Africa in Global History

Edited by

Joel Glasman

Omar Gueye

Alexander Keese

Christine Whyte

Volume

ISBN 9783110708691

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110709308

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110709377

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2021 Daniel Tdt, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston // The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Funded by Humboldt-Universitt Berlin

Introduction

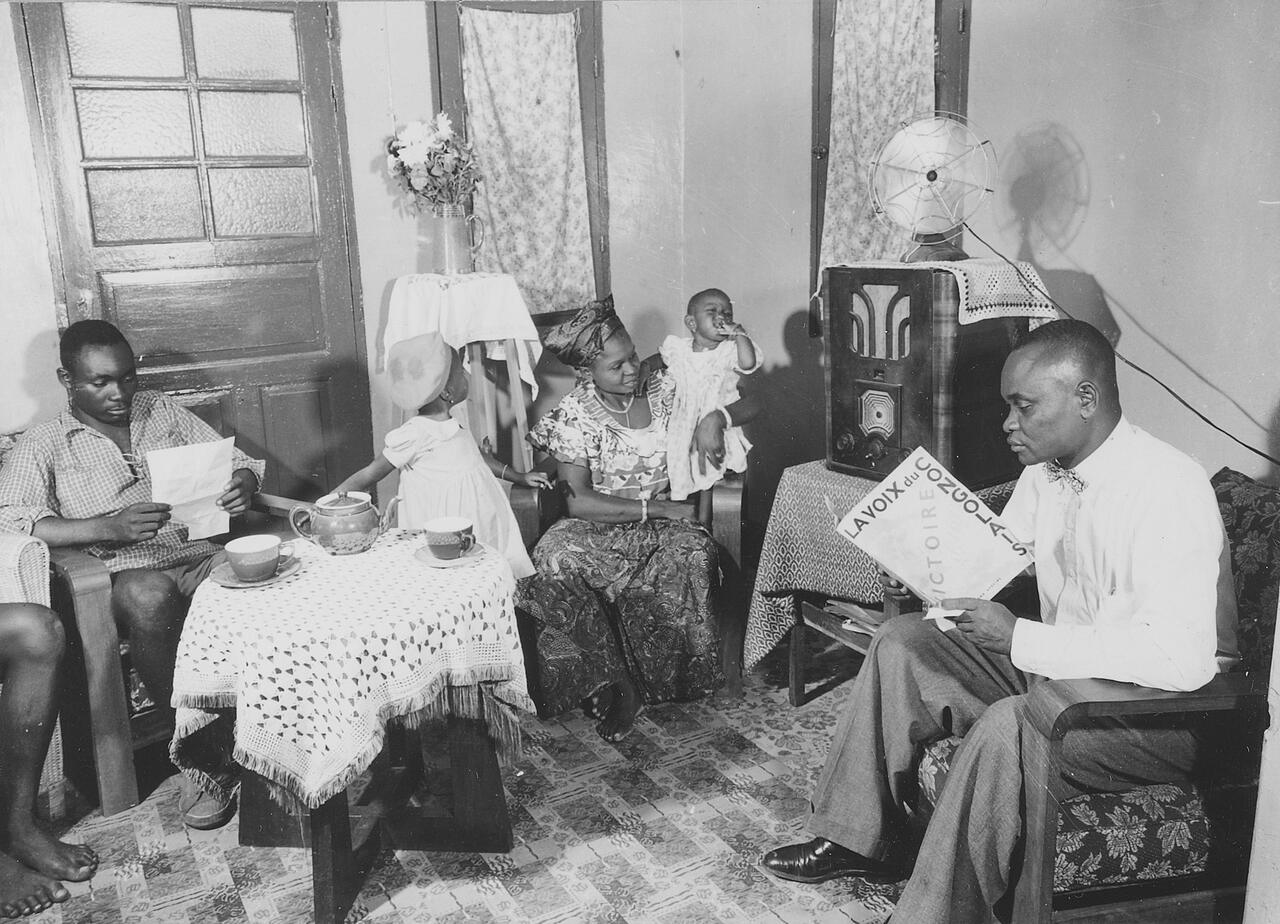

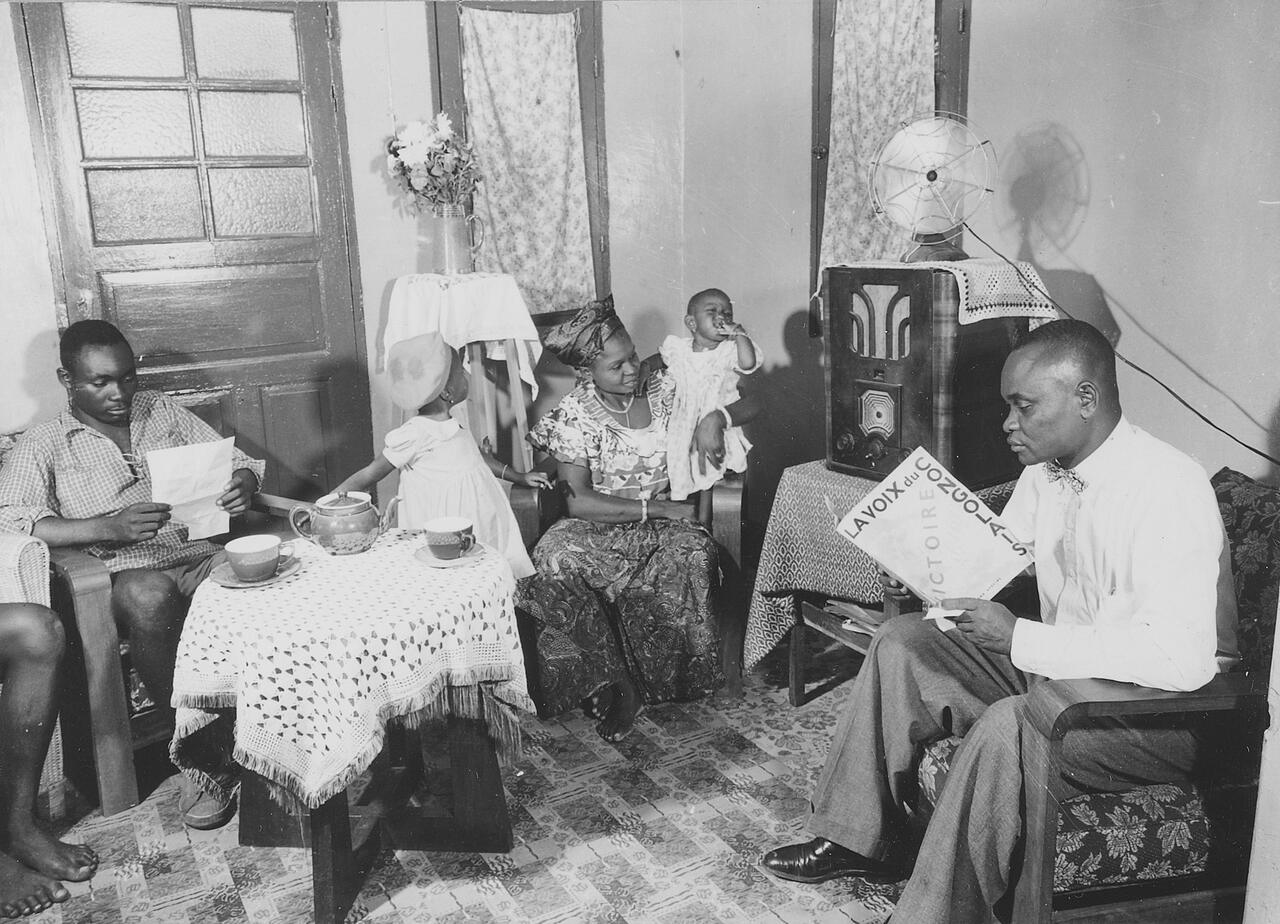

A photograph presents the bourgeois family idyll in Lopoldville. The father, sitting in an armchair in the foreground, dominates the living room scene. He is wearing a white shirt and tie, polished leather shoes and trousers with a crease in them. His elbows resting on the arms of the chair, he is engrossed in the Voix du Congolais, a newspaper for the vernacular elite published by the Belgian Congos General Government from 1945 onwards. In the centre of the picture but in the background, his wife, wearing a dress, is holding a baby in her arms. In front of her to the left there are two children: their daughter is standing with her face turned away from the camera, and their older son is also reading. The living room is equipped with a radio and a fan, while the tables are decorated with flowers and crocheted tablecloths. A tea service sits on the coffee table, around which the family members are arranged.

This photograph, commissioned by the General Governments Press and Propaganda Department in 1952 and titled A Family of Congolese volus in Lopoldville reveals what the Belgian colonial state viewed as exemplary and civilized family life within the framework of its elite-making. This is just one example of the countless photographs and articles relating to the model volu that circulated after the Second World War in the colonial public sphere. The so-called volus were a small but elite group of educated Congolese, During this period, the colonial state found itself compelled, for the first time, to set about forming a so-called African elite, and it defined this groups desirable features. What emerged was a highly idealized set of discourses and images steered by the colonial state, from which the volus had to take their lead if they were to be viewed as legitimate representatives of the elite. The colonial public sphere, particularly periodicals such as the Voix du Congolais, portrayed this new elite as much as they staged and guided it.

But upon closer inspection, the bourgeois idyll in the photograph turns out to be deceptive. At the left edge of the photograph, the body of one family member is cut off by the camera angle in such a way that all we see of this individual is an uncovered leg and bare feet. This disruption to the visual composition of the ideal family scene may reflect the photographers technical incompetence. For strait-laced European contemporaries, however, nakedness was one of the key criteria by which they affirmed their own civilizational superiority and colonized societies primitiveness and savagery. In a figurative sense, this element of the imperfect typifies a discourse of colonial distinction in which the volus, despite all the bourgeois culture on display, were interpreted as unfinished products of the civilizing mission and thus as unworthy of an improved legal status.

Regardless of all the rhetoric, the emergence of an educated Congolese elite was the last thing the Belgian colonial state wanted. As in other parts of colonial Africa, the inhabitants of the Belgian Congo were to be denied social participation, a political say, legal equality and positions of responsibility for as long as possible. No elite, no worries: this motto was a common thread running through European rule in Africa. But that contemporaries associated this principle with Belgian colonial policy reflects the euphemistic character of elite formation in the Congo. What it actually meant was denying people access to universities, in both metropole and colony, and the right to political participation, for far longer than in British and French territories. In the colonial state, such forms of social discrimination were backed by a legal system that institutionalized injustice. First and foremost, Africans and Europeans represented juridical classifications that corresponded with separate legal systems. It was thus legal to systematically impose repressive punishments and forced labour on Africans, subject them to violence and deny them freedoms and participation. As this legal segregation was in turn legitimized by supposedly differing levels of civilization, it is unsurprising that the Congolese elite sought to obtain a special status by highlighting their development. Those who wished, for example, to claim the legal privileges of elite status had, among other things, to demonstrate a blameless family life, as evident in the previously mentioned photograph. Yet within a racist colonial ideology, such upwardly mobile boundary-crossing within the colonial social order was a theoretical possibility at best. In the Belgian Congo, such social ascent was denied even to the elites due to their alleged inadequacies. In colonial Africa, elite formation was meant to prevent the formation of an elite.

That which was cut off only visually in the family photograph the bare feet evokes other images associated with the earlier reign of terror in the colonial Congo. The shocking photographs of the severed hands of Congolese who had failed to fulfil their quota of forced labour during the rubber harvest were the iconographic epitome of the exploitative and murderous Congo Free State, the private possession of Belgian King Leopold II between 1885 and 1908. An international campaign against the atrocities in the Congo, run mainly by missionaries, focused on the media dissemination of photographs of human suffering, ultimately triggering the transfer of the colonial territory to the Belgian state in 1908. While its propaganda foregrounded the development of modern residential districts, hospitals and primary schools, it failed to mention labour regimes and instruments of domination that stood in continuity with the Free State. And though the volus were extolled as perfect residents of the model colony after 1945, the violence, disenfranchisement and racist discrimination inherent in colonial rule continued to shine through here and there in staged photographs. We can no more separate the image of the volu family in the living room from this reality than we can the capital city of Lopoldville from the man it was named after. Both lead into the same darkroom of colonialism.

Fig. 1: The staging of an volu family in Lopoldville, 1952.

Vernacular elites and decolonization

The discrepancies between Belgian colonial propaganda and the lived experience of Congolese collided on 30 June 1960 before the eyes of a global public. At the Republic of the Congos independence celebrations, King Baudouin was the first to give a speech, in which he glorified independence as the final, crowning achievement of Leopold IIs brilliant plan and as an expression of his civilizing mission, a project tenaciously continued by the Belgian state. Newly elected prime minister Patrice Lumumba spoke next: