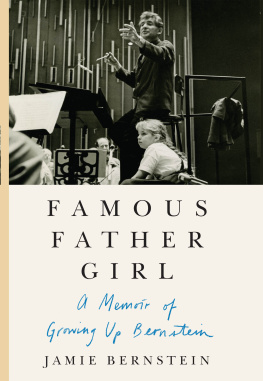

LEONARD BERNSTEIN

Leonard Bernstein

An American Musician

ALLEN SHAWN

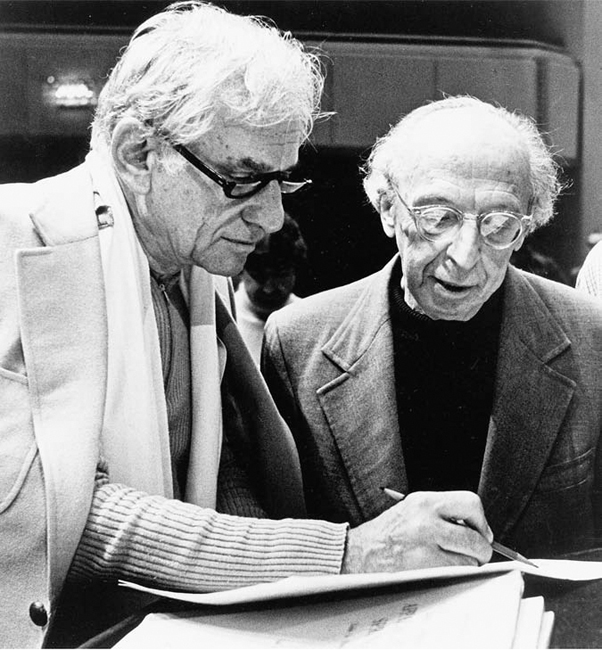

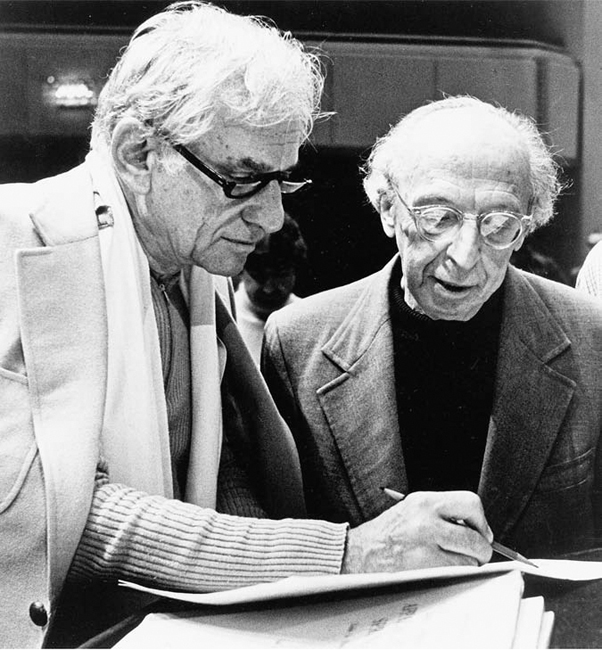

Frontispiece: Leonard Bernstein (left) and Aaron Copland, April 1981.

Photograph courtesy of Photofest.

Copyright 2014 by Allen Shawn.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S.

Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu

(U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN: 978-0-300-14428-4 (cloth)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014941713

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Yoshiko

Books by Allen Shawn

Arnold Schoenbergs Journey

Wish I Could Be There

Twin

CONTENTS

Introduction

SHOSTAKOVICHS FIRST SYMPHONY, written when he was nineteen, begins with a quiet, sarcastic-sounding little tune on muted trumpet, soon accompanied by a bassoon pecking out a droll counterpoint. Then two oboes join the bassoon for a short phrase in unison rhythm that peters out after seven beats. There is a pause, and a jocular clarinet breaks the silence with a brash upward run and a melody that is a mocking variant of the opening trumpet tune. Then the strings join in, and the movement is truly under way.

Leonard Bernstein is rehearsing an orchestra of young musicians at the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival. It is summer 1988. In a month he will turn seventy. He is seated, chatting about the work. He is wearing dark glasses and a loose-fitting sky-blue shirt over a white T-shirt. Although he smiles frequently, there is a weariness in the set of his mouth and in the gravelly sound of his voice. The musicians themselves are not much older than Shostakovich was when he wrote this work, but it is Bernstein who is telling them about its wonders and paradoxes. He speaks about Shostakovichs antiauthoritarianism, about how quirky and unheroic the symphonys opening is, about its takeoffs on Wagners Tristan, about how its first gestures end in sarcastic shrugs. He emphasizes that in the first and second movements the playing must be terse and witty so as not to anticipate that, in the Lento which follows, parody will give way to overflowing romantic feeling, unmasking the clipped diffidence of the opening of the work to reveal the intensity, the love of the very music it is rebelling against, behind it. He talks about an extraordinary place in the slow movement that is the most mysterious moment in the work. The sound in the strings must be as soft as humanly possible, yet also urgent. The only way to achieve this is to play with practically no bow at all, but with the fastest possible vibrato. It is as if, Bernstein seems to be saying, the music captures what Shostakovich was at that moment, what he was leaving behind, and what he would becomeall in one work.

Bernstein speaks like an old scholar, immersed in a text, who suddenly looks up and starts to talk about it. Although he is, in fact, an old scholar, he doesnt look precisely old. It is more as if he were young but tired, perhaps even tired of being himself. At the same time there is nothing resigned or routine in his bearing. He speaks of the score with the greatest immediacy, conveying excitement about every detail on the page.

He raises his hands to begin the symphony, and instantaneously there is discipline, a spring and economy in his gestures, an irresistible inner rhythm. The tinny trumpet tune sounds, the bassoon joins in; he brings down his arms in tiny increments, one for each beat, as the two oboes and bassoon make their unison diminuendo, then makes a brusque upbeat for the bawdy clarinet entrance. He soon stops the clarinetist, a young woman: No, noforte, he says. Really. They start again, and again stop. Surprise us.... Come. They start once more. No, but on the right beat, he says with mild irritation, pausing. Dont look so scared. Come on, just play the scale forte. One before 1. He calls out vigorously: One, two, three!... Atta girlgood. But then he stops again. Its not forte. Why arent you playing forte? Then he asks gently, Why are you so frightened? Although there is an audience watching the rehearsal and a film crew filming it, and there are a hundred musicians onstage, the moment feels private. He smiles, his hands come together. Forte. Loud. Loud. Come on, and stay forte for four bars. Atta girl; good. Pausing again: You see, in the last bar it comes down to mezzo forte. When the bassoon joins you, she has to join you mezzo forte. And she comes in sounding louder than you because youve already gotten to piano. I dont know why you are so shy. Is it just today? (She shrugs.) Youre not a shy girl, right, by nature? He sings out her clarinet line boisterously. Do every note the sameforte. Then in a slightly self-caricaturing tone he counts One, two, three and cues her. The passage sounds much better. He looks buoyant.

At the performance a week later, now dressed in his concert tuxedo and white bow tie, he is guiding the players through the score, giving signs little and big to remind them of everything they had worked on in rehearsal. In one sense the music is now in their hands. But he is controlling the journey, like a pilot steering an ocean liner, and there is enormous concentration and tension in his body. By the close of the last movement he is bathed in sweat, and he can hardly keep his eyes open for the rivulets of water streaming down his face. There is an ovation. He waits for several moments, seems to gasp for breath while a look of exhaustion passes over him, then nods to the players with satisfaction. Not yet turning to the audience, he hugs the concertmaster and first cellist. They suddenly look like boys, bashful, moved. He motions to the orchestra to rise, then finally turns and bows. On the way to the back of the stage he takes the hand of the clarinetist in passing, and she smiles. Returning toward the stage, he acknowledges the timpanist, then the first oboist, then motions for the clarinetist to rise and holds her hand up. She blushes. As he returns to the podium his face is gray with fatigue for a moment; he points with pride to the concertmaster and the first cellist, who stand. He bows; he receives flowers from a girl wearing a white dress with a red-and-green floral print on it and kisses her hand. He motions for the orchestra as a whole to rise again, bows and turns to them, throwing the flowers out one by one, and then as a bunch. For a moment Bernstein looks not seventy, but forty. He leaves the stage again and returns again, this time acknowledging the bassoonist and the pianist and reaching over one more time to congratulate the clarinetist. The pianist puts a flower in his lapel. As if suddenly seeing the moment as she will remember it years from now, the second oboist puts her head in her hands; a violinist looks down sadly, lost in thought, holding her violin and a flower together, her blond hair hanging over her face. Bernstein makes a gesture to the orchestra like a prizefighter at the end of a fight. The audience continues to applaud.

Next page