HARRY BROWNE is a lecturer in the School of Creative Arts and Media at Dublin Institute of Technology. His journalism has appeared in CounterPunch, the Dublin Review and many Irish newspapers. Born in Italy and raised in the United States, he has lived in Ireland since the mid-1980s. His previous book is Hammered by the Irish: How the Pitstop Ploughshares Disabled a US War-Plane With Irelands Blessing.

COUNTERBLASTS is a series of short, polemical titles that aims to revive a tradition inaugurated by Puritan and Leveller pamphleteers in the seventeenth century, when, in the words of one of their number, Gerard Winstanley, the old world was running up like parchment in the fire. From 1640 to 1663, a leading bookseller and publisher, George Thomason, recorded that his collection alone contained over twenty thousand pamphlets. Such polemics reappeared both before and during the French, Russian, Chinese and Cuban revolutions of the last century.

In a period where politicians, media barons and their ideological hirelings rarely challenge the basis of existing society, it is time to revive the tradition. Versos Counterblasts will challenge the apologists of Empire and Capital.

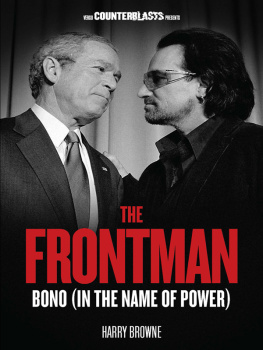

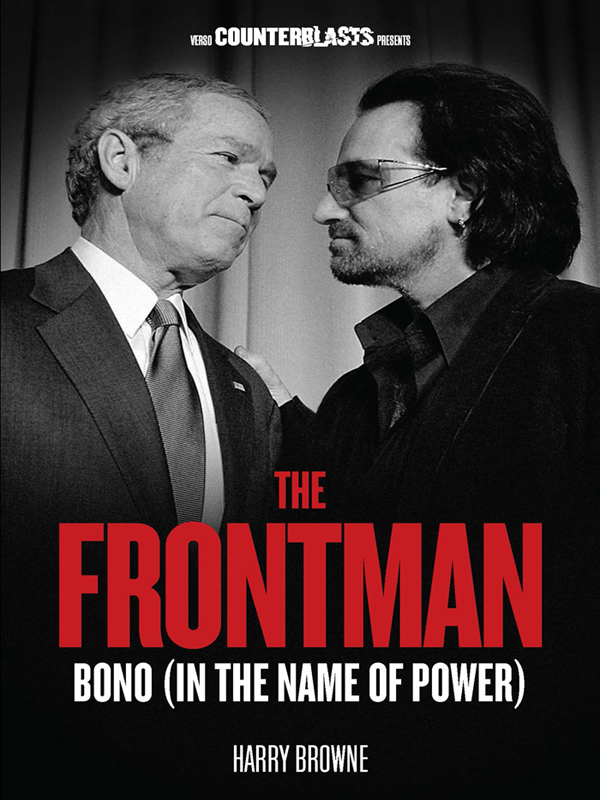

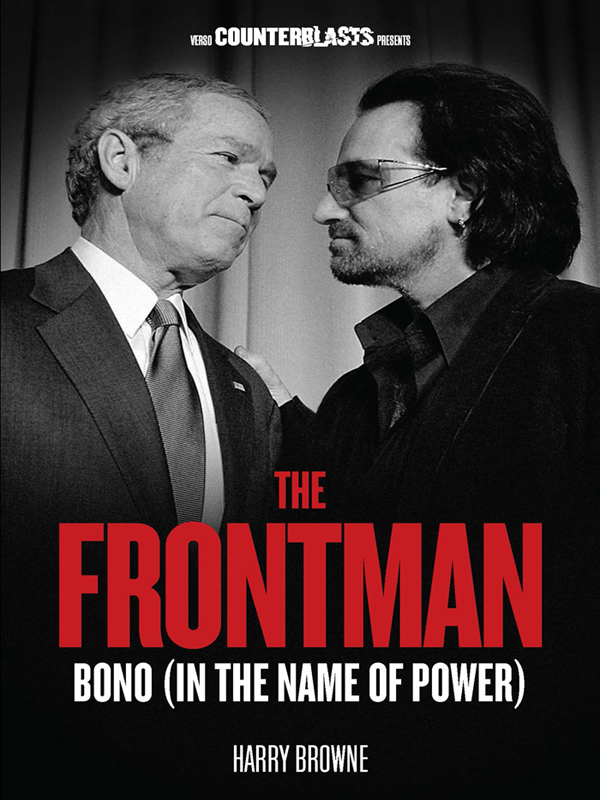

The Frontman:

Bono (In the Name of Power)

Harry Browne

First published by Verso 2013

Harry Browne 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Lyrics to Flights of Earls, composed by Liam Reilly, used by permission of Bardis Music Co. Ltd

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN: 978-1-781-68332-3 (e-book)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Minion Pro by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the US by Maple Vail

CONTENTS

Celebrity philanthropy comes in many guises, but perhaps no single figure better encapsulates its delusions, pretensions and misdirections than does the lead singer of rock band U2, Paul Hewson, aka Bono.

Thats because Bono is more than a mere giver of charity indeed, his fame in this realm has nothing to do with the spending of his own considerable fortune on the needs of the poor. He is, instead, an advocate, and as such has become a symbol of the essentially benign character of the Wests rich elite, ever ready to help the worlds poor just waiting for a little encouragement, and a few good ideas, to eliminate hunger and poverty forever. This makes him an ideal frontman for a system of imperial exploitation and war whose depredations and depravity remain as savage as ever.

Bonos own description of what he does for a living is travelling salesman, latest in a line:

A lot of our family are traveling salesmen. And of course that is what I have become! I am very much a traveling salesman. And that, if you really want to know, is how I see myself. I sell songs from door to door, from town to town. I sell melodies and words. And for me, in my political work, I sell ideas. In the commercial world that Im entering into, Im also selling ideas. So I see myself in a long line of family sales people.1

He has certainly been a more-than-competent seller of his musical work, and of himself. In his own version of the metaphor, politically he travels the world selling ideas about how to help the worlds poor selling them mainly to the powerful people and institutions that can turn those ideas into reality. This is at best a partial account, however: in reality the idea that he is most seriously engaged in selling is the one about how those powerful people and institutions are genuinely committed to making the world a more just and equitable place. And hes selling that to us.

Bono is nothing if not cosmopolitan. As an Americanised Irishman who has conspicuously joined forces with the British government in the past and is linked in the public eye with the fate of Africa, Bono is among the most thoroughly transatlantic of elite figures. (Former Irish attorney-general Peter Sutherland, chairman of Goldman Sachs International, ex-chairman of BP, and before that the first head of the World Trade Organization, is perhaps his nearest globe-bestriding equivalent an adviser to banks and governments who has been called the father of globalisation2 and we shall see that Bonos similarities to such a thoroughly establishment character go beyond their moneyed Dublin accents.) In the United States, the belief that Bono brings some vaguely understood European value-set to the global discussion may be part of the reason that he is viewed widely there as a largely benign and politically left-liberal figure. At one of George W. Bushs warmest public appearances with the singer (Bono, I appreciate your heart), the then-president couldnt resist an anecdote that relied for its humour on the perception that Bono was his political opposite: Dick Cheney walked in the Oval Office, he said: Jesse Helms wants us to listen to Bonos ideas. This brought the house down, with Bono himself smiling and clapping.3 This political perception, however, is based upon a misunderstanding of both his own values and those of institutional Europe: neither Bono nor the EU is nearly as committed to social justice and collectivist values as US pundits are wont to insist. Meanwhile, his tendency to verbal and emotional Americanisms is part of the reason he is viewed with greater suspicion in Europe or at least, strikingly, in Britain and Ireland, where Bono is largely a figure of ridicule and the object of often-nasty abuse. The British comic magazine Viz called him the little twat with the big heart, while writer Jane Bussmann suggested in the Guardian that Bono purveys self-serving bollocks, with Africa serving a masturbatory function for him.4 Then there is the oft-heard, surely apocryphal story of a Glasgow U2 gig when Bono silenced the audience and began a slow hand-clap, then whispered weightily: Every time I clap my hands, a child in Africa dies. A voice cried out from the audience: Well, fucking stop doin it then.5

Ridicule of this sort is widespread in Ireland but rare in the Irish media, where U2s friends are many and their influence and patronage large. Indeed, consideration of Bono in his home country is complicated by the peculiarly Irish concept of begrudgery, an alleged national tendency to tear down those who are successful. This tendency, insofar as it exists, is born of a healthy, possibly postcolonial suspicion that the world is less meritocratic than it makes out, or that success has often come at a moral cost. Sadly, begrudgery is more often bemoaned than typified: fuck the begrudgers is Irelands ancient and venerable and ubiquitous version of haters gonna hate.

Petty begrudgery certainly exists; most Dubliners have probably either said or heard the following: I saw Bono in town today, but I pretended not to recognise him I wouldnt give him the satisfaction. In reality, however, Ireland was all too short of begrudgers during the 1990s and 2000s boom years known as the Celtic Tiger, when financiers, bond-holders, politicians, journalists, property developers and even rock stars were inflating a mad bubble that, when it burst, decimated economic life in the country. This book, in any case, has nothing to do with envy and doesnt question the basis for Bonos success the music industry is probably slightly more meritocratic than most but rather how he has chosen to use it politically.

Next page