King Leopolds Ghost

A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa

Adam Hochschild

A MARINER BOOK

Houghton Mifflin Company

BOSTON NEW YORK

FOR

DAVID HUNTER

(19162000)

F IRST M ARINER B OOKS EDITION 1999

Copyright 1998 by Adam Hochschild

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hochschild, Adam.

King Leopolds ghost : a story of greed, terror, and heroism in

colonial Africa / Adam Hochschild.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-395-75924-0 ISBN -13: 978-0-618-00190-3 (pbk.)

ISBN -10: 0-395-75924-2 ISBN -10: 0-618-00190-5 (pbk.)

1. Congo (Democratic Republic)Politics and government

18851908. 2. Congo (Democratic Republic)Politics and

government. 3. Forced laborCongo (Democratic Republic)

History19th century. 4. Forced laborCongo (Democratic Republic)

History20th century. 5. Indigenous peoplesCongo (Democratic

Republic)History 19th century. 6. Indigenous

peoplesCongo (Democratic Republic)History20th century.

7. Congo (Democratic Republic)Race relationsHistory19th

century. 8. Congo (Democratic Republic)Race relationsHistory

20th century. 9. Human rights movementsHistory 19th century. 10.

Human rights movementsHistory20th century.

I.Title.

DT 655. H 63 1998

967.5 dc21 98-16813 CIP

Printed in the United States of America

QUM 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14

Book design by Melodie Wertelet

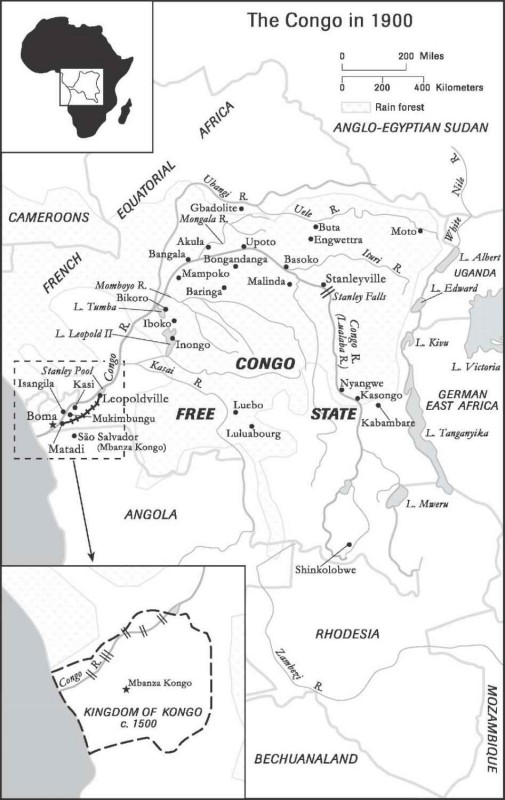

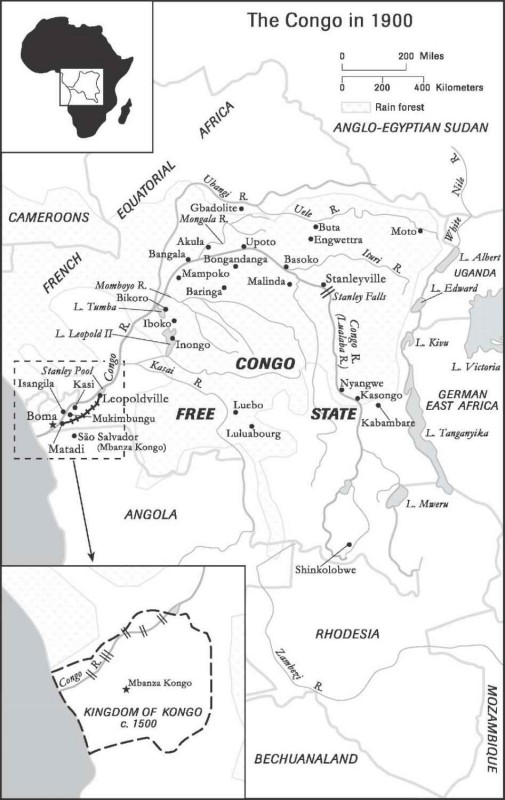

Map by Barbara Jackson, Meridian Mapping, Oakland, California

Photo credits appear on .

In somewhat different form, portions of chapters 9 and 19 appeared in The

New Yorker, and portions of chapters 5 and 16 in The American Scholar.

CONTENTS

Introduction

Prologue: The Traders Are Kidnapping Our People

PART I: WALKING INTO FIRE

1. I Shall Not Give Up the Chase

2. The Fox Crosses the Stream

3. The Magnificent Cake

4. The Treaties Must Grant Us Everything

5. From Florida to Berlin

6. Under the Yacht Club Flag

7. The First Heretic

8. Where There Arent No Ten Commandments

9. Meeting Mr. Kurtz

10. The Wood That Weeps

11. A Secret Society of Murderers

PART II: A KING AT BAY

12. David and Goliath

13. Breaking into the Thieves Kitchen

14. To Flood His Deeds with Day

15. A Reckoning

16. Journalists Wont Give You Receipts

17. No Man Is a Stranger

18. Victory?

19. The Great Forgetting

Looking Back: A Personal Afterword

Notes

Bibliography

Acknowledgments

Index

INTRODUCTION

T HE BEGINNINGS of this story lie far back in time, and its reverberations still sound today. But for me a central incandescent moment, one that illuminates long decades before and after, is a young mans flash of moral recognition.

The year is 1897 or 1898. Try to imagine him, briskly stepping off a cross-Channel steamer, a forceful, burly man, in his mid-twenties, with a handlebar mustache. He is confident and well spoken, but his British speech is without the polish of Eton or Oxford. He is well dressed, but the clothes are not from Bond Street. With an ailing mother and a wife and growing family to support, he is not the sort of person likely to get caught up in an idealistic cause. His ideas are thoroughly conventional. He looksand isevery inch the sober, respectable businessman.

Edmund Dene Morel is a trusted employee of a Liverpool shipping line. A subsidiary of the company has the monopoly on all transport of cargo to and from the Congo Free State, as it is then called, the huge territory in central Africa that is the worlds only colony claimed by one man. That man is King Leopold II of Belgium, a ruler much admired throughout Europe as a philanthropic monarch. He has welcomed Christian missionaries to his new colony; his troops, it is said, have fought and defeated local slave-traders who preyed on the population; and for more than a decade European newspapers have praised him for investing his personal fortune in public works to benefit the Africans.

Because Morel speaks fluent French, his company sends him to Belgium every few weeks to supervise the loading and unloading of ships on the Congo run. Although the officials he works with have been handling this shipping traffic for years without a second thought, Morel begins to notice things that unsettle him. At the docks of the big port of Antwerp he sees his companys ships arriving filled to the hatch covers with valuable cargoes of rubber and ivory. But when they cast off their hawsers to steam back to the Congo, while military bands play on the pier and eager young men in uniform line the ships rails, what they carry is mostly army officers, firearms, and ammunition. There is no trade going on here. Little or nothing is being exchanged for the rubber and ivory. As Morel watches these riches streaming to Europe with almost no goods being sent to Africa to pay for them, he realizes that there can be only one explanation for their source: slave labor.

Brought face to face with evil, Morel does not turn away. Instead, what he sees determines the course of his life and the course of an extraordinary movement, the first great international human rights movement of the twentieth century. Seldom has one human beingimpassioned, eloquent, blessed with brilliant organizing skills and nearly superhuman energymanaged almost single-handedly to put one subject on the worlds front pages for more than a decade. Only a few years after standing on the docks of Antwerp, Edmund Morel would be at the White House, insisting to President Theodore Roosevelt that the United States had a special responsibility to do something about the Congo. He would organize delegations to the British Foreign Office. He would mobilize everyone from Booker T. Washington to Anatole France to the Archbishop of Canterbury to join his cause. More than two hundred mass meetings to protest slave labor in the Congo would be held across the United States. A larger number of gatherings in Englandnearly three hundred a year at the crusades peakwould draw as many as five thousand people at a time. In London, one letter of protest to the Times on the Congo would be signed by eleven peers, nineteen bishops, seventy-six members of Parliament, the presidents of seven Chambers of Commerce, thirteen editors of major newspapers, and every lord mayor in the country. Speeches about the horrors of King Leopolds Congo would be given as far away as Australia. In Italy, two men would fight a duel over the issue. British Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, a man not given to overstatement, would declare that no external question for at least thirty years has moved the country so strongly and so vehemently.

This is the story of that movement, of the savage crime that was its target, of the long period of exploration and conquest that preceded it, and of the way the world has forgotten one of the great mass killings of recent history.

***

I knew almost nothing about the history of the Congo until a few years ago, when I noticed a footnote in a book I happened to be reading. Often, when you come across something particularly striking, you remember just where you were when you read it. On this occasion I was sitting, stiff and tired, late at night, in one of the far rear seats of an airliner crossing the United States from east to west.

The footnote was to a quotation by Mark Twain, written, the note said, when he was part of the worldwide movement against slave labor in the Congo, a practice that had taken eight to ten million lives. Worldwide movement? Eight to ten million lives? I was startled.

Next page