Contents

Guide

Contents

Australia

HarperCollins Publishers Australia Pty. Ltd.

Level 13, 201 Elizabeth Street

Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia

www.harpercollins.com.au

Canada

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

Bay Adelaide Centre, East Tower

22 Adelaide Street West, 41st Floor

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5H 4E3

www.harpercollins.ca

India

HarperCollins India

A 75, Sector 57

Noida

Uttar Pradesh 201 301

www.harpercollins.co.in

New Zealand

HarperCollins Publishers New Zealand

Unit D1, 63 Apollo Drive

Rosedale 0632

Auckland, New Zealand

www.harpercollins.co.nz

United Kingdom

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF, UK

www.harpercollins.co.uk

United States

HarperCollins Publishers Inc.

195 Broadway

New York, NY 10007

www.harpercollins.com

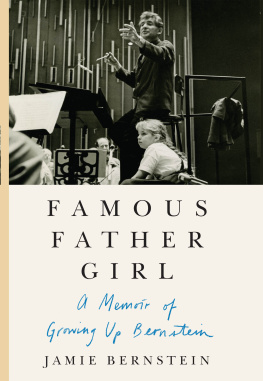

FAMOUS FATHER GIRL . Copyright 2018 by Jamie Bernstein. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

FIRST EDITION

Cover design by Adalis Martinez

Cover photograph by Bob Serating courtesy New York Philharmonic Leon Levy Digital Archives

Where not otherwise indicated, photos are courtesy of the Bernstein family.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to reprint from the following:

ALONG COMES MARY

Words and Music by Tandyn Almer.

Copyright 1965 IRVING MUSIC, INC.

Copyright Renewed.

All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

Reprinted by Permission of Hal Leonard LLC.

Digital Edition JUNE 2018 ISBN: 978-0-06-264137-3

Version 05152018

Print ISBN: 978-0-06-264135-9

To my beloved, delicious family: in every generation.

LB, Jamie, and Henry the dachshund, 1953.

Knickerbocker News, Photo by Bob Paley

T he story goes that when my brother was born, Henry the dachshund and I were both so outraged by the intrusion that we jointly peed on my mothers pillow. Nor was I consoled a year later, as I warily watched Alexander pull himself to his feet; was this little interloper going to walk now, too?

But as soon as Alexander could talk, I realized what the point of a brother was. We became coconspirators, eventually expanding into a trio with our younger sister, Nina. Together we created a force field around ourselves, a layer of insulation from the raucous, confusing world of our parents. But there was something seductive about that world, too, with its laughter and teasing; its music, theater, and books; the screaming parlor games; the elegance of smoking.

We lived in a duplex in the Osborne, a nineteenth-century apartment building on West 57th Street that had, by the 1950s, acquired a patina of sooty grandeur. Alexander and I spent little time in the downstairs spaces: the living room, with its wall of smoked mirrors and pair of nested brown pianos; the connecting library, with its clunky television console; or the studio off the front hall, where Daddy worked. We never ate dinner with the grownups in the formal dining room. Our domain was in the kitchen, where we had all our meals, and in our bedroom upstairs, with our toys and games, and our record player with the fuzzy animal decals on the sides.

In the evenings, after Rosalia, the cook, gave us dinner and our nanny, Julia, bathed us upstairs, my brother and I were brought in our bathrobes to the library, where our parents would be having before-dinner drinks with their friends. All the grownups would make a lovely fuss over us. Daddy would let Alexander open and close his Zippo lighter: shhhuppp, shhhuppp; Mummy would peel the thin red cellophane ribbon off her fresh pack of Chesterfields, expertly zip the ribbon between her thumb and fingernail, and crimp it into a little corkscrew to tuck behind my ear. Alexander would perform silly dances, while I stood on the arm of the sofa giving loud, arm-waving speeches in gibberishimitating the man with the brushy little moustache and plastered-down hair whose occasional appearances on the library TV always wiped the smiles off the grownups faces. They would explain to me in oddly tense tones that he was a very bad man. But they enjoyed my impersonation, cheering lustily after each of my fiery cadences.

Too soon, Julias starched white uniform would materialize in the doorway, signaling it was time for us to go to bed. Kisses all around, good night, good night! our mother would trill. But we never wanted to leave. Finally, Mummy would warn us that if we didnt cooperate, wed have to be taken a la fuerza, by force. I thought the phrase meant that Id be sent to a hellish place of punishment: I dont want to go to the fuerza! I would scream, kicking Julias shins as she dragged me upstairs. (The next day, shed point accusingly at her bruises: Look what you did to me!)

In the glow of the nightlight, Alexander and I lay in our beds, listening to the grownups carrying on downstairs. We sailed into slumber on the waves of their revelry: the tinkling of ice plopping into glasses, the roaring of songs around the piano. We knew it had to be our father at the piano, with the others clustered around him. It seemed as if all grownups ever did was have fun, with Daddy as their audible ringleader.

Dont drop him! The family in the Osborne.

Our mother, Felicia, would be right beside him at the piano. Petite and elegantly beautiful, with a long, swan-like neck, she had grown up in Chile, the middle daughter of Chita, an aristocratic Costa Rican, and Roy Cohn, an American mining engineer. (No relation to the nefarious Roy Cohn of the McCarthy hearings.)

Felicia Cohn was a wild spirit; Chile was too small and provincial to contain her. In her twenties, she was allowed to move to New York to study piano with her fellow Chilean, the eminent pianist Claudio Arrau. But upon arrival, Felicia shifted to an acting career, which likely had been her plan all along. She lived in a basement apartment in Greenwich Village with her dog, Nebbish. It was 1946, Felicia was twenty-fourand thats when she met Leonard Bernstein.

We often heard the story: There was a joint birthday celebration for Felicia and Claudio Arrau. Lenny Bernstein, the brash, handsome young musician everyone was talking about, showed up at the party. Bernstein had been in the news ever since his nationally broadcast conducting debut with the New York Philharmonic three years earlier: at age twenty-five, hed stepped in for the flu-stricken maestro, Bruno Walter, in Carnegie Hallan event that made the front page of the New York Times. Soon after, Bernstein made a double splash as a composer: first with his ballet Fancy Free, about three sailors on the loose in New York City, and then with