First published by Verso 2014

The collection Verso 2014

Introduction translation David Broder 2014

Nadyas letters translation Ian Dreiblatt 2014

Slavojs letters Slavoj iek 2014

The True Blasphemy first published by chtodelat news 2012

Slavoj iek 2012, 2014

Why I Am Going on Hunger Strike first published by n+1 2013

Translation Bela Shayevich and Thomas Campbell 2013, 2014

Nadyas August 23 letter and Slavojs August 26 letter first

published by mark-feygin.livejournal.com

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-773-4 (PB)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-774-1 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-775-8 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

Contents

Introduction

by Michel Eltchaninoff

The True Blasphemy: On the Pussy Riot Sentencing

by Slavoj iek

Why I Am Going on Hunger Strike: An Open Letter

by Nadya Tolokonnikova

All of our activity is a quest for miracles

Nadya to Slavoj, August 23, 2012

Ignore all who pity you as punk provocateurs

Slavoj to Nadya, August 26, 2012

It is so important that you persist

Slavoj to Nadya, January 2, 2013

We count ourselves among those rebels who court storms

Nadya to Slavoj, February 23, 2013

Is our position utopian?

Slavoj to Nadya, April 4, 2013

I write you from a Special Economic Zone

Nadya to Slavoj, April 16, 2013

Beneath the dynamics of your acts, there is inner stability

Slavoj to Nadya, June 10, 2013

As I serve my deuce in lockdown

Nadya to Slavoj, July 13, 2013

I would like to conclude with a provocation

Slavoj to Nadya, December 12, 2013

When you put on a mask, you leave your own time

Nadya to Slavoj, March 11, 2014

A new and much more risky heroism will be needed

Slavoj to Nadya, March 18, 2014

Introduction

At around 11 a.m. on February 21, 2012, an event unheard of in contemporary Russia played out in the countrys largest and most famous Orthodox church. The monumental Cathedral of Christ the Savior stands out in the skyline not far from the Kremlin, on the bank of the river Moskva. Constructed in the nineteenth century to commemorate the victory over Napoleon, the ultimate symbol of Tsarist power and seat of the Moscow Patriarchate, it was destroyed by the Soviet authorities and then rebuilt in the 1990s to mark the rebirth of Christianity in Russia after decades of official atheism. It was consecrated in 2000, at the very moment of Vladimir Putins accession to the presidency. But for many intellectuals it is a place which equally symbolizes the ostentatious pomp of an ecclesiastical hierarchy sporting expensive watches and luxury cars, who support the Kremlin leadership without fail while providing it with an ideological basis founded on traditional values and the boundless exaltation of Holy Russia. To launch an attack here is to hit at the very heartmetaphorical, but also very realof contemporary Russian power.

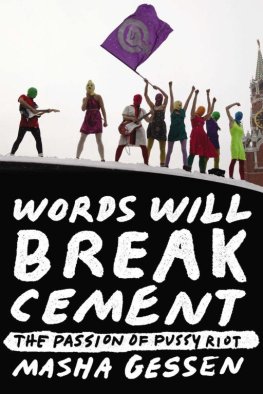

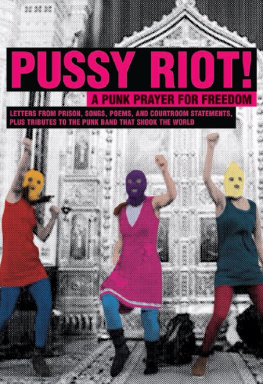

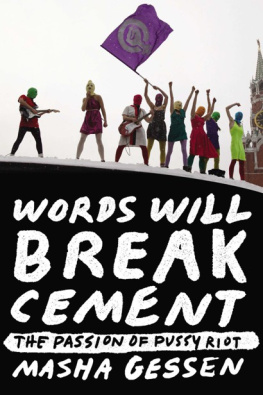

There is no service, this particular Tuesday morning. The immense space is very calm. Five young women pass the security checks without hindrance. They rapidly head over to the raised platform in front of the altar, reserved for the reading of sacred texts by the clergy. They slip on red, blue, orange, yellow, and violet balaclavas. They take off their coats, revealing their brightly colored dresses and tights. The female maintenance staff start to panic and call security. One security guard hurries across, tackles a young woman holding a guitar and pulls her away. He returns to grab hold of a loudspeaker. Church employees attempt to intercept the other four. But they have already begun their twenty-verse punk prayer, whose refrain is Virgin Mary, Mother of God, Banish Putin. Their song robustly denounces the corruption of todays Russian Church, its ultra-conservative ideology (Dont upset His Saintship ladies / Stick to making love and babies), the KGB past of Moscows Patriarch Cyril and his unconditional support for Vladimir Putins repressive policies (Patriarch Gundyaev believes in Putin / Better believe in God, you vermin!). The punks, kneeling and crossing themselves dramatically, conclude with the plea: Join our protest, Holy Virgin. The whole performance lasts a few dozen seconds at most, before the women file out of the church, accompanied by the ten people who had come to film and assist them.

As the first photos and videos circulated and began to spread around the world, three members of the group were arrested, placed under provisional detention, and charged with hooliganism (Article 213 of the penal code). Nadezhda Tolokonnikova (born in 1989), Maria Alyokhina (born in 1988), and Yekaterina Samutsevich (born in 1982) each faced up to seven years in prison.

This was not their first provocation. The hooded female punk group had emerged out of a radical contemporary art collective set up a few years earlier, in 2007, under the name Voina (War), initiated by Oleg Vorotnikov and Natalia Sokol. Nadya Tolokonnikova and her husband Piotr Verzilov were also members. Vorotnikov, Sokol, Tolokonnikova and Verzilov were students at the philosophy faculty of the prestigious Moscow State University, and were joined in the collective by other young people from St. Petersburg. Inspired by the actions staged by Russian artists like Alexander Brener and Oleg Kulik, the group began to organize provocative performances in public places. In February 2008, several couples, including the then-pregnant Nadya and Piotr, were photographed having sex in a hall of the Moscow Biological Museum. In June 2010, a giant painted phallus appeared on a bridge facing the FSB building in St. Petersburg, to the astonishment of passers-by. Combining contemporary art with political action, the collective quickly became one of the spearheads of artistic opposition to the Putin regime. In 2011, a number of its members, including Nadya Tolokonnikova and Katya Samutsevich, formed Pussy Riot.

At the end of that same year, the situation became increasingly troubling for the Russian leadership. On September 26, 2011, Dmitry Medvedevthen president and nearing the end of his termannounced that he would be handing power back to Vladimir Putin. Having been president from 2000 to 2008, Putin had had to, in effect, lend his protg the presidency for four years. He could now return as the head of the country for two six-year termsuntil 2024. All Vladimir Putin now had to do was make sure he won the election. Parts of Russian society were shocked by these far-from-democratic shenanigans, and had little love for a regime that appears to be lasting longer than did that of Leonid Brezhnev. The anger exploded after December 4, 2011, following parliamentary elections that handed victory to the Kremlin-controlled United Russia Party as a result of massive, and crude, electoral fraud. Street demonstrations in the larger towns and cities rallied tens, even hundreds of thousands of people. There had been no equivalent protests since the era of Perestroika. Pussy Riot participated enthusiastically, taking all sorts of risks. On January 20, 2012, eight group members performed a song mocking candidate Putin in the middle of Red Square, facing the Kremlin, the sacred site of political power. On February 21 they broke new ground by targeting the absolute taboo: the Russian Church hierarchys support for Kremlin policy.