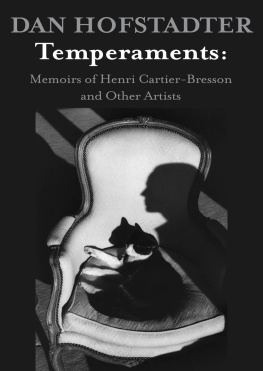

Temperaments

Memoirs of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Other Artists

Dan Hofstadter

Contents

Preface

I was struck recently, in rereading the 1992 edition of this book, by the changes that the intervening years had seemingly wrought in its meaning and its very texture. Like an old house surrounded by new constructions, it had assumed an unexpected appearance, and some of these new aspects I scarcely recognized. For one, I now doubted whether the reader would be wholly convinced that my intentions were descriptive rather than critical; and I also saw, quite suddenly, that though Id had no intention of favoring any particular artist or artists, I had indeed espoused a particular approach to art, and one that really did merit capturing because it stood on the verge of extinction. (I might add that of all the people I wrote about, only two, Leon Kossoff and Dennis Creffield, are with us today.)

It may be useful to bear in mind that the material in that original edition consisted exclusively of profiles commissioned by the New Yorker. (The postscript about Henri Cartier-Bresson and the memory of Mark Rothko to be found here are recent additions.) As such, all were intended as literary portraits, not critical evaluations, although certain truant judgments and an impish tendency to cock an affectionate snook at my subjects do creep into the prose (the latter being, I admit, a typical New Yorker-esque failing of the period). By and large, however, as indicated in the original preface, I was merely keen to explore the sensibilities of the generation of my grandparents and that of my parents, a natural interest for anyone.

Why, then, does it now seem as though I was favoring a special aesthetic attitude? It is simply because that attitude, once common, scarcely exists any longer. It was already starting to disappear by the late 1970s, and though I do not believe that in writing about it I was consciously defending it, I was certainly basking in it to the fullest. I wanted to inhabit, and in fact did for a spell inhabit, a social lagoon in which artists worked alone, at a remove from bourgeois society and with a frankly adversarial relation to it. To be a cultivated person, in those days, was to be an outsider, or, as Robert Motherwell perhaps too hopefully put it, one in whom there was no knowing, only faith. Pictures were created in rough congruence with the emotions that had inspired them, without predetermined conclusions, set ways of solving problems, bombastic sizes, or presentational effects.

The bygone form of artistic ambience I am describing was of course called the avant-garde. It has vanished completely, and vanished with it is the psychological excitement that sophisticated people used to feel on first seeing adventurous pictorial work on display. Some critics have felt that it germinated the seeds of its own destruction, others that its armor was too fragile to withstand the onslaught of the market, still others that it was simply coopted by consumer society. Any or all of these postmortems may be accurate, but I had no desire, in writing this book, to offer an analysis of a doomed way of life. I wanted merely to vivify itto see how some people lived and worked, and to offer what I found to the reader.

Daniel Hofstadter, 2014

Acknowledgments

Many thanks are due to the magazine Art and Antiques for gracious permission to reprint from its pages, in somewhat altered form, H.C.-B. Postscript, and Mark Rothko, Talker; also to the Estate of Henri Cartier-Bresson and the Magnum Agency, for the rights to the photograph Our cat Ulysses and Martines shadow (1989) shown on the cover of this edition.

Breakout

Jean Hlion

Jean Hlion was eighty when I met him, one of the two major living representatives of the classic prewar School of Paris. Like Balthus, who was the other, he had never conformed to fashion; and, perhaps for that reason, he had received inconsistent attention in New York. This, I felt, was a pity, for Hlion had worked in the United States off and on for about five years in the late thirties and early forties, and few French painters had played so important a part in the history of the New York avant-garde. Nonetheless, even his most devoted American admirers had found it hard, down the decades, to keep track of his many successive interests and achievements.

Jean Hlion died in 1988. Because he lived so long yet showed only intermittently in this country, every generation of American viewers had practically to discover him for itself. His style was constantly changing, so every generation had its own Hlion, and his lifework still remains out of focus. As if to complicate matters, his images are often too dense with meaning to be emotionally grasped without a lengthy acquaintance. The masses of derelict objects he painted in the past few decadesthreadbare hats, eviscerated pumpkins, wilting plantsinevitably remind you of flux and decay, and his sketchy figures can often seem, like parvenus at a party, only memorandums for an impossible version of themselves. Yet the difficulty of his pictures lies not primarily in their subject but in their style: Hlion has frequently incorporated into his depictions of things the very qualmsembodied in peculiarities of color or linearoused by the act of depiction. His drift into a mannerism of execution put one artistic crowd off his work in the forties and attracted another in the sixties, yet the question remains whether this sort of mannerism, by now an accepted resource of art, is really at the center of his contribution. The undertow pulls hard, but it is not the surf. Looking today at his best pictures, you may well feel that they retain their interest because of their sheer sensuous beauty: that whatever stratagems lie buried within them are only a residue of something elsesomething as simple as a passion for taking the act of painting in a thoroughly free and personal way.

This passion has led Hlion to paint many kinds of pictures, from severe abstractions to highly realistic interiors. He spoke of them all with equal indulgence, probably because he sensed that he could not foster the strong unless he cared for the weak, but also, I suspect, out of loyalty to his vision of his work as an ensemble. Through the years, this vision remained remarkably fixed, and that is one reason that a comprehensive exhibition is the only good way to see Hlion. Another is that his sensibility was steeped in memories of itself, charged with what a French critic called Proustian unease. Some of his pictures seem, in the oddest way, to depict two different moments at once, while others update or commemorate earlier statements. Notes for projects suddenly become projects; reworkings of forsaken themes change the perception of forty-year-old canvases. Some time ago, Hlion did a big picture of a reversible plow, and, scrutinizing his image of this strange implement, you feel that it might well stand for that quality in his work which invites the backward glance.

In the late sixties, before redevelopment had robbed Montparnasse of its musty, mildly Bohemian allure, Hlion worked in a sort of aerial cottage perched high above the rue Michelet. He showed his pictures not far away, in a gallery in the rue du Dragon, near Saint-Germain-des-Prs. As I daily traversed the same territory, I often found myself walking in the rue du Dragon, heading for a student restaurant or a cheap cinema, and several times I poked into the gallery to have a look at his work. I wasnt alone, for a whole new crop of French painters was discovering Jean Hlion. He was the most famous unknown painter in the worldfamous, that is, among artists and the art-obsessed, unknown for all practical purposes to the general public. Strange to say, he was old even then, with terrible eyesight and a troublesome heart, but to judge by the pictures he still swung his brush with undiminished vigor. I knew that hed made his name as an author of austere geometrical abstractions, but later had turned to representationan unusual and intriguing progression in those days. The broadly brushed canvases in the rue du Dragon revealed a feel for the economics of form, and there was something in his style akin to good muscle tonea readiness of response to whatever was developing on the canvas. He was bold, too: he seemed to take on subjects on a dare. Sometimes hed set his easel up before a window that looked out over the wilderness of chimney flues above the rue Michelet, and in the colors he chose I recognized the light of the neighborhood sky, which in its cool clarity often reminded me of a glass of water. In other images I recognized places and things Id never seen, for many of Hlions pictures had the feverish compulsion of a dream.