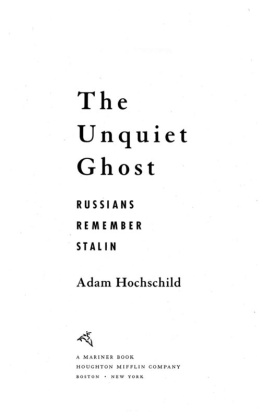

First Mariner Books edition 2005

Copyright 1986 by Adam Hochschild

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Hochschild, Adam.

Half the way home : a memoir of father and son / Adam

Hochschild.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Viking, 1986.

ISBN 0-618-43920-X (pbk.)

1. JournalismUnited StatesBiography. 2. Hochschild, Harold K., 18921981. 3. BusinessmenUnited StatesBiography. 4. Fathers and sons. I. Title.

PN4874.H58A3 1996

070'.92'273dc20 [B] 96-31982

e ISBN 978-0-547-56156-1

v2.1017

Portions of this book appeared, in different form, in Mother Jones

magazine.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Syracuse University Press,

publishers of the 1996 edition of the work, who graciously assisted

with the Mariner Books reprint edition.

for Arlie

I

THE MOST VIVID MEMORIES I have of my childhood are of the summer evenings when Boriss plane took off.

Boris Vasilievich Sergievsky, captain in the Imperial Russian air force, World War I fighter pilot, winner of the Order of St. George (which entitles the bearer to a personal audience with the Tsar, any time of day or night), test pilot for the Pan American Clippers of the 1930s, tenor, gourmet, lover, horseman, and adventurer, was, miraculously, my uncle. One day he had flown his plane down from the sky and, to the complete shock of all her relatives, had married my fathers sister, Gertrude. She was then forty-one years old and had almost certainly never even kissed a man before. From that point on, life in our family was never the same.

Gertrude, my father, and their brother all spent the summer with their families on a large estate called Eagle Nest, in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. When I was a boy, in the years right after World War II, Boris was retired from test piloting. He now operated an air charter business in New York City, flying people anywhere they wanted to go in a ten-passenger Grumman Mallard that could put down on land or water. During the summer, Boris spent the week in New York; for the weekend, he flew north to join his family. Then, on Sunday evenings, with a planeload of houseguests also returning to the city, he took off for New York.

First a crew of workmen used Jeep, winches, and a huge set of dollies for the landing gear to maneuver the plane out of its lakeside hangar and onto a concrete apron. Then more people began to arrive: passengers, family members, friends, and spectators, coming by motorboat over the lake, or by horseback or car on the mile-long road that ran through the woods to the hangar.

When his passengers had climbed on board, Boris warmed up the planes engines on shore, watched by a cluster of admiring children. I knelt with my fingers in my ears, a few feet from the right wing tip. Through the cockpit window I could see the intent faces of Boris and his copilot. Their eyes checked instruments on the panel; their lips moved in a mysterious technical jargon I could not hear; their hands reached up. to adjust a wondrous galaxy of switches and levers. First one motor, then the other, gave out a long, shattering roar so loud you felt as if you were standing inside the noise. The aircraft rocked and strained at its wheels; the saplings at the edge of the forest behind it bent toward the ground. Finally the engines quieted to a powerful whoosh, Boris released the brakes, and the plane rolled down the ramp into the water.

Boris taxied out to the middle of the lake, the propellers blowing a wet wind back over us on shore. Suddenly a great white tail of spray spread out behind the plane. Its wheels now folded into its belly, the Mallard lifted higher and higher in the water, transformed into a shape of sleek grace. A motorboat or two raced alongside, then were quickly left behind. At last, triumphantly, the plane broke free of the water and rose into the dusk. The engines roar echoed off the lake; the very mountains vibrated. A plume of water drops trailed from the fuselage, then faded to a fine mist, then to nothing. On the ground, people quietly began talking again, moving slowly, reluctantly, toward the waiting cars. High in the sky, Boris dipped a wing and turned toward New York.

It would be tempting to linger on Boris, for his is the easy story to tell. Anothers is much harder. Look more closely now at the people mounting the steps into the plane. They turn to wave from the cabin door, then duck their heads and step inside. Here is Boris with his square Russian face and hearty laugh; here is his copilot Elmourza Natirboff, a strapping, dashingly handsome young man with jet-black hair and a warm grin; here are laughing guests in brightly colored sport shirts or sweaters, carrying tennis rackets and golf clubs back to the city. And here, the last in line, politely letting the others go first, the only person wearing a suit and tie, is a stocky, middle-aged man with a shy, tense, embarrassed smile, ill-at-ease as he always is at any occasion when emotion is to be shown, even a simple weekly farewell. This book is the story of him and me, from those summer Sunday evenings when I waved good-bye to him and was secretly relieved to see him go, until I held his hand as he died and then was apart from him at last. He is my father.

My father. I always spoke of him, talked to him, thought of him that way. I never called him Dad or Daddy, only, in an awkward way, unlike any other child I knew, Father. There was always a stiffness in the air between us, as if we were both guests at a party and the host had gone off somewhere before introducing us. We never spoke about our relationship with each other, ever. But sometimes, in those uncomfortable silences, I greatly feared that he might do so, and that he might start by inviting me to call him by a less formal name. As if he were indirectly suggesting this, at times I heard him say to someone else in my hearing, Hows your dad? But he never did ask me, and I never volunteered. And so he remained, until th end, Father.

I was an only child. What few friends I had were usually so awed by being invited to fly to the Adirondacks on Boriss plane or to travel abroad with us that they never said anything critical of Father. To my mother, he was the most wonderful man in the world, a man who could do no wrong. I never heard her find fault with him or disagree with him in any way. And so for many years it was unimaginably hard for me to do so.

Father was, I thought as a child, a man of vast endurance. I was sure my own body could never become so strong. Whenever we were at Eagle Nest he rode horseback through the woods for many miles each day. In the summers he swam across our lake and back every evening, more than half a mile in all. Until he was nearly fifty, once a summer he swam a six-mile course through a chain of lakes. And he boxed. With a punching bag, with an instructor at his club gym in New York, and, from the time I was five or six on, with me.

He always initiated it. Adam, do you want to box?

...O.K., I replied, feeling that constant uneasiness.

How about this afternoon at three oclock? Everything in his life was by appointments, for which Father was always precisely on time.

...O.K. I didnt like the boxing, but I could never think of a plausible reason to say no. And he never learned, never took the hint, from the fact that I never suggested that we box.

At three oclock we put on our gloves. For him boxing was not an art, a game, or a chance to playfully vent aggression. It was instead a chance to exercise his upper body muscles. Everything was broken into prescribed movements; every punch fell into categories on a list in his head. He called them out:

Next page