THE ARTISTS REALITY

THE ARTISTS REALITY PHILOSOPHIES OF ART

MARK ROTHKO

EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY CHRISTOPHER ROTHKO

YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW HAVEN AND LONDON

Writings by Mark Rothko

2004 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

Paintings by Mark Rothko

1998 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

Paintings and drawings on paper by Mark Rothko

2004 Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko

Introduction 2004 Christopher Rothko

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in full or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without express written permission from the Estate of Mark Rothko.

Designed by Daphne Geismar

Set in Minion and Syntax type by Amy Storm

Printed and bound in the USA by Thomson Shore

Color insert by Thames Printing Company, Inc.

Jacket illustrations: (front) Manila folder with Mark

Rothkos handwritten notation Artists Reality; (back) Mark Rothko in his studio, 194546

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Rothko, Mark, 19031970.

The artists reality: philosophies of art/Mark Rothko; edited and with an introduction by Christopher Rothko.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-300-10253-4 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Rothko, Mark, 19031970Written works. 2. Rothko,

Mark, 19031970Philosophy. 3. PaintingPhilosophy.

I. Rothko, Christopher. II. Title.

ND237.R725A35 2004

759.13dc22

2004011574

ISBN 978-0-300-11585-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library.

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

10 9 8 7 6 5

FOR KATE, WITHOUT WHOM THERE WOULD HAVE BEEN NOTHING

CR

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the following people for their help and support: Marion Kahan for the ultimate discovery; Janet Saines for her excellent advice; Melissa Locker, Lauren Fardig, and Amy Lucas for their research; and Ilya Prizel and William and Sally Scharf for their many years of wisdom and care.

I also wish to thank the staff at Yale University Press, particularly Patricia Fidler for her enthusiasm and vision, Michelle Komie for her guidance and tireless transcription, Jeffrey Schier for his sensitive editing, John Long for his handling of the photographs, Mary Mayer for her production work, Daphne Geismar for her great modernist design, and Julia Derish, an exceptional sleuth for elusive facts.

I thank especially my wife, Lori Cohen, and children, Mischa, Aaron, and Isabel, for their continual inspiration.

Christopher Rothko

Introduction

CHRISTOPHER ROTHKO

THE BOOK. It was something of a legend to me, resting just on the periphery of my consciousness. It had a weightiness and grandeur that probably exceeded its contents and that were fueled no doubt by its very insubstantiality. There is nothing like mystery to swell the dimensions of the unknown or the dimly glimpsed, and in the murky and turbulent waters left in my fathers wake there was indeed little that was certain to grasp.

Legends, of course, are often based on fact, but since I had never seen the book I could not know where story ended and truth began. Some of the books aura no doubt came from my father, although little of it directly. It may have been filtered through my mother, who came on the scene not long after my father had ceased wrestling with the book. They spoke of it, but certainly not often, to friends and colleagues, but never to my sister or me. The sense of mystery surrounding the book was greatly reinforced during the battle for my fathers papers that quickly followed his death in 1970. In those circumstances, the importance of this still unseen manuscript swelled to Herculean proportions.

This was part of the legacy my sister and I were left in the aftermath of our parents sudden and unexpected deaths. It took nearly two decades to add voice to the whispers that first told us of the book. And it has taken fully thirty-four years to unwrap and then explore the full extent of the manuscript. Now that it is an edited and cleanly typeset document, a published entity, one can easily lose sight of its former state. But for most of my life, cobwebs were more visible than underlying substance.

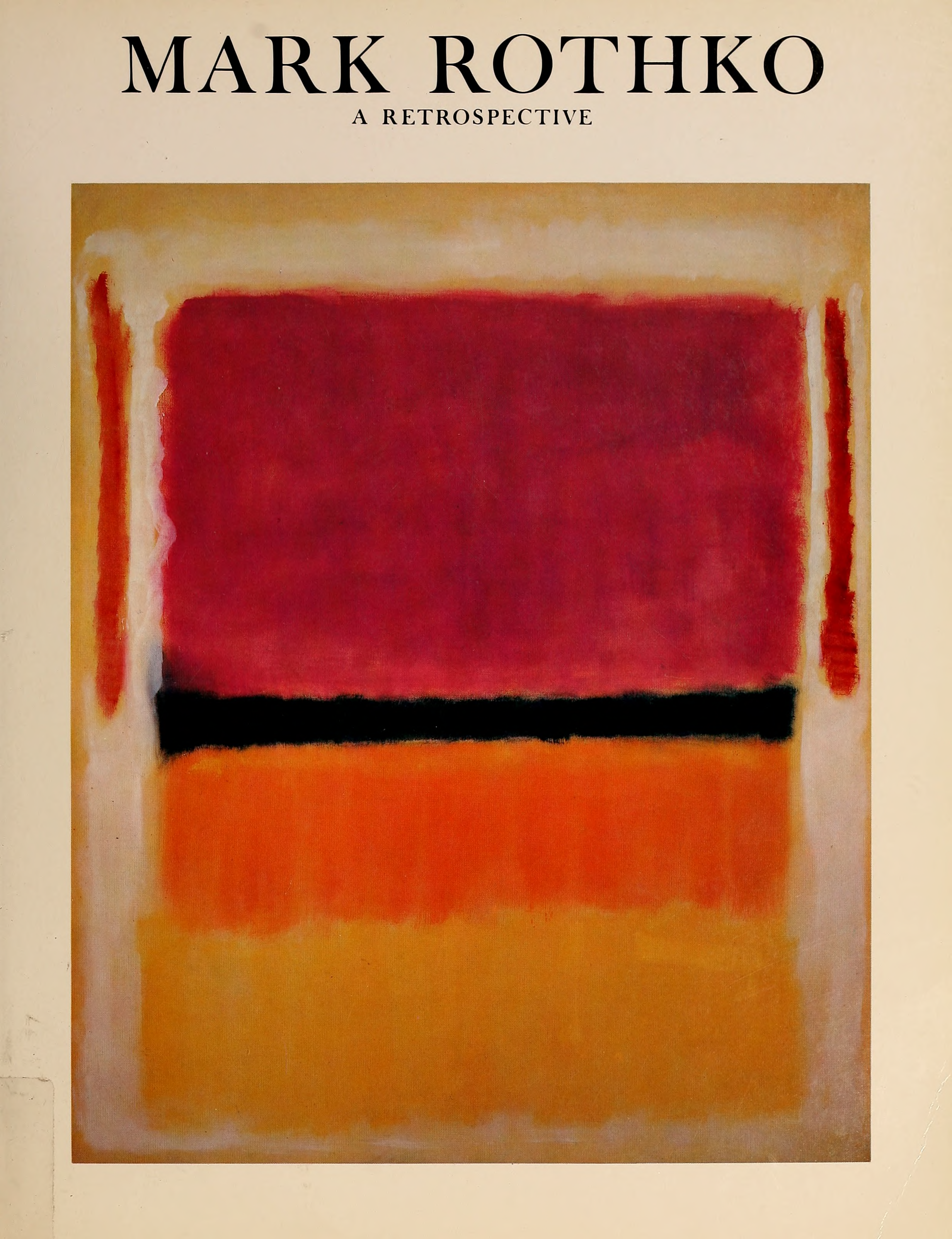

All of this history of shadow and rumor has a certain irony in the context of my fathers artwork. His best-known paintings are large and vibrant and decidedly iconic. They command attention in an immediate and physical way that this small stack of crumbling, haphazardly typed sheets could not hope to duplicate. His work communicates on a level that is explicitly preverbal. Indeed, it would be hard to find less-narrative painting. Like music, my fathers artwork seeks to express the inexpressiblewe are far removed from the realm of words. From their lack of identifiable figures or space to their lack of titles, my fathers paintings make clear that reference to things outside the painting itself is superfluous. The written word would only disrupt the experience of these paintings; it cannot enter their universe.

And yet these writings compel and fascinate us in a way that my father surely would have wanted. Far from discarding this book he never finished and that he wrote before his still unborn, boldly abstract style had brought him fame, my father guarded it and, consciously or unconsciously, stoked the fires of interest in all those who heard murmurs of its existence. His words might be outside his artwork, but they communicate philosophies he still held dear even after paint became his sole vehicle for expression.

One reason this book holds such fascination is that Rothko was explicitly a painter of ideas. He said so himself, over and over, and one can feel them percolating beneath the surface of his otherwise somewhat amorphous abstractions. Indeed, one can ask, if ideas do not exist here, what else is there? But just what might those ideas be? The paintings themselves hold only the most general clues, and no small number of viewers have found themselves sensually stimulated but deeply frustrated by the works very abstractness. With little concrete to grasp, many have walked away from the worksmoved or angeredassuming that, in fact, they must be voids.

So to have in hand a book by Rothkoand not just a book, but one that sets forth his philosophy of artis truly a gift for those captivated by his work. It is like being given the keys to a mystical city that one has been able to admire only from afar.

Or is it?

As with all things regarding my father, the truth is more elusive, even dialectic. First of all, not once in The Artists Reality does he discuss his own work directly. In fact, he never even alludes to it or to the fact that he is an artist. Secondly, the book was written several years before his work became fully abstract, so if he provides clues to the secrets of his floating rectangular forms, they are oblique and, in fact, prescient. In any case, the book does not address what paintings mean, or how to go about finding that meaning. Its essays tell us about what the artist does, what his or her relationship is to ideas, and how he or she goes about expressing those ideas.

These are very concrete reasons why The Artists Reality does not provide a road map to Rothkos work, but they are frankly beside the point. Divining meaning from a painting is not so simple that it can be codified in a book, and Rothko certainly would not have wanted such a guide to his work. So much of understanding his work is personal, and so much of it is made up of the process of getting inside the work. It is like the plastic journey he describes in his Plasticity chapteryou must undertake a sensuous adventure within the world of the painting in order to know it at all. He cannot tell you what his paintings, or anyone elses, are about. You have to experience them. Ultimately, if he could have expressed the truththe essence of these worksin words, he probably would not have bothered to paint them. As his works exemplify, writing and painting involve different kinds of knowing.

Next page