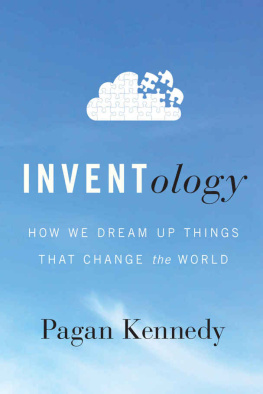

First Mariner Books edition 2016

Copyright 2016 by Pagan Kennedy

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kennedy, Pagan, date, author.

Title: Inventology : how we dream up things that change the world /Pagan Kennedy.

Description: First Mariner Books edition. | Boston : Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017. | An Eamon Dolan Book. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016041004 (print) | LCCN 2016045913 (ebook) | ISBN 9780544811928 (paperback) | ISBN 9780544324008 (hardback) | ISBN 9780544324015 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: InventionsHistory. | Creative ability in technology. | InventorsBiography.

Classification: LCC T 15. K 46 2017 (print) | LCC T 15 (ebook) | DDC 609dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016041004

ISBN 978-0-544-32400-8

Cover design by Mark R. Robinson

v2.1116

To my grandfather Stephen Patrick Burke, inventor

Introduction

In 2012, the New York Times Magazine hired me to write the weekly Who Made That? column, and so I began hunting down the people behind such inventions as sliced bread, the 3-D printer, and lipstick. Week after week, I discovered that ideas pop up wherever they please, and inventors come from every corner of life. A test pilot created aviator sunglasses; a frustrated father devised the sippy cup to foil his own toddler; and experiments in a kitchen in Queens, New York, led to the Xerox machine.

Why did these people hit on solutions that everyone else had missed? That question became a thread that I followed to an even bigger one: Is there a formula for invention, and if so, can anyone learn it?

So when I reached out to creative people for my column, I asked them about the process that had led them to conceive their bold ideas. One of the first people I queried, Jake Stap, taught me that sometimes we discover the power of our imagination only when we feel desperate. In the late 1960s, Stap worked as a coach at two Wisconsin tennis camps, and during those long days of lessons, he spent hours stooped over, retrieving hundreds of balls. His back ached, and he urgently needed to invent his way out of this drudgery.

Stap placed a tennis ball on the passenger seat of his car, where it rolled around for weeks, a reminder that he needed to think about the problem. As he drove, he performed mental experiments: he built an imaginary tennis court in his minds eye and pictured what it would be like to wear an arm extender that would let him reach the ground without bending over. But, he realized, the mechanical hand would pick up only one ball at a time. That was no good. Finally, during one of his meditations, Stap reached over and pinched the tennis ball on the seat next to him. When the rubber yielded under his fingertips, he had a new idea: the ball could squeeze through metal bars, taking a one-way trip into a wire bin.

Stap rigged up a basket with a handle and metal bars across its bottom so he could perform real-life experiments. I fooled around with the bars to find the right distance so that the balls would pop into the basket and stay there, he told me. He called his invention a ball hopper.

The next summer at tennis camp everyone wanted to use them, recalled his daughter, Sue Kust. It was a mad dash for the ball hoppers. She observed that when people saw how [the ball hopper] worked and how simple it was, they would always say, I could have thought of that.

His concept might have seemed obvious, and yet it wasnt. Rubber balls became standard tennis equipment in the 1870s, so by all rights, a Victorian gentleman should have used a wire basket to wrangle his tennis balls. Instead, for nearly a century, tennis players chased down the rubber balls without ever seeing Staps solution. Thats the mystery that surrounds some inventions. They seem easy in hindsight. And yet, the most elegantly simple breakthroughs can hide from us for decades. So what blocks us from grasping an idea? And how can we find the obvious ideas that are hiding from us right now?

To answer those questions, we must study many inventions and look for patterns. For instance, if you delve into the history of cancer cures, squirt guns, and smoke detectors, youll find startling similarities in the way that they came into existence. So if we can observe the techniques that have led lots of inventors to success, we might extrapolate what methods work best.

Invention versus Innovation

People tend to use the words invention and innovation interchangeably, which causes confusion. And so before we proceed any further, we should come up with working definitions for both. Art Frythe originator of the Post-it Notedeveloped his own way of distinguishing invention from innovation, and his definitions are so illuminating that I will borrow them and use them throughout this book. Invention, according to Fry, is what happens when you translate a thought into a thing. More specifically, Fry points out that an invention usually involves creating a prototype that lets you test your concept and demonstrate that it works. Once youve created that model, the creation becomes an invention, according to Fry. The process may require dreaming, drawing, observation, idea generation, discovery, tinkering, and engineering. But it should end with the proof.

Innovation is what happens afterward. It is the act of working through all of the obstacles and problems in the path of turning a creative idea into a business, according to Fry. Indeed, the term innovation is often used as a catchall word to describe the challenges companies must overcome in order to mass-produce a productlike streamlining, shaving costs, managing supply chains, and assembling teams of collaborators. The business side of product development is an art unto itself. But this book, for the most part, will not concern itself with business innovation.

Instead, we will investigate the first steps, the embryos, origins, and private visions that give birth to new things. As I spoke with inventors, they told me stories about hunting the original thought as if it were a rare bird flitting through the forest. The process often involves a craftsmanship of the imagination, in which we carry out experiments in our fantasies. When I get an idea I start at once building it up in my imagination. I change the construction, make improvements and operate the device in my mind, the visionary inventor Nikola Tesla wrote. He was describing a process of mental iteration that we all possessbut that too few of us have truly learned how to use.

Why We Need Inventology

This book will focus on what might be called micro-creativity, that is, invention at the level of the individual. Im not trying to advance what is known as the Great Man Theory, in which lone heroes are given sole credit for a breakthrough. Rather, it is an acknowledgment that you are one person, and so am I. While its interesting to find out which city generates the most patents per capita (Eindhoven, in the Netherlands, is often at the top of the list), that doesnt give us much insight into what we need to do, as individuals, to become more imaginative; after all, if you buy a plane ticket to Eindhoven and stroll along its charming canal, you likely wont be struck with genius.

Its crucial that we find out what people actually do as they invent things. What are they doing in their minds and with their hands? We need a new field of studycall it Inventologyto answer that question. If you aspire to run a marathon, you can read thousands of books on training for peak performance; you can pore over studies of the benefits of carb loading and wind sprints. But for those who aspire to invent, its much harder to find this kind of actionable research.

Next page