Mark Rothko

FROM THE INSIDE OUT

Mark Rothko

FROM THE INSIDE OUT

Christopher Rothko

Copyright 2015 by Christopher Rothko.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Mark Rothko Song

Words and Music by Dar Williams

Copyright 1993 Burning Field Music

All Rights Administered by BMG Rights Management (US) LLC

All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard Corporation

yalebooks.com/art

Designed by Jo Ellen Ackerman

Set in Frutiger Next Pro type by Linotype

Printed in China by Regent Publishing Services Limited

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015937426

ISBN 978-0-300-20472-8

eISBN 978-0-300-21281-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

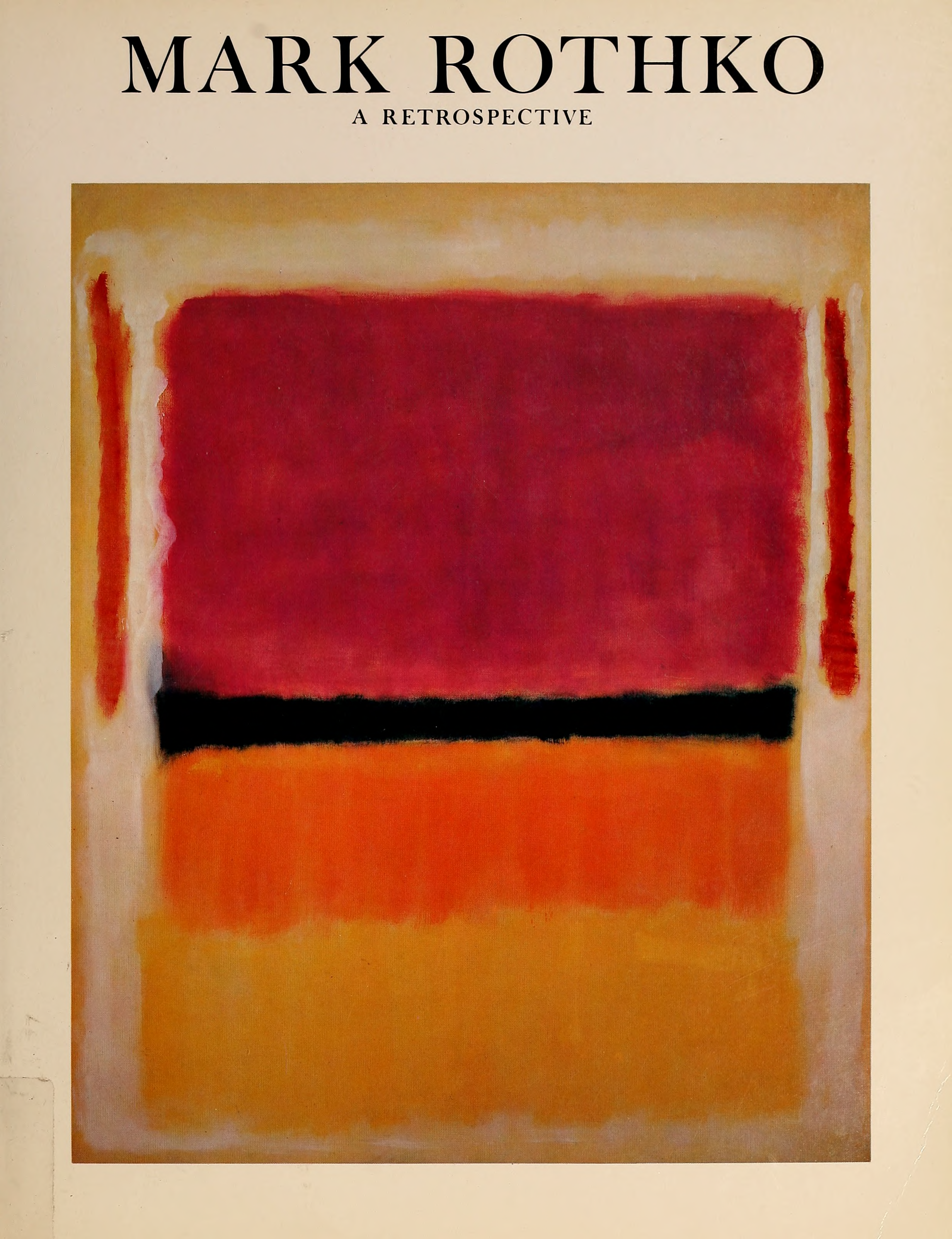

Jacket illustrations: (front) Untitled, 1950s60s; (back) Mark Rothko in his studio, 195253. Photograph by Henry Elkan. Copyright 2015 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko.

Frontispiece: Mark Rothko in his studio, 195253. Photograph by Henry Elkan. Copyright 2015 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko.

For my wife, Lori

my source of perpetual inspiration

Contents

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the people who helped make this book a reality: my sister Kate Rothko Prizel and brother-in-law Ilya Prizel, who have offered wise counsel throughout; Laili Nasr, the definitive source for all things Rothko; Henry Mandell, who brings art even to the mundane; Marion Kahan, who has forgotten more Rothko history than most others will ever know; Farida Zalitelo, a magician who brought Rothko back to Latvia; Alytia Levendosky, Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, and Stephen Fox for their scholarship and friendship; Walter Gadlin, for his opinions literary and otherwise; Sunetra Gupta and Isy Morgensztern for their encouragement; Mary Sutherland, who introduced me to half the publishers she knows; Jonathan Rosen, an occasional sounding board with a sympathetic resonance; and my children, Mischa, Aaron, and Isabel, for just being themselves and allowing me, from time to time, to be a writer.

I would also like to thank my terrific editing and publishing team: Susan Whitlock, who has read more CHR writing than anyone still standing; Amy Canonico, a close second, who somehow always manages to convince me that she is reasonable; Patricia Fidler, who has trusted me for two big projects; Michelle Komie, who got the ball rolling; Heidi Downey and Miranda Ottewell, who have deepened my appreciation for syntax and the semicolon beyond what I thought possible; and Elizabeth Malchione, who helped with all the research that involved typing www rather than opening a book.

Thank you to my crack legal team, Adrienne Fields and Karen Berry.

Finally, thanks to all the helpful image people: Janet Hicks at ARS , who probably never wants to see another Rothko; Sara S. Sanders-Buell at the National Gallery; and Lindsay McGuire at Pace Gallery.

Prologue

Open vistas of the intangible, forbidding because they seem to contain so little. Colors so immediate and yet evocative of the infinite. Deeply saturated surfaces that remain diaphanous and fragile. Since they first drew notice in the late 1940s, Mark Rothkos works have given viewers pause and left them wondering what they have seen, if indeed they have seen anything at all. I make no attempt to demystify these paintings here, nor do I wish to render them familiar, as their otherness is so central to their ability to make us look anew. Rather, by examining many facets of my fathers career, I hope to make his works not easier but more directly approachable. I indicate paths in that might have been less clear before, even as these paths remain very much the viewers to tread. And if Rothkos works still make us uncomfortable, then perhaps it is not comfort we should be seeking.

First and last, this volume is a journey of discovery. I lead the reader along the same course I myself followed to learn more about my fathers work and why it affects us so. Mindful of the full scope of Rothkos output, I highlight the broad brushstrokes but also the fine lines, looking to foster comprehension and bring the reader closer to the paintings. By examining the details of his oeuvre, we can appreciate not only how the works function but also how they reveal some glimpses of the man who made them. For my father is embedded deeply in his work, and breathes a fundamentally human spirit into each of his paintings. That humanity speaks to us and serves as a touchstone in understanding these elusive compositions as well as their often-elusive creator.

What I share here are the understandings I have developed through three decades working with my fathers art. My observations are necessarily personal, but they draw primarily on my active work, carried out in tandem with my sister, Kate, presenting Rothko exhibitions and publicationscoordinating, hanging, lighting, curating, researching, archiving, proofing, editing, lecturing, and writing. During this time my vista has been almost entirely filled with Rothko, and these essays are the fruits of that immersion.

My understandings are abetted by whatever instinctual comprehension of, and affinity for, the work I possess as my fathers son. I have no doubt that these instincts exist, and I refer to them from time to time throughout this volume. Still, their mechanism remains to me mysterious and obscure. I was six years old when I lost my father, so I have no vast cache of private communications to trawl as I think about the art. And certainly the six-year-old is in no position to write a kiss-and-tell, so those seeking copious revelations about my fathers personal life will be disappointed.

Rothko from the inside out is the viewpoint I offer. I do not claim any great knowledge of art history beyond what my own love for art has taught me. Nor do I attempt to codify the many influences on my father, how his artwork relates to that of his contemporaries or to the great procession of forebears whom he revered. Instead I examine the development of his own artwork; how the different periods of his output relate to one another, how his technique evolved, how and what he hoped to communicate, and how the progression of his art interacted with the events of his life.

I am not suggesting that Rothko worked in some hermetically sealed environment or that there is not much to be understood by considering his communications with the world around him. I propose only that a different kind of understanding may be gained by looking at the corpus of his work as a unique and continuous entity with its own internal logic and pathways. By considering the relationship between my fathers different periods, styles, and compositions in different media, we can gain a fuller picture of his aims, beliefs, and the quest for meaning that was at the root of all his work.

My inside-out approach stems from my position as son but also reflects Rothkos own relation to the external world. For although often garrulous and sociable, and close to his family, my father remained, first and last, a solitary man. While very conscious of the art world around himboth its history and the contemporary scenehe tucked that knowledge away as he pondered the expressive task before him. That retreat from the social realm was fundamental to his working process. Specifically, he always painted alone. Always. This was not a manifestation of secrecy but an indication of intimacy with his artwork, driven by the necessity of creating a space for inward focus. Indeed, from his earliest figurative works forward, we encounter very little of the perceivable world in his paintings. Instead we see the realization of his internal viewreality as he experienced it.

Next page