This book is dedicated to the memory of

HUW WHELDON (19161986)

my mentor and friend at BBC Television for twenty years.

It was in his ebullient company that

I first met Leonard Bernstein.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

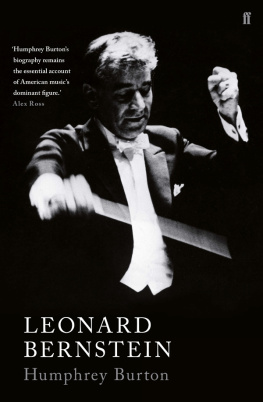

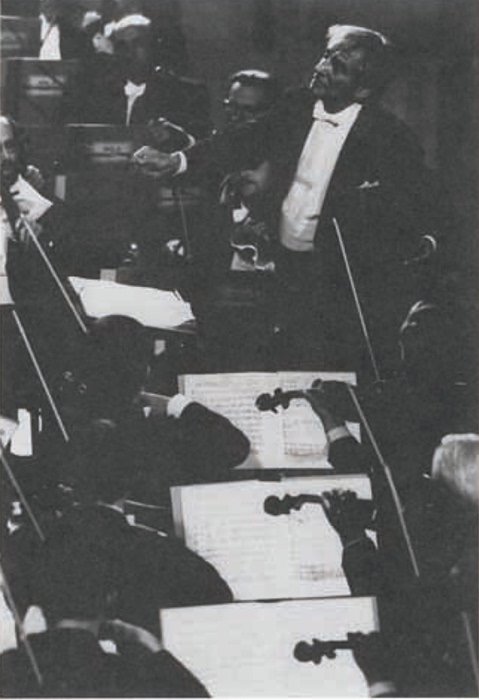

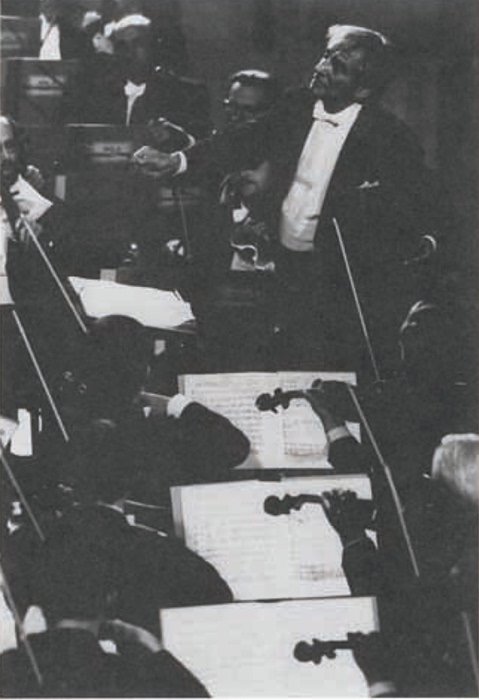

In full Mahlerian embrace, with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra in 1974. They had become the vessel for something holy.

PHOTO UNITEL/LAUTERWASSER

What a head start I had on any conventional biographer! I was discreet about my closeness to Leonard Bernstein, restricting myself to footnotes such as The author was present on this occasion, but as his regular film director I was intimately involved with Bernstein and his worlds for twenty-five years. I sat in on his rehearsals and filmed his performances some cameras concentrating on intense close-ups, others on his expressive, almost balletic body language as he gave his all to great orchestras and student players alike. Starting in Chichester Cathedral in 1965, I attended many of his premieres, including his last musical, his second opera and his Concerto for Orchestra, one of whose movements a set of variations he dedicated to my daughter Helena and myself: to H.B. and H.B. I watched his children grow up and played the mad intricate word games that were an essential element of Bernstein family parties. Through our long years of collaboration, my life was irrevocably changed: the least I could do by way of repayment after his death was to write his biography.

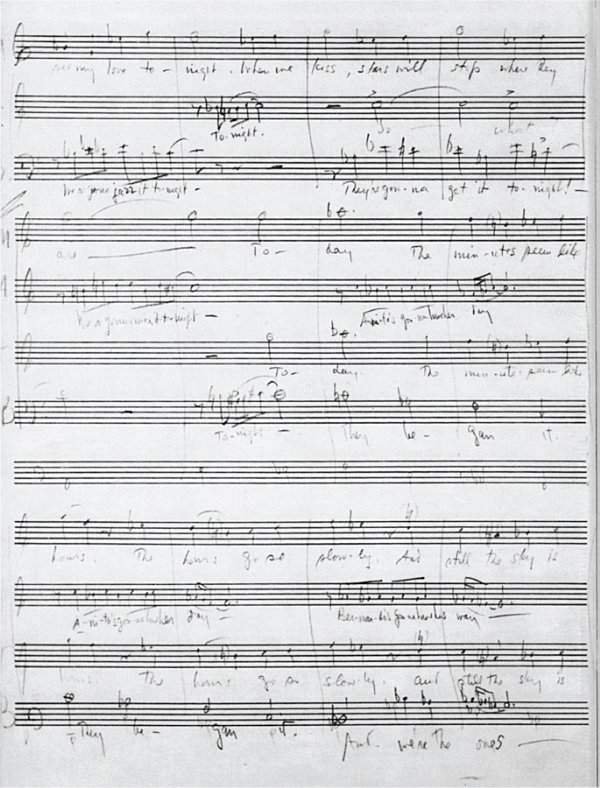

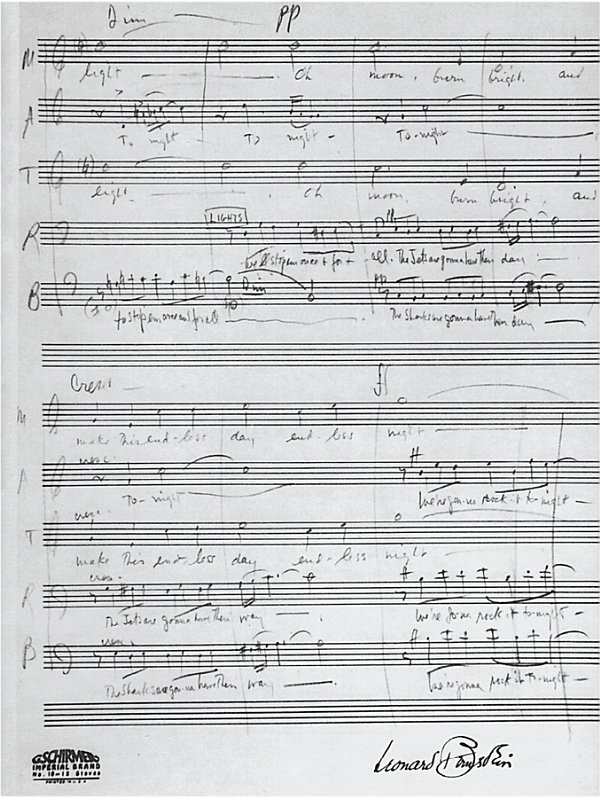

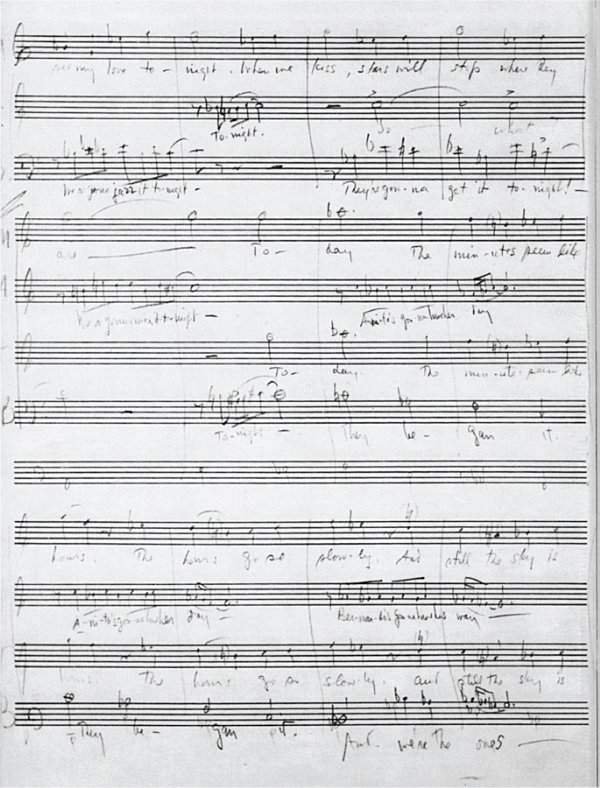

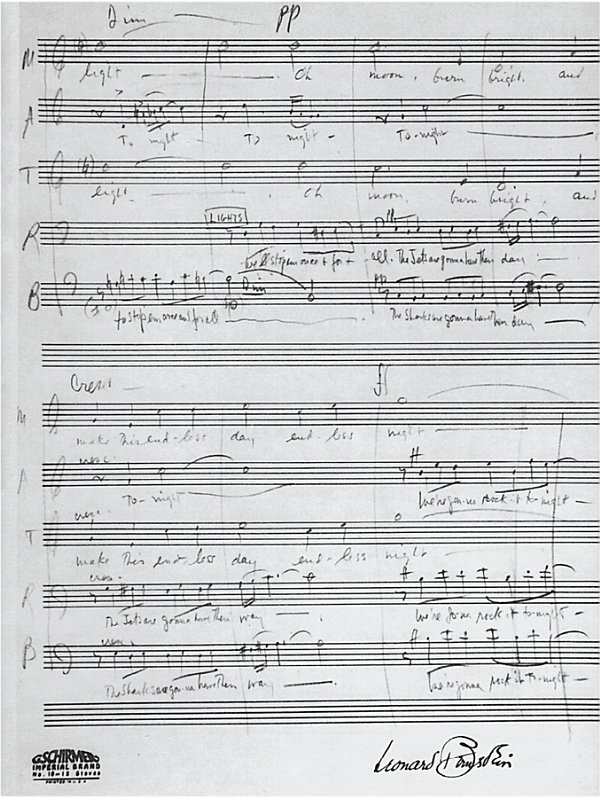

Leonard Bernstein (henceforward Bernstein, never Lenny) died on 14 October 1990. When this book was being written, I was given exclusive access to the Bernstein Archive, which in those days was mostly stored in a warehouse in Chelsea, near the Hudson river, on the same floor, curiously enough, as the archive of another American icon, Andy Warhol. Other documents were piled on the shelves of a tiny room in the Osborne building, opposite Carnegie Hall, in the former office of the late Helen Coates, Bernsteins devoted secretary (and chief hoarder), for close on half a century. They were in the process of being catalogued. But there was already a significant deposit of musical manuscripts and other Bernstein material at the Library of Congress in Washington, and today that noble institution houses the Leonard Bernstein Collection. Consisting of over 400,000 items, it is among the librarys largest and most frequently consulted archives, and substantial sections are now available online for anyone to read. YouTube is also helpful for the general reader: performances of several Bernstein compositions (and clips from many more) can be accessed in seconds. Archive sound recordings of his music going back to 1943 can be retrieved from cyberspace via such inexpensive platforms as Spotify and Apple Music, and his principal record companies, Deutsche Grammophon and Sony, continue to repackage CDs of his innumerable orchestral recordings of his own works, those of his American contemporaries, and the core classical repertoire down to Mahler and twentieth-century masters such as Bartk and Stravinsky. Another visual tool that can be used in conjunction with this biography is the extensive corpus of Bernsteins concert films, available as commercial videos. A recent development has seen the mounting of live orchestral performances to accompany screenings in large halls of the Bernstein film classics On the Waterfront and West Side Story.

Now for a survey of the twenty-first-century research. To begin at the beginning with Bernsteins childhood: no subsequent account can match for authenticity Family Matters, his brother Burtons masterly 1982 memoir, but a great deal of detail has since been unearthed concerning such topics as the music-making at his Boston synagogue and the entertainments the teenage Bernstein mounted at the family summer home in Sharon, Massachusetts. The fruits of this study are in Leonard Bernsteins Jewish Boston, by Sarah Adams and other Harvard students, in the Journal of the Society for American Music, issued in 2009. Other researchers concentrate on his life at Harvard and in particular the production of The Birds, for which he wrote his first substantial music-theatre score. Claudia Swan was the editor of Leonard Bernstein: The Harvard Years (New York, The Eos Orchestra, 1999).

Our knowledge of Bernsteins first years in New York received a jolt in 2011, when his estate released more than two thousand letters that had been sealed in a bank vault (by his manager, Harry Kraut) for two decades. Mark Horowitz, one of the senior music specialists and effectively the curator of the Leonard Bernstein Collection, recently informed me that a significant portion relates to Bernsteins homosexuality including letters from over 40 male romantic encounters; many of these are extraordinary, revealing so many aspects of gay history. In my experience they can be shocking, too: Harold Lang, one of the dancers in Fancy Free, writes to Bernstein regretting he has no photograph but adds, I still have the bite-marks. Maybe it was a joke.

Moving swiftly on to Bernsteins composing life, there is still no general study devoted to his orchestral works we have to rely on the individual LP and CD sleeve notes written by Jack Gottlieb and approved by the composer. But the Broadway shows and the two operas have been explored in detail by the English writer Helen Smith in Theres a Place for Us (Ashgate, 2011). The origins of Bernsteins first two ballets, Fancy Free and Facsimile, form part of a forthcoming book entitled Bernstein and Robbins by Sophie Redfern. She reveals the midwife role played by the designer Oliver Smith, who bullied young Bernstein into composing in double-quick time the Facsimile score for which another composer had already been hired and had to be paid off.

Bernsteins annus mirabilis, 194344, has been lovingly opened up by the Harvard music professor Carol J. Oja, who has devoted an entire book to just one musical, On the Town. Ms Ojas self-explanatory title is Bernstein Meets Broadway (Oxford University Press, 2014) and, as well as analysing what George Abbott teasingly called that Prokofiev stuff, the study adds greatly to our knowledge of how Bernstein and his good companions broke into New Yorks show-business world in 1944, and broke many conventions while doing so. Thus On the Town frequently challenged the colour bar, and was the first show to employ an African American musician, Everett Lee, to conduct a white orchestra on Broadway. Ojas subtitle, Collaborative Art in a Time of War, indicates the fascinating details her research has revealed. She reports, for example, on how the FBI was sniffing around the heels of Bernsteins left-leaning colleague Jerome Robbins and their Japanese star dancer, Sono Osato.

The extent of Bernsteins decades-long surveillance by the Federal Bureau of Investigation is the most explosive topic in recent biographies. When writing this book, just after Bernsteins death, my goal was to provide a rounded portrait of his creative and personal life. Inevitably politics came into the narrative played in Bernsteins daily life, but he catches the ghastliness of the McCarthy witch-hunt and he is spot-on in reminding us that Bernstein remained a left-wing progressive throughout his life liberal and proud of it, as he told the

Next page