SAVING ABSTRACTION

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 9780190948573

eISBN 9780190948597

To Bryan

Contents

This book owes its existence to the skill, kindness, and good humor of editors, librarians, archivists, institutions, and friends. First, I thank Suzanne Ryan. She immediately and enthusiastically understood what I wanted to do in this book and her keen insight has made it better. Victoria Dixon has been a lifeline through the publication process and Im especially grateful for her help in the contract and production stages. The three reviewers deeply and generously read the manuscript and offered trenchant criticisms that clarified the stakes of my argument. They each have my thanks.

I began research on Morton Feldman at the Paul Sacher Stiftung in Basel, Switzerland in 2006. For the last thirteen years it has been my scholarly home away from home. There, Sabine Hnggi-Stampfli was my cheerful and masterful guide through the Feldman collection. Her colleagues Tina KilvioTscher, Carlos Chafn, and Johanna Blask made research enjoyable and efficient. Isolde Degen welcomed me each day with a kindness that eased any homesickness I might be feeling. Felix Meyer, the director of the Sacher Stiftung, has been insightful, encouraging, and always generous. Ingrid and Martin Metzger are my Basel family. They provided me with more than just a cozy room, they built up a terrific community around Adlerstrae 31. Many of the ideas found in this book were worked out in conversations at the Sacher, Invino, or in the Metzgers kitchen. Thanks to the dear people that graciously listened: David Beard, Maureen Carr, David Cline, Laura Emmery, Sumanth Gopinath, Roddy Hawkins, John Kapusta, Benjamin Levy, Kate Meehan, Simon Obert, Thomas Peattie, Keith Potter, Ian Quinn, Peter Schmelz, Anne Shreffler, Amy Wlodarski, and Michele Ziegler.

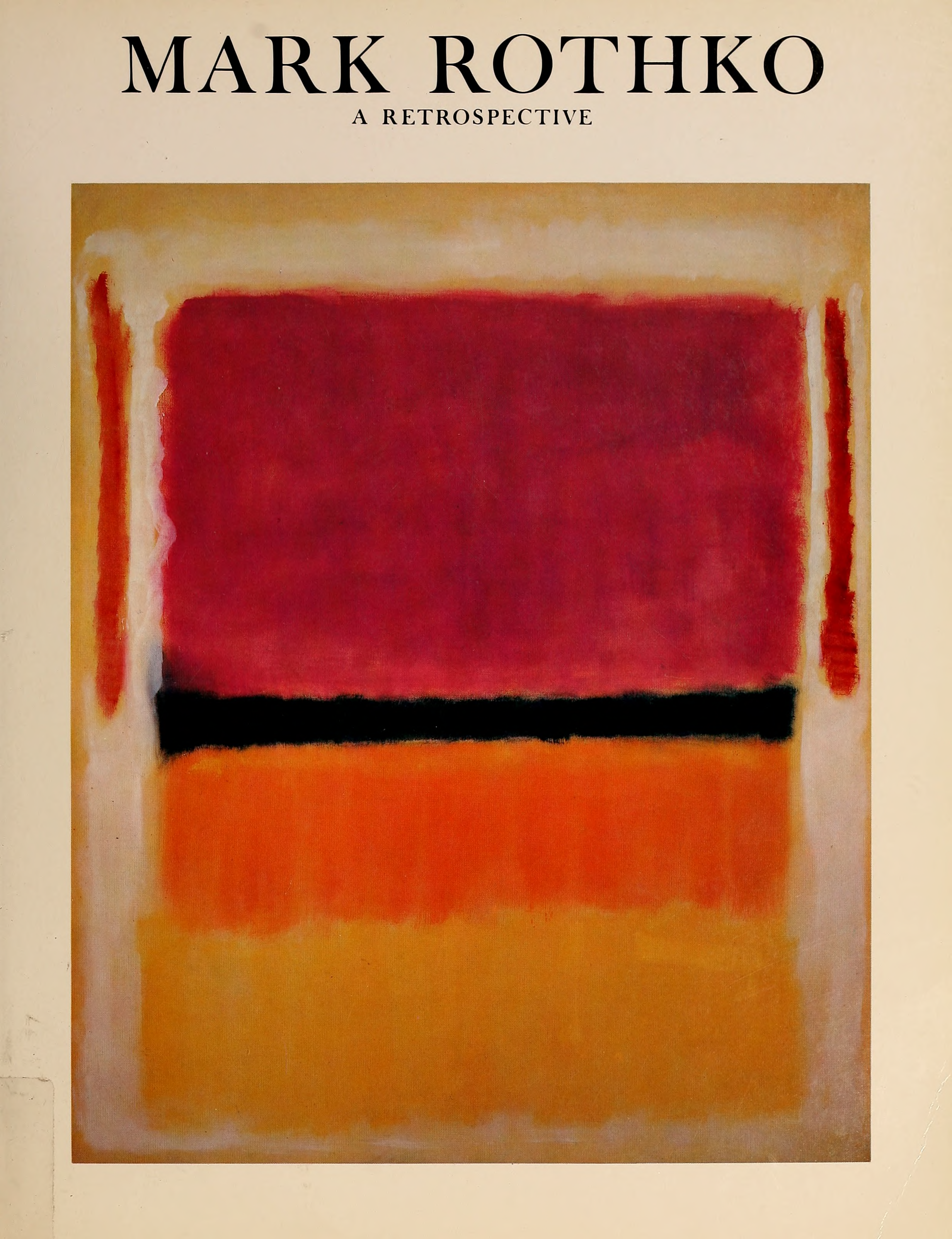

My research into the history of the Rothko Chapel and John and Dominique de Menil was made possible by Suna Umari, former archivist at the Rothko Chapel, and Geraldine (Geri) Aramanda, retired archivist at the Menil Collection. Suna scoured and turned up a treasure trove. Geri added to those riches and guided me through the bounty of the Menil Collection Archive. She helped me see the depth of Feldmans involvement in the de Menilss projects and showed me the scope this book could take on. Since Geris retirement, Lisa Barkley and Lilly Carrel fielded questions that came up along the way and graciously provided me with new archival documents as my writing took its twists and turns. Both were a invaluable guides through the permissions and copyright process, as were Ashley Clemmer, Caitlin Ferrell, William Middleton, and Kristina Van Dyke.

The librarians at Northwestern have been and remain godsends: D. J. Hoek, Gregory MacAyal, Scott Krafft, Sigrid Perry, Alan Ackers, Nicholas Munagian, and Jason Nardis each have my thanks for helping me with my research needs and their kindness.

Other archives and librarians provided essential help. John Bewley at the University of Buffalo allowed me to hear a recording of the premiere of The Viola in My Life 4. Amanda Focke at the Woodsen Research Center in Fondren Library at Rice University kindly digitized materials from the Contemporary Arts Museum collection. Michelle Sawyer at the archives for the Congregation of St. Basil in Toronto dug up what has become my favorite archival objecta letter of Dominique de Menil recounting her visit to Rothkos studio in 1958.

Thanks also to the organizations who contributed to this work financially. Trips to Basel were made possible by a stipendium from the Paul Sacher Stiftung, a Franklin Grant from the American Philosophical Society, and a Faculty Research Grant from the Graduate School at Northwestern University. A fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies gave me a year of leave for research and writing. My dean, Toni-Marie Montgomery, and Associate Dean Ren Machado substantially defrayed production and permission costs.

I benefited greatly from conversations with audiences at Stanford University, Loyola University, the University of Kansas, the University of Pittsburgh, the University of Chicago, Northwestern Universitys Comparative Modernisms Seminar, and meetings of the American Musicological Society and Society for American Music.

Saving Abstraction is to a great extent a product of my institution. The Bienen School of Music at Northwestern University has proven to be an ideal home for a musicologist working on contemporary music. Dean Montgomery eased my transition from the University of Kansas to Northwestern and has been a constant source of warm support and sober guidance. Hans Thomalla, director of the Institute for New Music, has been an ideal collaborator. Donald Nally, director of the Bienen Contemporary/Early Ensemble conducted an exquisite performance of Rothko .

Work on this book was sustained by the energy I draw from my incomparable colleagues and friends here at Northwestern both in Bienen and the University more broadly. Ive been warmly welcomed into the Program in Critical Theory and its core faculty have been dream colleagues. Peter Fenves helped me think through Feldmans investment in Kierkegaard. Penelope Deutscher encouraged me to rework the chapter structure and has been a dependable source of pragmatic professional advice. Anna Parkinson, through conversations and her inspiring writing, helped me clarify my conceptions of emotion and affect. Fumi Okijis friendship supported me through the final stages of writing.

My colleagues in the Department of Religious Studies have had an immense impact on this work. Im grateful for conversations with Robert Orsi and Ive tried to heed his call to take religious experience seriously as both history and presence. He thoughtfully read a draft of and gave me the best complement possible: This is a very weird Catholicism! The book would not have been what it is without J. Michelle Molina. Her careful attention to religious feeling and phenomenology made me see what was possible in my sources. She also introduced me to the scholarship of Brenna Moore, which initiated a sea change in my thought. Michelle gave me the permissions I needed to follow where my evidence led (well beyond musicology proper) and helped me hone the tools with which to interpret them.