The Characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

First published in 2002 by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.

Anniversary Edition Copyright 2013 by Pagan Kennedy

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express permission of the publisher or author.

Published by SFWP

369 Montezuma Ave

#350

Santa Fe, NM 87501

www.sfwp.com

Find the author at www.dangerousjoy.com and www.pagankennedy.net

To my sister

who worked to prevent famine in Angola,

stayed as the country collapsed,

and evacuated only when bombs began to fall

THE CROSS

God laid upon my back a grievous load,

A heavy cross to bear along the road;

I staggered on, till lo! One weary day,

An angry lion leaped across my way.

I prayed to God, and swift at His command

The cross became a weapon in my hand;

It slew my raging enemy, and then

It leaped upon my back a cross again!

I faltered many a league, until at length,

Groaning, I fell and found no further strength,

I cried, God! I am so weak and lame,

And swift the cross a winged staff became.

It swept me on until I retrieved my loss,

Then leaped upon my back again a cross.

I reached a desert; on its burning track

I still perceived the cross upon my back.

No shade was there, and in the burning sun

I sank me down and thought my day was done;

But Gods grace works many a sweet surprise.

The cross became a tree before mine eyes.

I slept, awoke, and had the strength of ten,

Then felt the cross upon my back again.

And thus through all my days, from that to this,

The cross, my burden, has become my bliss;

Nor shall I ever lay my burden down,

For God shall one day make my cross a crown.

William Henry Sheppard

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

I met William Henry Sheppard in a book. Though hed been dead seventy years and now consisted of nothing but a few pages of text in a well-thumbed paperback, he swept into my life with all the urgency of a new lover. The book in question was Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo by Harvey Blume and Phillips Verner Bradford. Sheppard was only a minor character in the nonfiction epic, and truthfully the authors could have left him out if they had wanted tohe was tangential to their story.

But what author could pass up a character like William Sheppard? At the turn of the century he had traveled deep into the Congo jungle in search of the hidden kingdom. Once he found his way into the capital citythe first Westerner ever to do sohe was hailed as a reincarnated prince by its people.

The story had all the hallmarks of an MGM movie from the 1930san Afrocentric retelling of Lost Horizon, perhaps. And it was only the first episode in Sheppards incredible lifethe prelude to his trips to the White House, his one-man intervention in a massacre, his international fame as a witness against the atrocities of the Belgian regime. I had to know more about this astonishing, lost herothis black American missionary. But when I searched him out, I discovered that little had been written about Sheppard. He appeared now and then in books about the Congo, but always as one character among many, like a blurry face in a group photo.

I kept thinking he should have his own book, and I assumed someone else would write it someday. The author would be an Africa specialist with a flair for embellishment, preferably a man, preferably an African American. He would work on the book during his sabbatical from Harvard, getting graduate students to help him with the extensive research; hed travel to the Congo, retrace Sheppards steps. I certainly was not equipped to take on the job; and as a white woman I wasnt sure that I had the insight to portray a black man during the Jim Crow period. Furthermore, I felt uncomfortable about intruding into African American history.

Eventually, I discovered that Sheppard did have his own bookan autobiography, of sorts. The copy of it that I managed to track down was a slim volume, rebound some years back to protect its decaying spine, little more than a tract, called Presbyterian Pioneers in Congo. It was put out by the church in 1917.

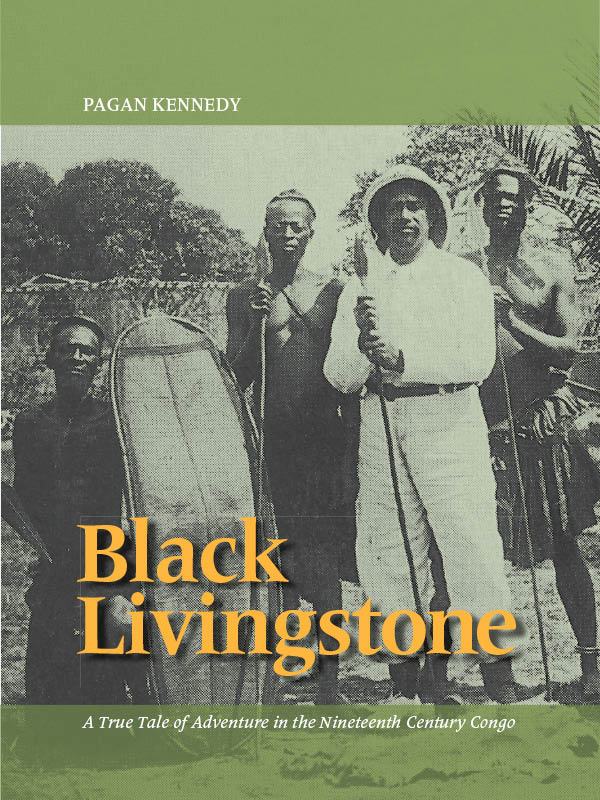

Here he was, the real Sheppardin his own words. I read the whole book at a coffee shop next to the library, the chatter and clatter of the place drowned out by Sheppards humorous, fanciful prose. The book had been adapted from the lectures he gave when he toured the country in the 1890s and again in the 1910s, when he billed himself as Black Livingstone, an explorer returned from Africa. To understand what the book is like, you have to imagine him pacing on the stage before a meeting hall strung with newfangled electric lights, charming a crowd (the blacks up in the balcony, the whites down front). He coaxes them into laughter, and then suddenly swoops into tragedy, prompting more than a few ladies to pull out linen hankies. Sheppard knows himself to be a great entertainer and a great curiositya man whos survived Africa (few went, and one out of three did not make it home). Hes returned with anecdotes about crocodile attacks and bronze-colored queens, tattooed faces and filed teeth. It is the era of Horatio Alger and Booker T. Washington, of snake oil and Chautauqua, of steam and coal and vast, humming machines, of magical exhibitions and the miracle of new wealth. It is also the era of Jim Crow.

In his book, Sheppard tiptoes around race issues, and who can blame him? In the first year he went on the speaking circuit, more than a hundred blacks were recorded as lynched. So Sheppards account of his childhood in America is, above all, polite. But when he describes Africa, his prose changes; he suddenly shifts into high gear, becoming fable-ist, fabulist, and picaresque hero. He tells how eating eggs helped him to navigate the secret trails of Africa. He displays the African executioners knife that was nearly used on his own neck. He seduces his audience with exotica: An engraving shows Luebo as it would have appeared to Sheppard and Lapsley when they first arrived in 1891.We saw a rain-makerdressed up in leopard skins and his hair filled with hawk feathers, and in his hand were a buffalo tail and a sprig of a tree.

Indeed, Sheppard was a black Livingstone, a man caught between the nineteenth century and the twentieth, between white colonialism and black pride. Like Livingstone, the famous English missionary, he brought home an Africa scented with the perfume of palm winean exotic Beyond the Looking Glass, a mirror-image land. But unlike Livingstone, he often treated Congo culture as the equal of his own. He forced his audience to reckon with an idea that W. E. B. Du Bois would expand upon in 1946 when that leader wrote, Here is a history of the world written from the African point of view. Sheppard had stepped through the looking glass, gazed back at his own country through African eyes and begun to question which point of view was real.

I wondered who this marvelous man had been in private and what made him die of paralysis and apparent heartbreak at the age of sixty-one. Such mysteries drove me to special-order books from obscure libraries, books that arrived swaddled in beautiful jackets with little notes inside them: Very delicate condition. Use extreme care in handling.

I had to solve this puzzle. I had to understand him. Forand I couldnt say whyas I read Sheppards writings, I began to believe that he held a key to my own history. Perhaps he could answer the riddle that had dogged me ever since I was a girl: When you stripped off the hoop skirts and crinoline of my fathers illusions, who were we?