THE MAKING OF THE ANCIENT GREEK ECONOMY

THE MAKING OF THE ANCIENT GREEK ECONOMY

________________________

INSTITUTIONS, MARKETS, AND GROWTH IN THE CITY-STATES

________________________

ALAIN BRESSON

Translated by Steven Rendall

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2016 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work

should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

PRESS.PRINCETON.EDU

Ouvrage publi avec le concours du Ministre franais charg de la CultureCentre national du Livre.

This book is published with support from the French Ministry for CultureNational Book Center.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Jacket art courtesy of Historic Ornaments and Designs CD-Rom and Book, 2003 by Dover Publications, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bresson, Alain.

[Lconomie de la Grce des cits. English]

The making of the ancient Greek economy : institutions, markets, and growth in the city-states / Alain Bresson ; translated by Steven Rendall. Expanded and updated English edition.

pages cm

Originally published in 2 vols.: Paris : Armand Colin, c2007 and c2008.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-14470-2 (hardback : alkaline paper) ISBN 978-1-4008-5245-1 (e-book) 1. GreeceEconomic conditionsTo 146 B.C. 2. Urban economics. 3. Cities and towns, AncientGreece. I. Rendall, Steven, translator. II. Title.

HC37.B7413 2015

330.938dc23

2015017835

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book was originally published in France, Armand Colin, Publishers

This book has been composed in Adobe Jenson Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

EXPANDED CONTENTS

FIGURES

TABLES

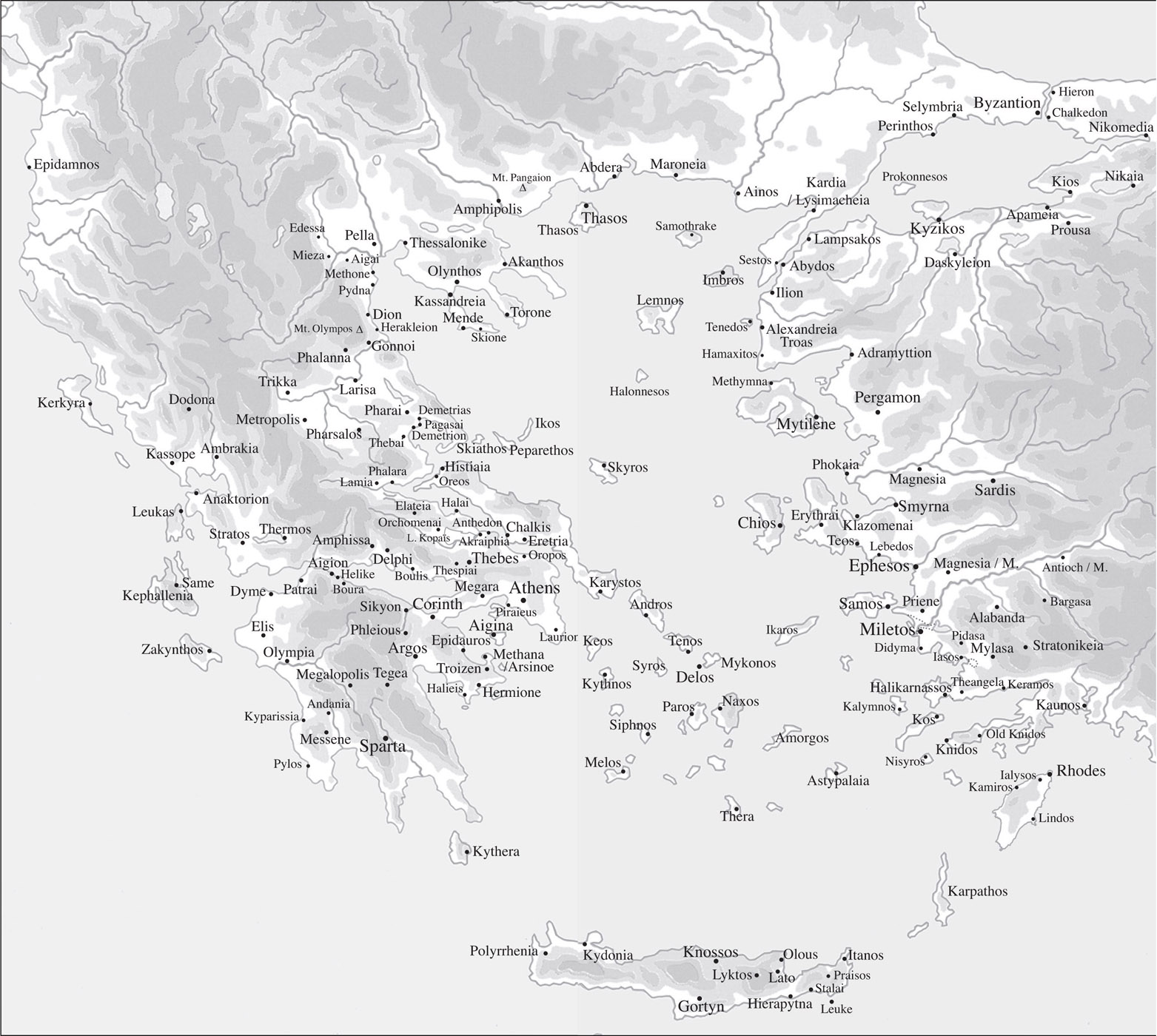

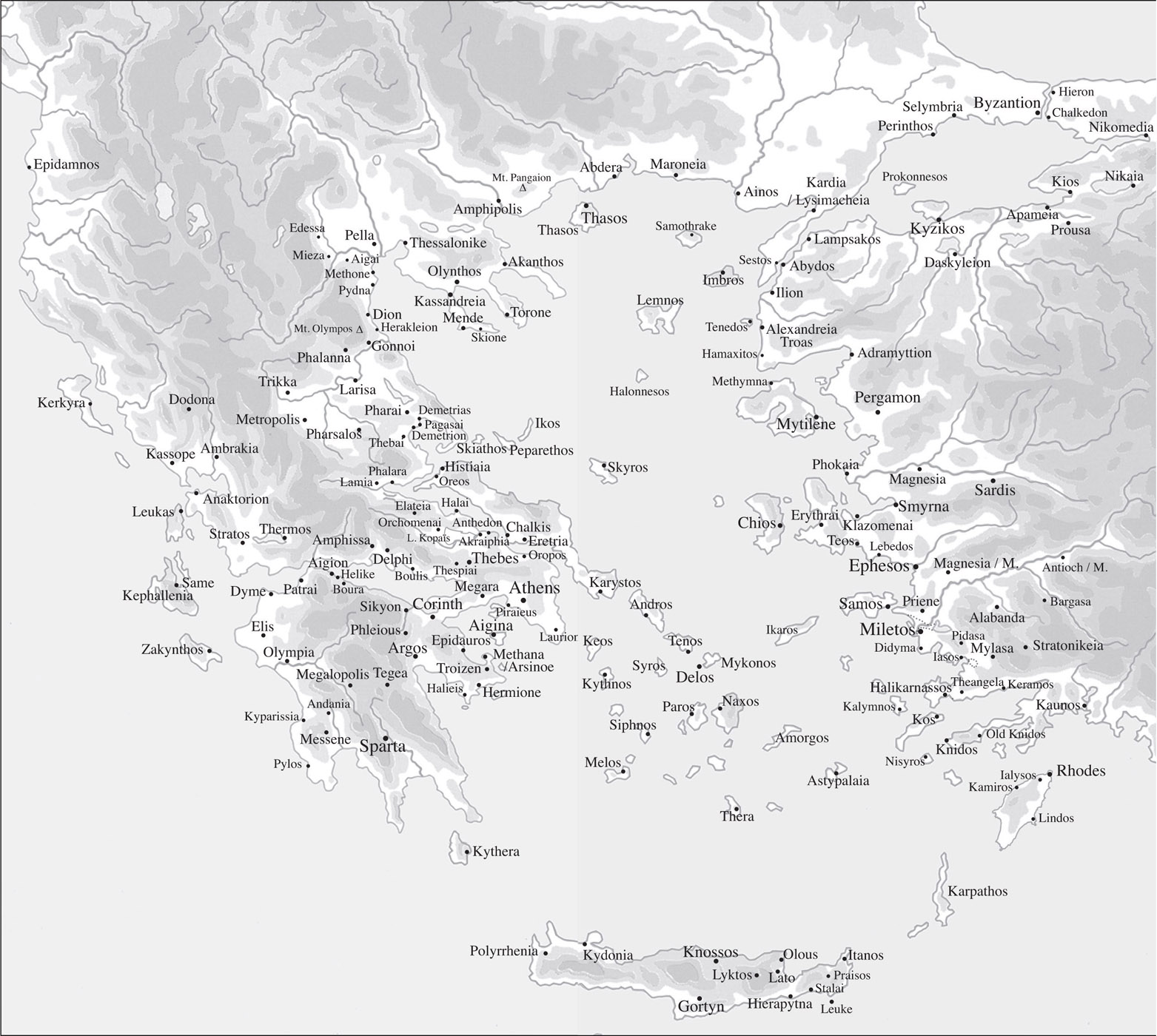

FIGURE 1.1. Map of Greece

______________

INTRODUCTION

______________

This book has a hero: not Achilles or Pericles, but the exceptional economic growth that took place in the ancient Greek world in the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods. But why this focus on growth? Is there any legitimacy in studying growth in a traditional society? And what if the worlds of the past were worlds of no-growthand even showed no interest in growth? Wouldnt this emphasis on growth correspond to a form of obsession characteristic of our modern world, where it is the be-all and end-all of every economic policy? And ultimately, was there any economic growth at all in the ancient Greek world?

The unfortunately still common clich that there was no interest in growth in the ancient world and other societies of the past, and thus that for this reason it would be illegitimate to apply the concept of growth to these periods, is doubly misleading. First, it is not correct to imagine that in the past people were unable to observe phases of prosperity or wealth shrinkage, and that they could not have aimed at increasing their individual or collective riches. Second, and above all, growth is an abstract construct, and thus it stands to reason that before the recent development of economic analysis it was impossible to reason in terms of growth.

But in turn this leads us to an even more fundamental objection, which is that of the legitimacy of applying modern concepts (in this case, economic concepts) to societies of the past. Here again the answer is easy. Growth is an objective process in the sense that it can be independently measured. How many people were there? What was their standard of living? Did the population and the standard of living increase, stagnate, or decline? Were the evolutions of population level and standard of living parallel or did they move in opposite directions? Insofar as growth can be objectively measuredalthough this is an especially difficult task for societies where archives have disappeared and only proxies can be usedit is perfectly legitimate to analyze growth and processes of growth for any society of the past. In any case, the difficulty of measurement cannot be a pretext for refusing to face up to growth as the central issue of economic history.

The focus on growth as the goal of economic-historical analysis is thus central to this book. At the outset, it should be observed that, in economic terms, growth can be positive, negative, or null (which invalidates the argument of the alleged obsession with growth on the part of economists and economic historians). Periods of negative growththat is to say, in more ordinary terms, periods of decline or brutal collapse of the quantity of goods availableare of course also part of the investigation. Therefore, saying that the Greek world enjoyed a period of economic growth in the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods is in fact a shortcut for saying that it had positive economic growth. Above all, thinking in terms of growth also entails thinking in terms of factors of growth: labor, capital, and technology. By adopting this perspective, the economic historian benefits from the wide array of tools, concepts, and hypotheses that have been made available by what is conventionally called economic science, from the works of the founding fathers (Smith, Ricardo, Marx, Keynes) to the most recent research, hypothesesand controversies.

Bringing to light and analyzing the exceptional (positive) growth experienced in the ancient Greek world is the first task of this book. In doing so, it directly contradicts the previous orthodoxy, which, while granting that there was some limited demographic growth, described ancient Greece as a no-growth society. Domestic self-sufficiency, a negligible foreign trade except in luxury goods for the elite, a lack of economic initiative and technological stagnation, and finally an absence of per capita economic growth are supposed to have been the main characteristics of the ancient Greek economy. This book shows quite the opposite: that complete domestic self-sufficiency is a pure myth; that foreign trade was fundamental and concerned not only luxury goods but, at an unprecedented level, basic consumer goods for the mass of the population; that in the long term technological innovation was remarkable and could result in a reallocation of the workforce; that there was per capita growth, at a level unprecedented before the early modern period. This does not (in any way whatsoever) make the ancient Greek economy a modern economy. But cataloguing what it lacked or missed as compared to a modern society would be nonsensical. Instead, we should emphasize that Greece experienced a process of growth that found no parallel in other cultures of that time. Wealthy Hellas, as Josiah Ober has put it, is thus an appropriate definition for Greece in this period.

But measuring growth is only one side of the economic historians task. The other side consists in investigating the institutional developments that made it possible to reach a certain level of labor supply, capital accumulation, and technological knowledge. Rendering the complexity of these evolutions is the key to making sense of the process of growth. This is why, for Greece, this book is also about the ecological milieu and the natural resources that were available, or not available; about demography and the specific demographic and social structures that conditioned the labor supply; about patterns of consumption; and no less about the global political and legal framework than about the specific institutions organizing economic life. Of course, social constructs and antagonisms are also a significant part of the picture. Showing how growth was perfectly possible in a traditional society, as Philip Hoffman has already proved in the case of early modern France, is a fundamental aspect of this research.

Next page