To my parents

With the exception of a few minor characters whose personal details and names I have changed to protect their privacy, I have not altered any names or information concerning the people involved.

Copyright 2014 by Gabrielle Selz

All rights reserved

First Edition

Since this page cannot legibly accommodate all the copyright notices, Authors Notes on Sources and Permissions constitutes an extension of the copyright page.

A portion of the prologue and chapter 19 originally appeared in More magazine in 2012.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Devon Zahn

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Selz, Gabrielle.

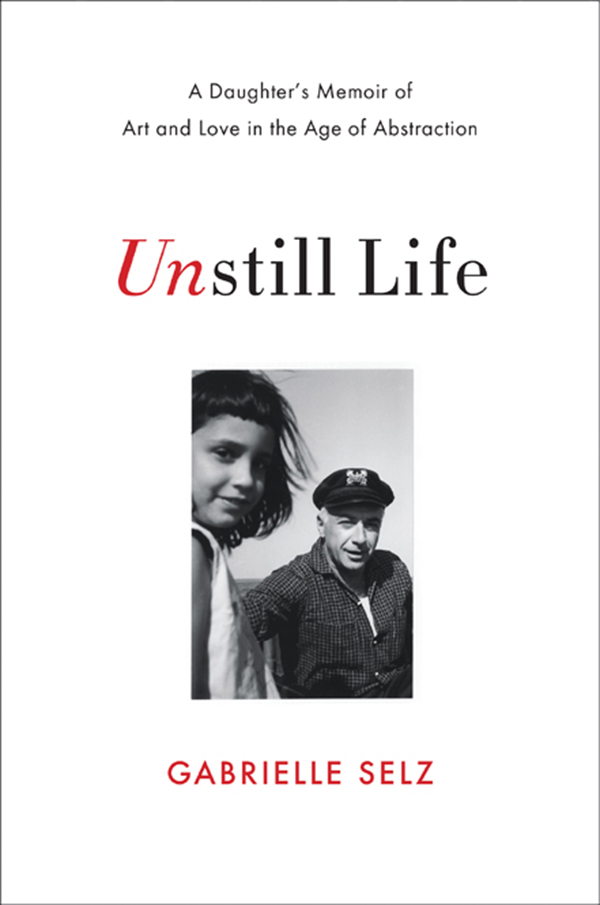

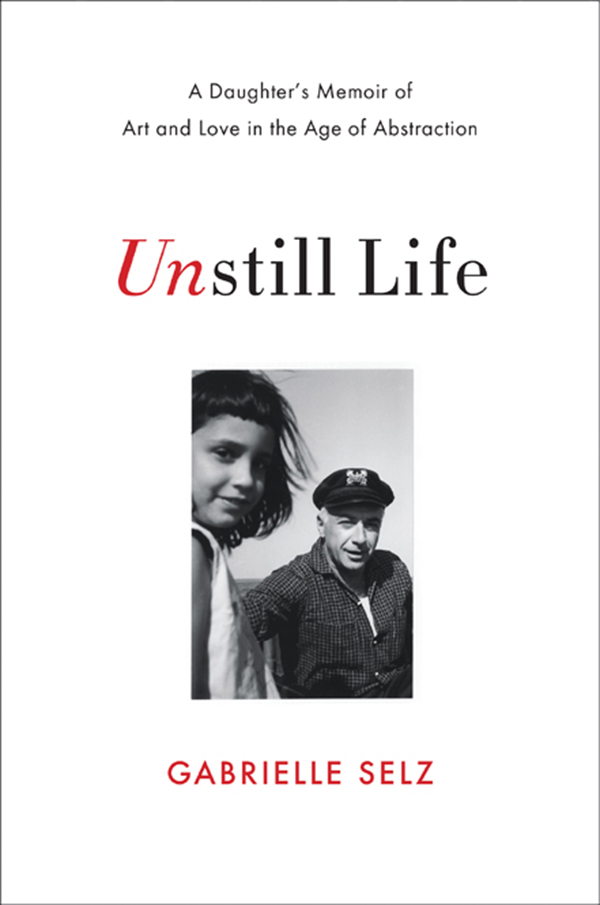

Unstill life : a daughter's memoir of art and love in the age of abstraction/Gabrielle Selz.First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-393-23917-1 (hardcover)

1. Selz, Peter, 1919 2. Art historiansUnited StatesBiography. 3. Art criticsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Art museum curatorsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

N7483.S383S45 2014

708.0092dc23

[B]2013041177

ISBN 978-0-393-24433-5 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Un still Life

To paint a small picture is to place yourself outside your experience... However you paint the larger picture, you are in it. It isnt something you command.

Mark Rothko (I Paint Very Large Pictures1941)

The goal of art is the vital expression of self.

Alfred Stieglitz

By the time my fathers train pulled into the old brick station in Hartford, Connecticut, it was nearly ten, as black as Hades outside, my mother would have said. The platform was deserted save for me and a woman so deeply bundled in a long down coat she looked like a mummy. Still, when my eighty-six-year-old father descended from the passenger car, he waved and called out, Hello! like royalty on parade. His overcoat was buttoned up to his chin against the chill night air, a bright yellow scarf encircled his neck, a red beret sat at a jaunty angle on his head and tufts of white hair poked out above either ear.

Arrivals are his most perfect incarnation, I thought as I watched him swing his small shoulder bag carelessly. But instead of coming toward me, my father immediately made a beeline for the woman hidden in her big coat. In his excitement and fatigue, hed mistaken the down-coated figure on the platform for my mother.

Dad, I called out as the woman backed away. Hearing my voice, my startled father turned toward me with such a look of confusion that I burst into tears.

Oh, he said, catching me in his arms. Tell your old man all about it.

It was the early spring of 2005, and my mother had just been diagnosed with midstage Alzheimers. When Id called my father with the news a week ago, to my surprise hed volunteered to make the journey east to help me inventory her art collection. My father, the art critic and historian, the intellectual bon vivant, the infamous womanizer, had come to help me appraise and catalogue, to rally and reflect and bid his final goodbye to the woman who had remained the love of his life.

My mother was my fathers first wife. They were married for seventeen years. During the 1950s and 60s they were central figures in the New York art world, when my father reigned as the chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art and the New York Times dubbed him Mr. Modern Art. Our home hosted the most celebrated artists of the day: charismatic Willem de Kooning, who invented Abstract Expressionism and then changed direction to merge gestural painting with human depiction and reinvent the face; somber-faced, bespectacled Mark Rothko, who painted great tablets of color and wanted his paintings to evoke the depth of emotion usually only felt through music and poetry; swarthy Franz Kline, with his thick black mustache, who was labeled one of the original action painters; Robert Motherwell, who painted iconic, geometric forms and was accompanied by his elegant wife, Helen Frankenthaler, whose paintings of thinned-down colors washed across the unprimed canvas; Ad Reinhardt, with a square head and broad shoulders, whom we called the black monk because of his dark monochromatic paintings; Philip Guston, a man with a huge slab of a face, a cigarette always dangling from his lips, who painted in soft pinks; and wild young Larry Rivers, who combined elements of Expressionism with early Pop art. Standing at the edge of the dining room of our Central Park West apartment, this was the world I watched: bright, saturated with art, glamorous but intimate, risqu and intellectual. At its center was my insatiable, animated father.

My elusive mother was his perfect contrast. She was a writer who liked stories more than peoplewith the exception of my father, whom she adored more than anything. She liked to sit still while floating free. He liked to dart about and do. He was as full of turmoil as the art he championed. She was as contained and mysterious as a box by Joseph Cornell, her favorite artist. For a time he enlarged her world and she anchored his. Together they were two riddles that solved each other.

Then, abruptly in 1965, after seventeen years of marriage, the perfect design of their point-counterpoint fell apart. When I was seven, my father quit the Museum of Modern Art, abandoned my mother and our family and moved to California to direct his own museum. In less than ten years, he remarried four more times. My mother said wryly, Your father has a gift for starting over. Though my mother had her share of boyfriends, she never remarried. She clung to the hope that theyd end up back together. Between each of his marriagesand often during themmy parents would briefly reunite. But the same problem recurred. My father was chronically, flagrantly unfaithful.

Still, artfar more so than their childrenremained their passion and their glue.

THE MORNING AFTER my fathers arrival, I found him wandering through my mothers house ogling the art. Stopping in front of the dining room table, he patted it like an old friend. He caressed the smooth surface of the elegant Biedermeier cabinet in the corner. Hands clasped behind his back, he smiled and nodded at the paintings on her walls, more than friends, some actually beloveds. Over against the couch he picked up a small Renaissance drawing of the madonna and child that Id set aside. I gave this to your mother when she was pregnant, he said excitedly. Dont sell it, give it to me. Oh, wouldnt it be nice to have it again?

I put my coffee cup down and pried the madonna from his grasp, remembering how my father had a special knack for getting what he wanted. Mom told me to keep the Carracci. Its a mother and child. Besides, you took what you wanted when you left. What would you do with it now?

Shes so beautiful. My father eyed the madonna with yearning, as if she were a fair damsel escaping his advances.

But I marched away, clutching the picture. I was going to put this beautiful lady high up on a shelf and out of his reach.

Next page