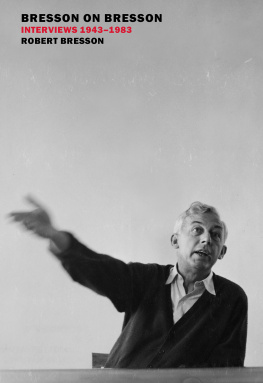

Bresson on Bresson

Interviews 19431983

ROBERT BRESSON

Edited by Mylne Bresson

Translated from the French by Anna Moschovakis

Preface by Pascale Mrigeau

New York Review Books, New York

PART ONE

Public Affairs

Les affaires publiques

1934

PART TWO

Angels of Sin

Les Anges du pch

1943

PART THREE

Les Dames du Bois de Boulogne

1945

PART FOUR

Diary of a Country Priest

Journal dun cur de campagne

1951

PART FIVE

A Man Escaped

Un condamn mort sest chapp

1956

PART SIX

Pickpocket

1959

PART SEVEN

The Trial of Joan of Arc

Procs de Jeanne dArc

1962

PART EIGHT

Adaptation

PART NINE

Au Hasard Balthazar

1966

PART TEN

Mouchette

1967

PART ELEVEN

The Sound Track

PART TWELVE

A Gentle Woman

Une femme douce

1969

PART THIRTEEN

Four Nights of a Dreamer

Quatre nuits dun rveur

1972

PART FOURTEEN

Lancelot of the Lake

Lancelot du Lac

1974

PART FIFTEEN

Notes on the Cinematograph

1975

PART SIXTEEN

The Devil, Probably

Le Diable probablement

1977

PART SEVENTEEN

LArgent

1983

R OBERT B RESSON (19011999) was born in Bromont-Lamothe, France. He attended the Lyce Lakanal in Sceaux, and moved to Paris after graduation, hoping to become a painter. He directed a short comedy, Affaires publiques, in 1934, but his work was curtailed by the outbreak of World War II. He enlisted in the French army in 1939 and was captured in 1940, spending a year in a labor camp as a prisoner of war. After his release he returned to Paris and directed Angels of Sin (1943), his first full-length film, under the German occupation. Les dames du Bois de Boulogne followed in 1945, and in 1951 Diary of a Country Priest was met with widespread acclaim. His next film, A Man Escaped (1956), which follows the memoirs of Andr Devigny, a French Resistance leader incarcerated during World War II, became a hit. He made eleven more films over the next three decades, including Mouchette, Au hasard Balthazar, Pickpocket, Lancelot of the Lake, and LArgent. Throughout his career Bresson eschewed the use of theatrical techniques and employed nonprofessional actors whom he referred to as models. Raised in the Catholic faith, he worked on and off throughout his career on an adaptation of the book of Genesis, which never saw fruition. He died in Droue-sur-Drouette at the age of ninety-eight.

New York Review Books also publishes Bressons celebrated Notes on the Cinematograph.

Preface

To let the camera lead me... where I want to go.

FILMMAKERS HAVE long resisted discussing their work. Robert Bresson is no exception. Not that he hasnt done so at all; like other auteurs deemed to have some commercial value, he has had to succumb to the imperatives of promotion, at times finding in the exercise a surprising sense of pleasure, which permeates these pages. Robert Bresson played the game as well as anyone, but without ever departing from the rules he had established for himself. Editors recall having to drastically reduce their planned page count after Bresson had reread an interview: Once he had pruned, corrected, redacted, and amended it, no more than four of the eight or ten envisioned pages would remain, five on a good day.

Rereading himself, Bresson followed the same practices he had developed for looking at the screenfor that was how he edited his films, more so than in the editing room. He disliked touching film; it was not a fetish object for him. Unlike some of his contemporaries, he said only what he wanted to say; he didnt let his ideas become consumed by the fire of conversation, refused to let his words get lost. In everything, he sought clarity; he loved the mark, and to stress his abhorrence for vapid speech he half-jokingly quoted scripture: Every idle word shall be counted. We can let this idea guide our reading of his words, here assembled by his wife in an order that respects the chronology of his oeuvre and helps us understand that Bresson, though he evolved, changed little. And yet, as he remarked on several occasions, he didnt recognize himself in the image reflected to him by those who loved his films.

Not that he never tried to explain himself, to specify the nature and meaning of his principles and continually, dutifully respond to the same questions asked over and over againmost notably the one about actors. A good craftsman loves the plank he planes, he declared as early as 1943, speaking of his mtier in a way that also evoked, unwittingly, the work he would be obliged to do in the field that had not yet been named Communications. In his eyes, it probably had more to do with transmissionas alluded to elsewhere, in his masterful Notes on the Cinematograph. And it was how he set about stripping the wires, to pick up on a phrase from his 1963 interview with Georges Sadoul. Strip the wires: the only way to get the current to flow.

The current flows; it speeds along and sparks, resulting in electrifying conversations not only for those who admire his films but for those who dream of the day when they might follow in his footsteps. For the latter, Bresson serves as a reminder of the merits of reflecting on the art of cinema before engaging in its practice. Hardly an extravagant recommendation. But: to think about cinema? We all know that he would say cinematography: in his eyes, in his speech, in the words he penned, they were not the same thingif they were, what use would we have for the two distinct terms? So: Lets use cinema to refer to todays films, and cinematography to refer to the cinematographic art: an art with its own language, its own means. (1965)

The distinction originated in the conviction of his analysis: There is an attempt to turn the cinema into a filmed version of the theater, though it has none of the theaters brilliance because theres no physical presence, no flesh and bone. There are only shadows, shadows of the theater (1957). One variation among others, but the idea is the same: Characters dont give life to a film as they do to a play because they arent present in flesh and bone. But a film can give life to its characters. How many years, how many dozens of years will it take for us to recognize that theater and film are incompatible? (1963). Five decades have passed and the confusion still persists, further amplified. We continue to wait, without much hope. Though we do have Robert Bressons filmsjust thirteen of them, made over a career of forty years and followed by a silence of sixteen.