TO RULE EURASIAS WAVES

GEOFFREY F. GRESH

To Rule Eurasias Waves

THE NEW GREAT POWER COMPETITION AT SEA

Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund.

Copyright 2020 by Geoffrey F. Gresh. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

The views expressed in this book are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the National Defense University, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Maps by Bill Nelson.

Set in Times Roman type by Integrated Publishing Solutions,Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932817

ISBN 978-0-300-23484-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

For Leigh, Audrey, Joan, and Gloria

CONTENTS

North Sea and Baltic Sea

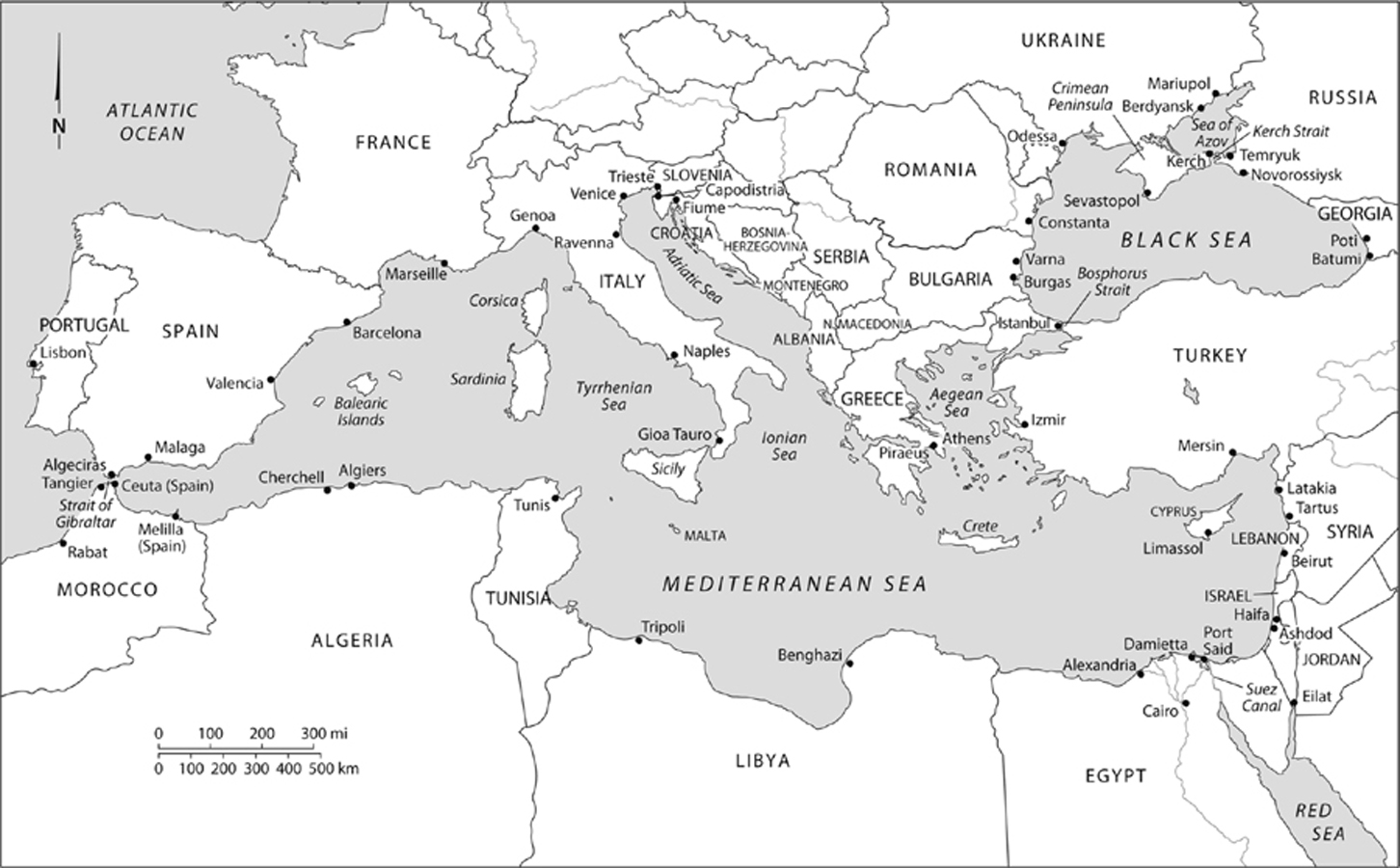

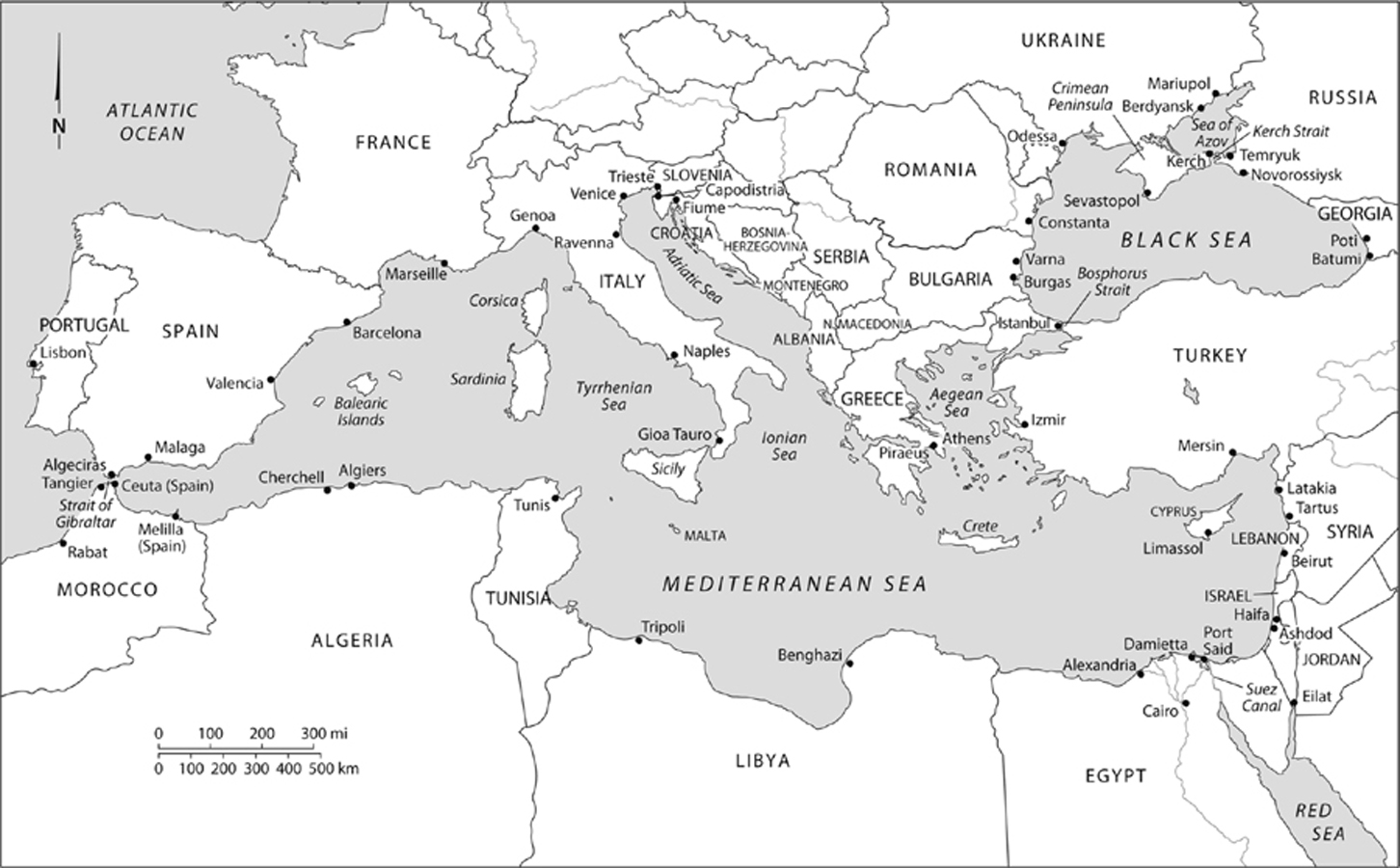

Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea

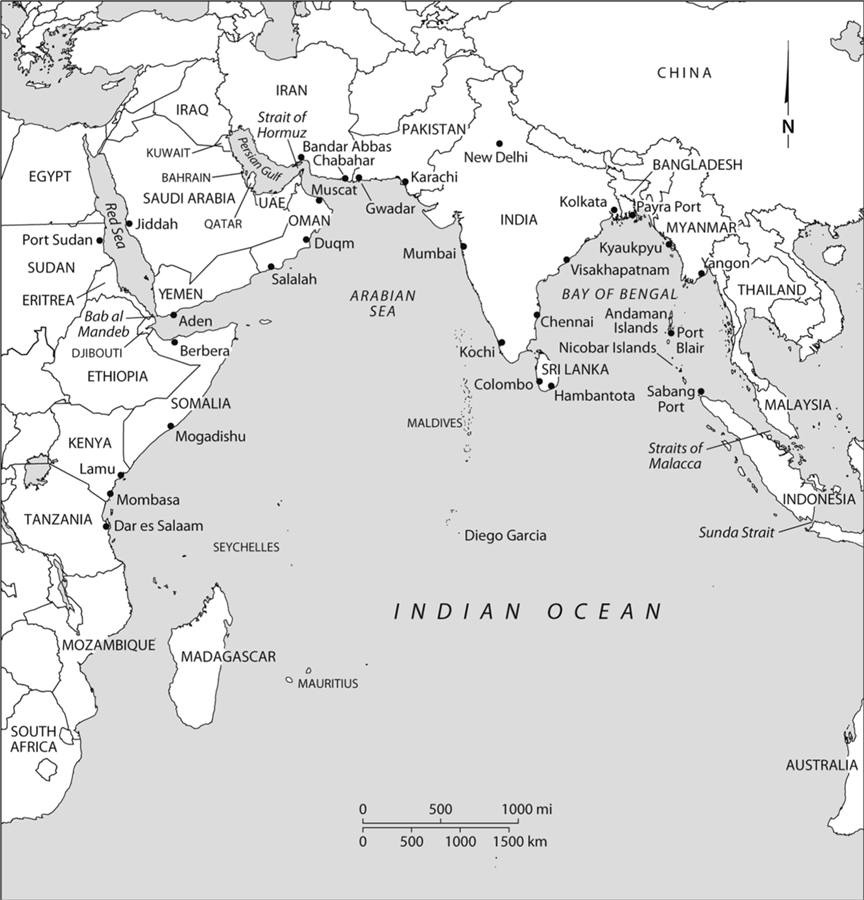

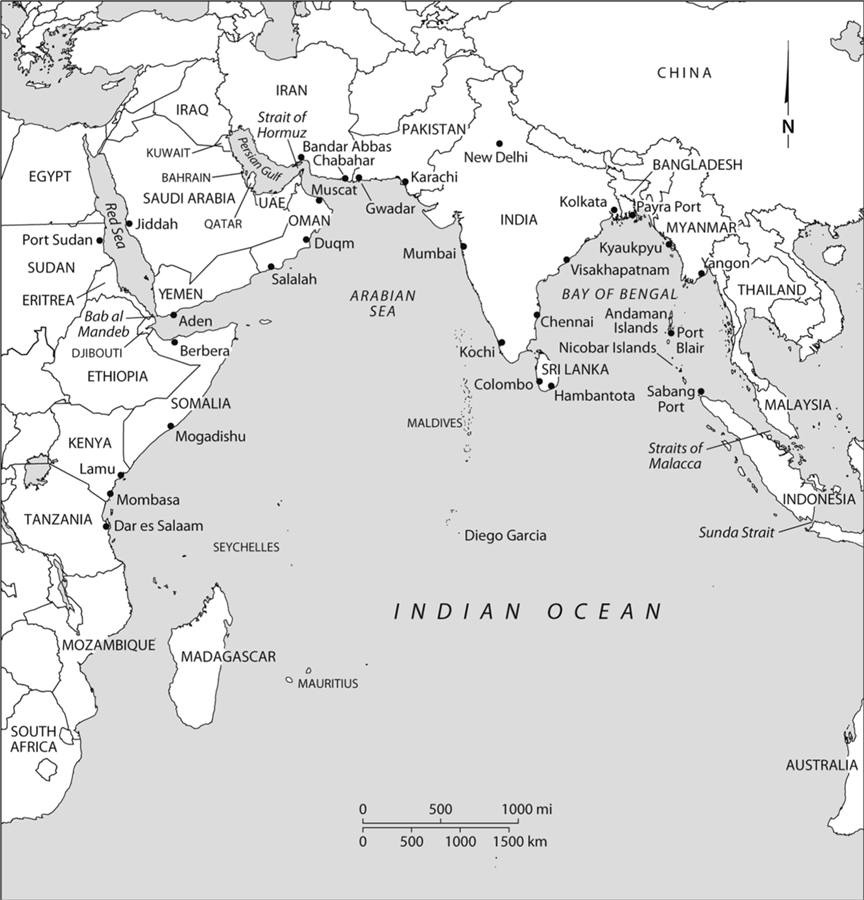

Indian Ocean

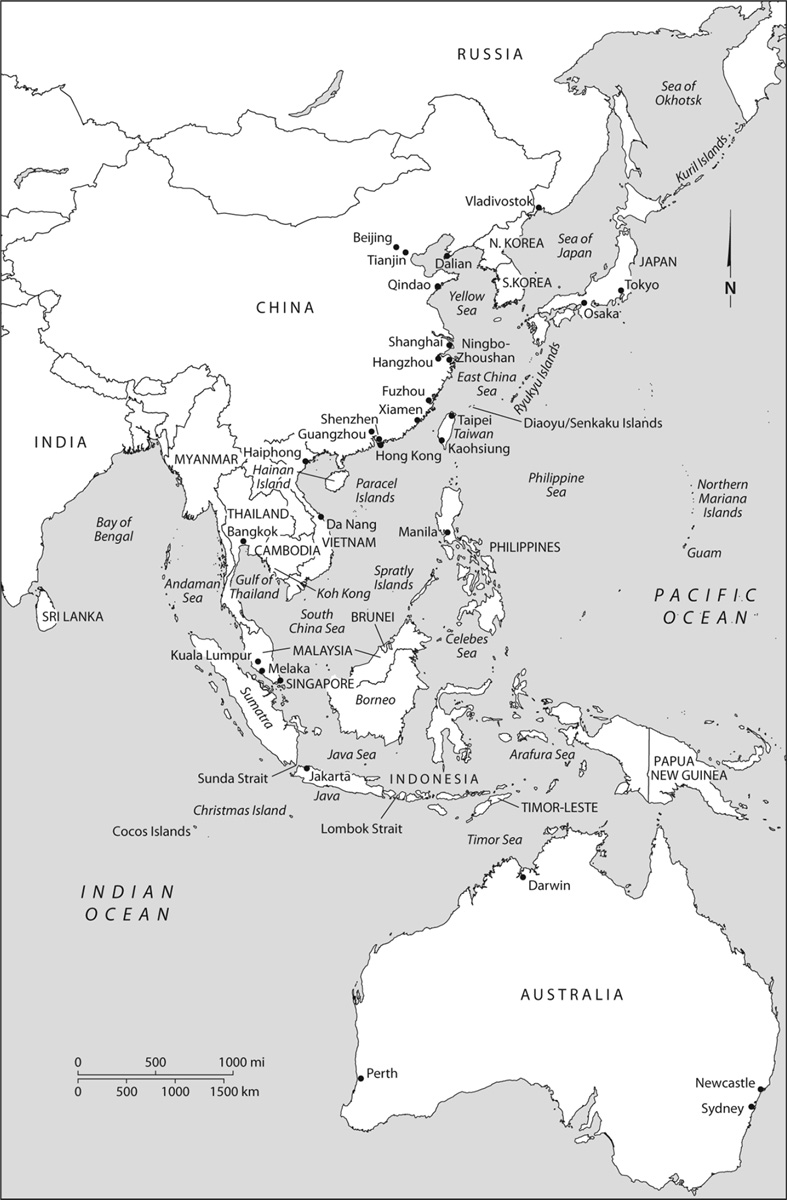

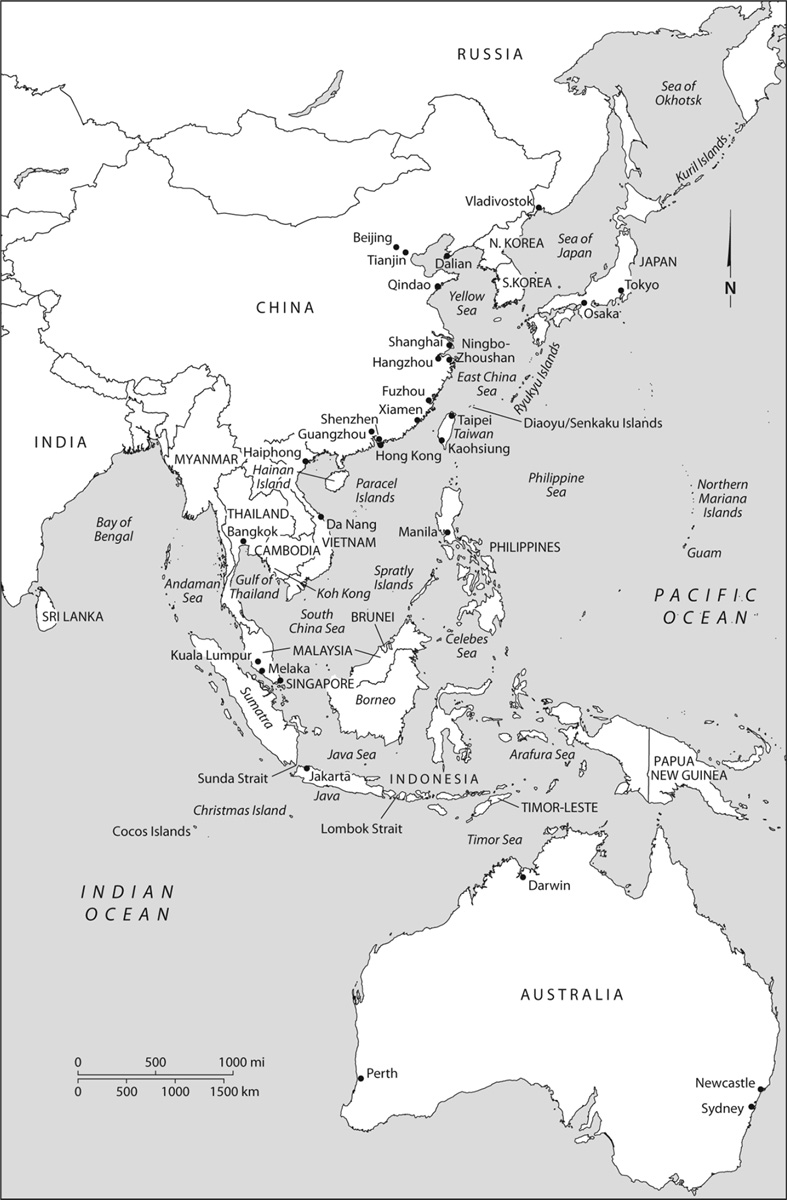

East Asia

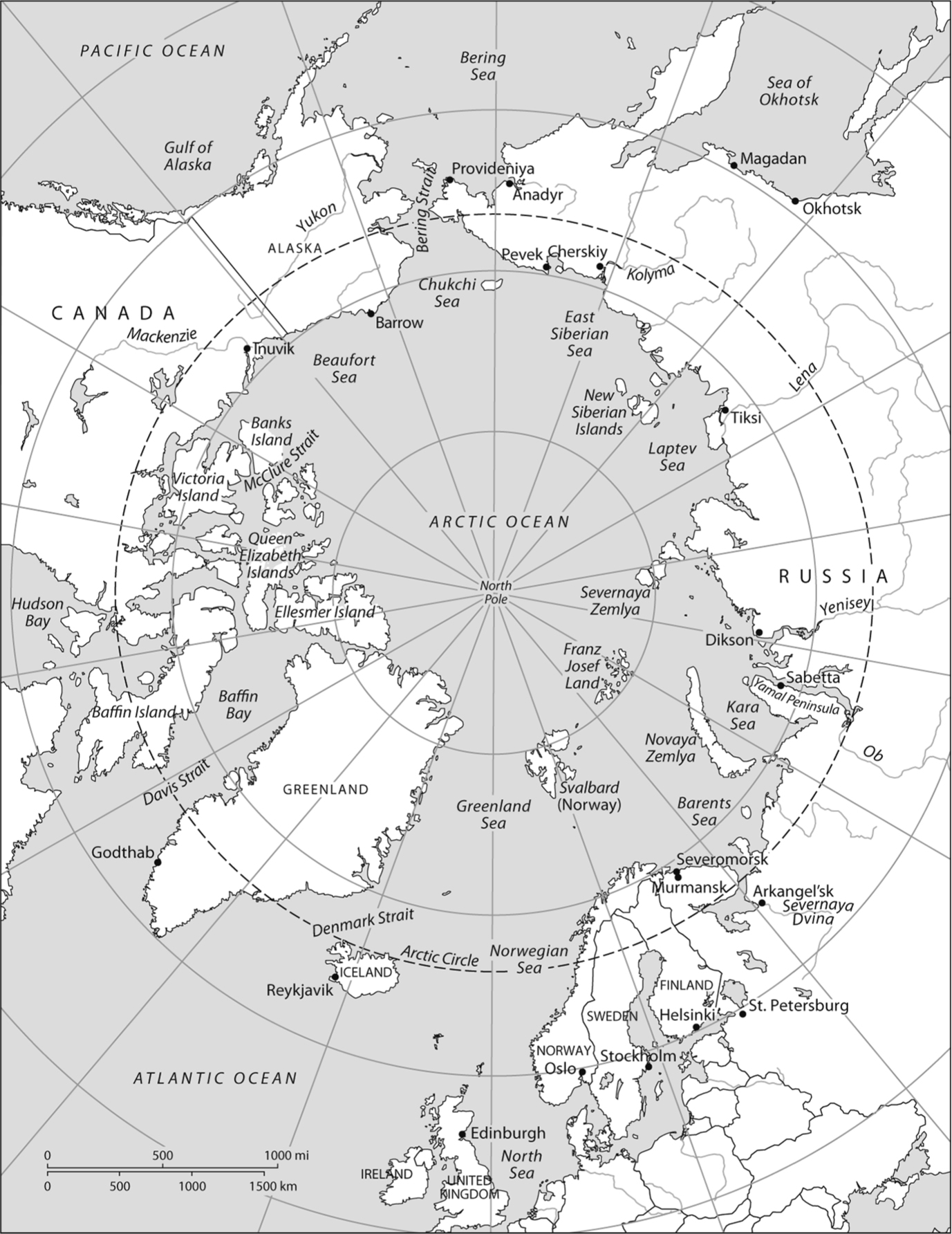

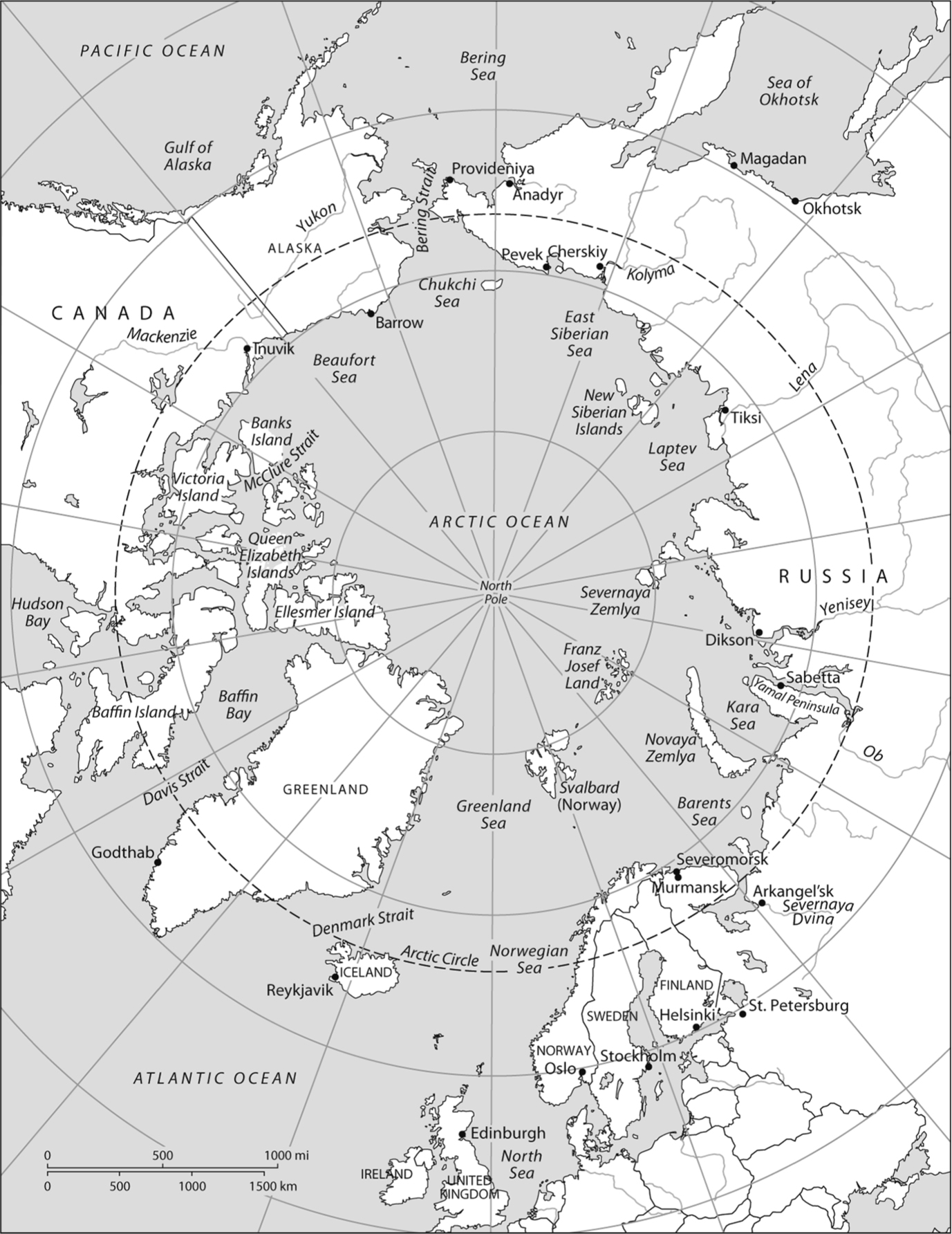

Arctic Ocean

1

Eurasias New Great Power Competition at Sea

Who controls the rimland rules Eurasia;

who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.

Nicholas John Spykman

COMPETITION AT SEA HAS BEEN WRITTEN about since the days of ancient Greece. To rule the seas through maritime commerce or other means remains significant for all great powers today, but the real competition that has emerged in recent years is taking place across maritime Eurasia between the continents main rivalsChina, Russia, and Indiaas they vie to achieve great power status and to expand beyond their regional seas. This rising competition will dominate and shape the upcoming century as each power increases its geoeconomic, geopolitical, and naval embrace of maritime Eurasia from the Baltic, Black, and Mediterranean Seas to the Indian Ocean, Pacific Asia, and the Arctic.

Maritime Eurasia has long been the focus of renowned strategists and historians. But what Mahan, the geographer Nicholas Spykman, and others never imagined was the melting of the Arctic, the subsequent growing unification of maritime Eurasias disparate regions, and the emerging competition between Eurasias land powers at sea. Today, more than 90 percent of the worlds goods transit the sea, bringing into relief the continued importance of the stability and security of the global commons. As China, Russia, and India grow their geoeconomic interests and investments across maritime Eurasia, securing them, along with the sea lanes of communication, will become ever more critical.

For the near term, the United States will remain as a global superpower, especially in maritime Eurasia, but U.S. preeminence and the postWorld War II order that has long been dominated by the United States and the West are being challenged increasingly by China, Russia, and India. Certainly, along with the United States, other maritime powers such as Japan, South Korea, France, Great Britain, and Australia, among others, play important roles in this larger, albeit shifting, dynamic of maritime Eurasia, but they are not the main focus here because they have not undergone the same rapid maritime geoeconomic and geostrategic development in recent years compared to Eurasias three continental powers. Japan in particular has made noticeable leaps with the expansion of its Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) in locations such as Djibouti, but as one observer asserted recently, The MSDF is still essentially a defensively oriented force, and one that is mostly channeled through the U.S.-Japan alliance.

Today, the world order appears to be shifting increasingly away from one largely defined by the West toward a new one where Eurasias emerging continental powers play a more significant and influential role, contributing paradoxically to greater insecurity. Even though China still lags behind the United States in defense spending, Chinas current defense budget exceeds those of its primary regional neighbors combined, including Japan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Much of Chinas increased defense spending is translating into more focus on maritime security and power projection capabilities along Eurasias sea lanes of communication and other vital waterways. Eurasias vast maritime regions, for example, include some of the worlds most important strategicmaritime

Across maritime Eurasia, geoeconomics and security are two of several primary drivers pushing China, Russia, and India and their ever-increasing seaward tilt and blossoming maritime competition. China was recently named as the worlds largest trading partner, surpassing the United States with about $4 billion in annual trade volume. Some estimates also predict that China will dominate seventeen of the worlds top twenty-five bilateral trade avenues. The 2013 launch of its One Belt, One Road or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and Maritime Silk Road (MSR) aligns with this larger dynamic that sees Chinas geoeconomic and security interests increasingly interwoven owing to mounting maritime and global trade. Between 2003 and 2014, for example, Chinese international trade multiplied significantly, growing from $851 billion to more than $4.16 trillion. China also views peace in its peripheral territories and maritime waterways as critical for domestic harmony and thus its future development. This is why China is concerned about preventing or mitigating the undue influence of external powers, especially those trying to undermine or block its BRI projects. The BRI is indeed a risky endeavor because it is an agglomeration of many competing interests that will be hard to manage toward one singular strategic goal, as some critics argue. But even moderate success rates across the BRI and MSR could bring China significant geoeconomic and geostrategic victories as it seeks to alter a U.S.-led world order.

Indias burgeoning embrace of the sea is part of a similar natural trajectory as China and aligns with Eurasias larger growing maritime trade and security trends. The dilemma for India is twofold. First, it relies on the sea for 95 percent of its trade by volume, or an estimated 10 percent of its GDP. Second, it must also contend with the fact that, from a trade perspective, China has surpassed India throughout the Indian Ocean region. In 2012, China was the largest trading partner with Bangladesh and Pakistan and the second-largest partner to Sri Lanka. Indias current top trading partner is the United Arab Emirates to its west, but to the east an estimated 55 percent of Indian trade traverses the South China Sea, making it further vulnerable to Chinas rise. India recently teamed up with Japan to announce the Freedom Corridor in direct response to Chinas Belt and Road Initiative. Nevertheless, China is currently Indias second-largest trader, growing steadily from $1.5 billion in 2001 to $60 billion in 2016, further complicating the maritime flows to and from India in the event of a South China Sea conflict.

Next page