All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2017.

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from The Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA).

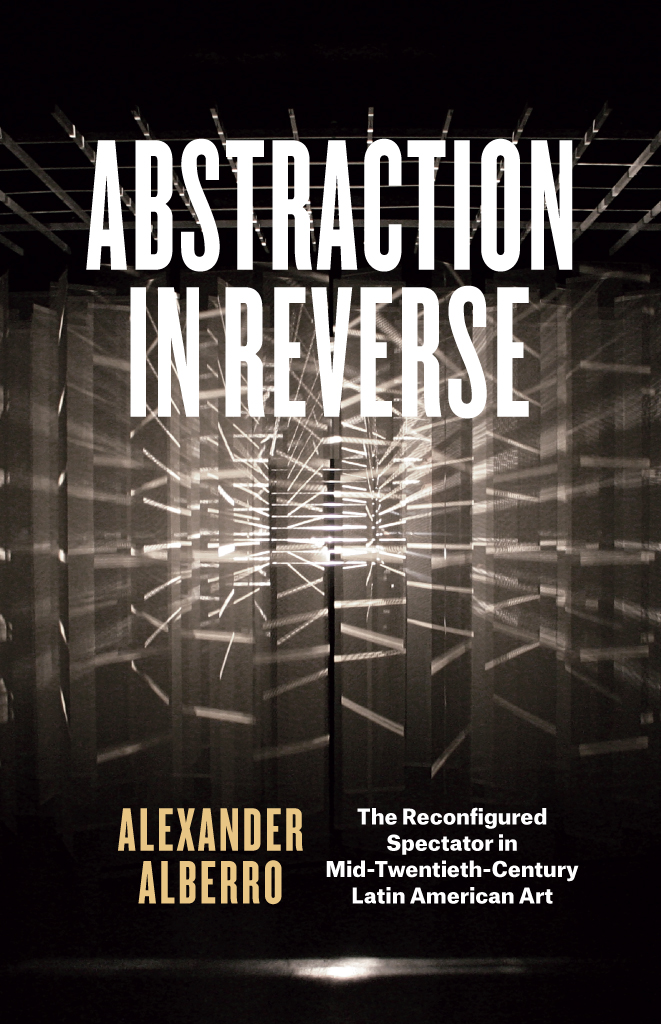

Names: Alberro, Alexander, author.

Title: Abstraction in reverse : the reconfigured spectator in mid-twentieth-century Latin American art / Alexander Alberro.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016030962 | ISBN 9780226393957 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226394008 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Concrete artLatin AmericaHistory20th century. | Concrete artSocial aspectsLatin AmericaHistory20th century. | Arts audiencesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC N6502.57.C6 A43 2017 | DDC 709.04/056dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016030962

The idea to write this book came to me in 2000 when I first discovered the enormous Latin American and Caribbean Collection in Smathers Library of the University of Florida in Gainesville. In this vast archive I came across pristine copies of many of the books, journals, newspapers, and leaflets that have become the cornerstones of this study. I want to begin by thanking that instution, as well as the following archives and estates that permitted me to study their material: Atelier Le Parc (Cachan), Atelier Soto (Paris), Atelier Cruz-Diez (Paris), Carlos Ral Villanueva Archives (Caracas), Cecilia de Torres Archive (New York), Fundacin Cisneros (New York), Fundacin Espigas (Buenos Aires), Joaqun Torres-Garca Archive (Montevideo), Max Bill Archives (Zurich), Projeto Hlio Oiticica (Rio de Janeiro), Institute for Studies in Latin American Art (New York), Instituto Moreira Salles (Rio de Janeiro and So Paulo), Lygia Clark Art Center (Rio de Janeiro), and Raul Naon Archive (Buenos Aires). For granting me interviews and otherwise corresponding, I thank Carlos Cruz-Diez, Analivia Cordeiro, Ferreira Gullar, Roberto Jacoby, Julio Le Parc, Toms Maldonado, Vera Molnar, Francois Morellet, Cesar Oiticica, and Denise Ren.

Along the way I incurred debts of various kinds, large and small, to many people who have invited me to discuss my research on the work of Latin American artists, posed challenging questions, sharpened my reasoning, and just kept the conversation going: Dawn Ades, Mnica Amor, Ricardo Basbaum, Carlos Basualdo, Karen Benezra, Barry Bergdoll, Sabeth Buchmann, Daniel Buren, Kaira Cabaas, Claudia Calirman, Luis Camnitzer, Ron Clark, Diedrich Diedrichsen, Edward Dimendberg, Helmut Draxler, Pedro Erber, Heloisa Espada, Jose Falconi, Hal Foster, Mara Amalia Garca, Lydia Goehr, Robin Greeley, Hans Haacke, Mauro Herlitzka, Max Jorge Hinderer Cruz, Ariel Jimnez, Kellie Jones, David Joselit, Ileen Kohn, Rosalind Krauss, Michael Leja, Arto Lindsay, Ana Longoni, Marta Minujin, Keith Moxey, Graciela Montaldo, Luis Prez-Oramas, Isabel Plante, Jean-Marc Poinsot, Rachel Price, Gerald Prince, Daniel Quiles, John Rajchman, Gabriela Rangel, Elisabeth Sher, Irene Small, Nancy Troy, and Sergio Vega. Gabriel Prez-Barreiro, Andrea Giunta, Nicolas Guagnini, and Adele Nelson improved drafts of sections of the manuscript and generously shared their vast knowledge of this subject, and Caroline Constant, Rosalyn Deutsche, Caroline Jones, James Meyer, and Terence Smith offered critical responses and invaluable advice on the argumentation, prose structure, and overall organization of the book.

The lively debates that took place at the series of colloquiums I organized at Columbia University between 2010 and 2016 with the magnanimous support of Ariel Aisiks and the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA) generated provocative discussions that greatly contributed to the material in this book. A grant from ISLAA, as well as funds from the Virginia Bloedel Wright research endowment at Barnard College, also helped to offset the cost of securing image rights. Let me also acknowledge the many scholarly audiences in venues as different as the Comit International dHistoire de lArt (Montreal), Cornell University (Ithaca), the Courtauld Institute of Art (London), the Fundacin Proa (Buenos Aires), Harvard University (Cambridge), the Instituto Moreira Salles (Rio de Janeiro), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Los Angeles), MACBA: Museu dArt Contemporani de Barcelona (Barcelona), the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofa (Madrid), Princeton University (Princeton), Stanford University (Palo Alto), the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia), and the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), who shifted the direction of some of my arguments in unexpected ways. I also owe a debt to the terrific editorial staff at the University of Chicago Press, Ruth Goring, James Toftness, and in particular Susan Bielstein, who was never reticent about offering criticisms, advice, and editorial suggestions. Rose Rittenhouse handled promotions deftly.

I am also grateful to my unfailing research assistant at Columbia University, Nicholas Morgan, whose efficiency was vital at crucial moments, and to the brilliant students in my seminars at Barnard College, Columbia University, and the Whitney Independent Study Program, from whom I have learned a great deal.

Most of all, my love and appreciation to Ana Lizn, whose Bogot childhood is on every page of this book; to Nora Alter, my best friend; and to Arielle and Zo, who kept things real by rolling their eyes every time their father talked about abstractions and reversals.

Spectatorship after Abstract Art

During the mid-twentieth century, Latin American artists working in several different cities altered the nature of modern art in ways that have never been fully appreciated. In this critical transformation, arts relation to its public was reimagined, and the spectator was granted a more significant role than ever before in the realization of the artwork. These developments unfolded in the context of a complicated mediation of the particular form of abstract art that European modernist artists Theo van Doesburg, Max Bill, and others referred to as Concrete art. This type of abstraction resonated in Latin America not only as a result of European modernisms hegemony but also because it articulated an experience of modernity that, despite all cultural differentiation, was becoming increasingly global. Initially, in the 1940s, Latin American artists with modernist ambitions faithfully adopted Concretism, following their European predecessors in banishing all categories of description and imitation in favor of an emphasis on the sheer inventiveness of a simple operation generated entirely from the mind of the artist and communicated lucidly to the spectator. The task of the spectator in turn was to avoid any particularities that might obstruct her deindividualized gaze and to subordinate herself entirely and without interference to the logic of the art object, enabling the artworks import, its meaning, to be comprehended fully. Vision was the primary means for this model of spectatorship, and any phenomenological aspect of the experience was to be avoided.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).