech companies on political strategy. The world in which they operate is the new Eurasian world described in this book. Hedge funds attempting to take advantage of mergers and acquisitions are actively tracking the inflow of Chinese capital to Europe, but know that this works according to very different rules to those they are used to, and want to understand the political dynamics by which two different systems of rules clash and combine. Tech companies are actively trying to enter the Russian market, for which they are particularly suited, but doing so at a time of geopolitical conflict between the West and Russia means that every movement has to be seen from two opposite perspectives at once, and sometimes these two perspectives create endless games of mirrors. There is the obvious need to think globally, but the differences are more interesting than the similarities. Businesses know this better than politicians, writers or artists.

One of the main purposes of this book is to show how the world is just as it has always been a wondrous and strange place. If we keep our eyes open, it is easy, at almost every turn of the road, to enter a world of pure imagination, where our habitual way of looking and thinking suddenly fails us. That is why, just as travel can help ground analysis in the real world, so is analysis at some level of reflection indispensable to guide us through the many different ways of seeing the world. Thoughts without travels are empty; travels without concepts are blind.