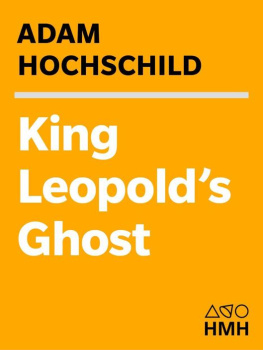

First Mariner Books edition 2007

Copyright 1990 by Adam Hochschild

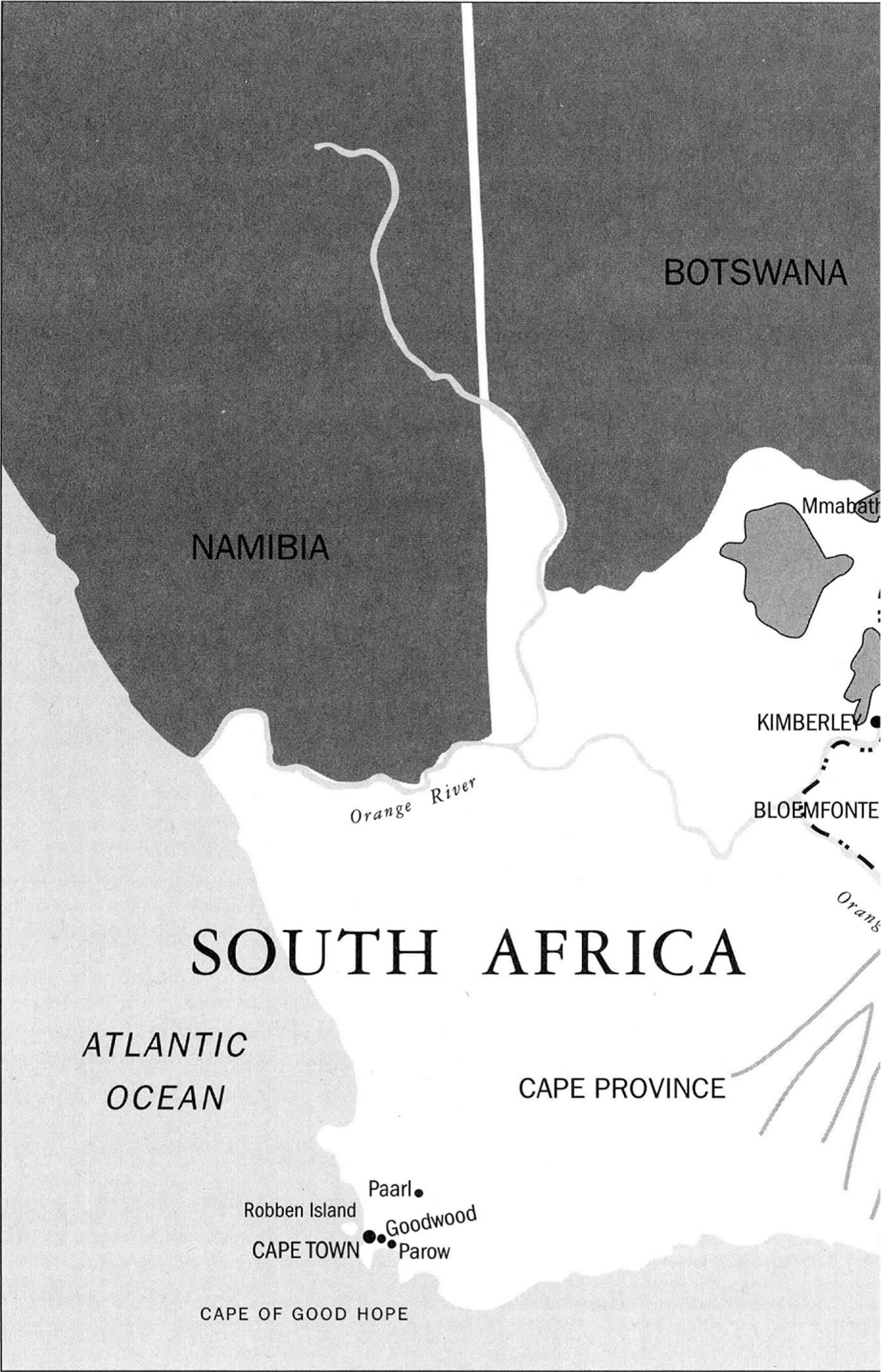

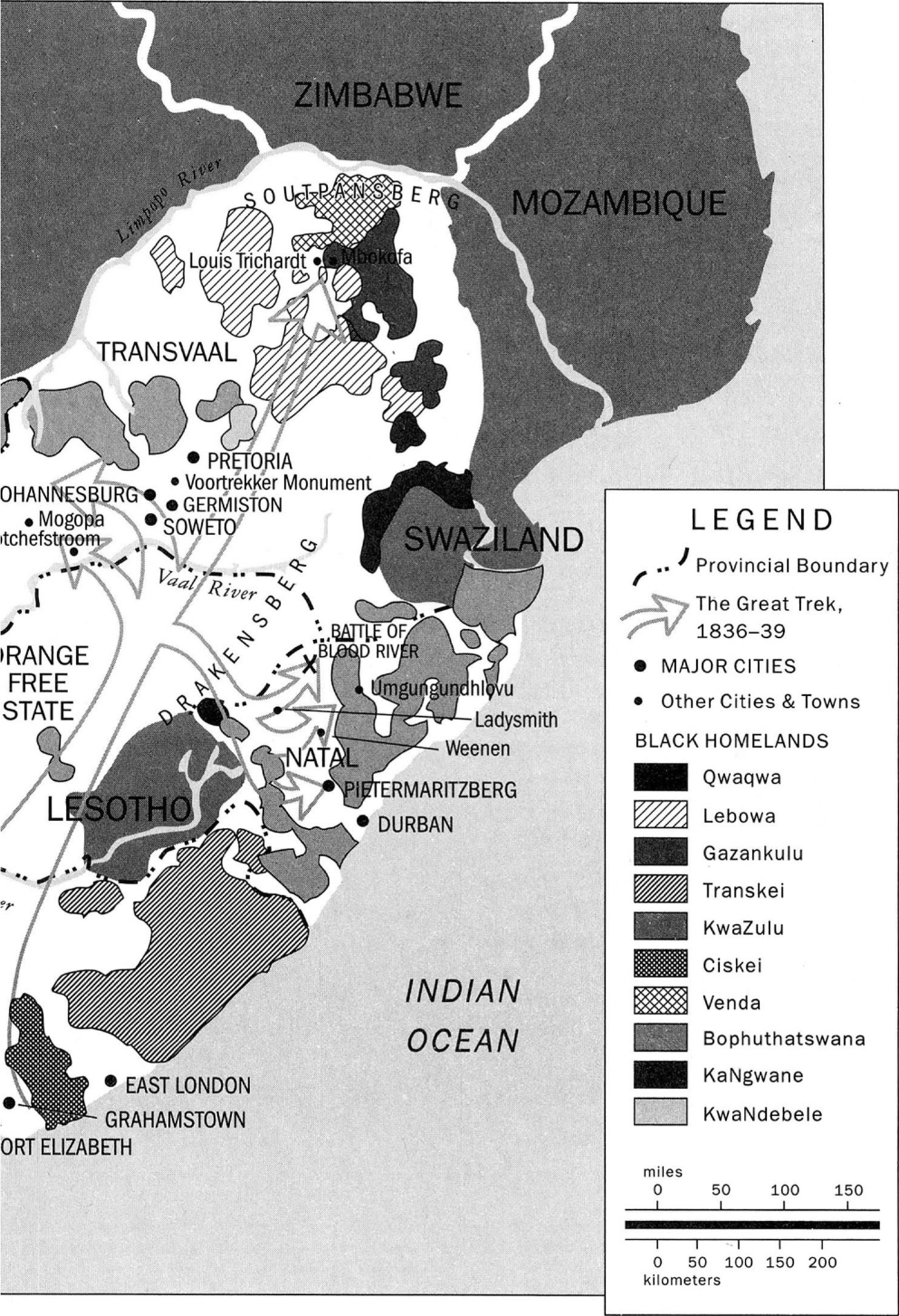

Map copyright 1990 by Viking Penguin,

a division of Penguin Books USA Inc.

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hochschild, Adam.

The mirror at midnight: a South African journey / Adam Hochschild.

1st Mariner Books ed.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Viking, 1990. With new preface

and epilogue.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN -13: 978-0-618-75825-8

ISBN -10: 0-618-75825-9

1. Blood River, Battle of, South Africa, 1838Anniversaries, etc.

2. AfrikanersRace identity. 3. South AfricaRace relationsHis

tory20th century. 4. Hochschild, AdamTravelSouth Africa.

5. South AfricaDescription and travel. 6. South AfricaSocial con

ditions19611994. 7. South AfricaPolitics and government

19891994. I. Title.

DT 2247. B 56 H 63 2007

305.800968dc22 2006103110

eISBN 978-0-547-52522-8

v2.1017

Portions of this book first appeared, in somewhat different form, in Mother Jones,Harpers, and the Boston Review.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to reprint the following copyrighted material: Lines from the poem The Contraction and Enclosure of theLand by St. J. Page Yako. Reprinted by permission of the publisher, Perskor,from The Making of a Servant (Johannesburg, 1972), an anthology translated by P. Kavanaugh and Z. Qangule. The poem In Detention by Christopher VanWyk. Reprinted by permission of the author. Lines from the poem The Priceof Freedom by Mathews Phosa, as translated by William Mervin Gumede. Reprinted by permission of Struik Publishers, from Thabo Mbeki and the Battle forthe Soul of the ANC (Cape Town, 2005).

FOR

D AVID AND G ABRIEL

Looking into South Africa is like looking into the mirror

at midnight... A horrible face, but ones own.

BREYTEN BREYTENBACH

Preface to the Mariner Edition

Few countries on earth have ever undergone as dramatic and hopeful a political sea change as South Africa did at the end of the twentieth century. At the close of the 1980s, it was one of the worlds most notorious police states, for decades the object of protest marches and demonstrations around the globe. Thousands of black political dissidents were in jail, torture was routine, and only the small percentage of the population that was white could, in any meaningful way, vote. Nelson Mandela and other top African National Congress leaders had been in prison for more than a quarter of a century. And to all who cared about this beautiful and long-suffering country, it looked as if they would be serving out their life sentences.

But a mere few years later, in 1994, every adult South African could vote in the nations first democratic election. Mandela was elected President, and his coalition-government cabinet included people who had spent decades in prison or exileand the former head of the government that had once kept him behind bars.

Not only was the startling turnaround a peacefully negotiated one, it was one of historys most unexpected. In 1988, when I made the journey described in these pages, there was not a single journalist or commentator anywherenor, so far as we know, an intelligence agency of any governmentpredicting a democratic South Africa at any time soon. Every South African politician, activist, or academic I talked to believed that any real change was at least twenty or thirty years off, if then.

The changes that astonished the world, the first free election campaignwhich I witnessedand some of the bumps in the road South Africa has encountered since then, I have described in a new Epilogue. However, I have left the rest of this book entirely unchanged; its present tense refers to 1988, not to today. This, then, is a portrait of the country at the very peak of the state violence and repression that preceded one of the most remarkable transformations of our time. And, along the way, it is also a glance back at a crucial early episode of South African history.

A. H.

Beginnings

From a distance, Johannesburgs Alexandra township looks as if wisps of fog had collected above it, despite the sun-scorched day. Coming closer, I see that it is not fog but dust, for most streets here, unlike those in the white suburbs that surround Alexandra, are unpaved. This morning some fifty thousand pairs of feet are kicking the dust aloft as they make a pilgrimage over the hills, in long streams that converge on one spot. Seventeen Alexandra youths, from age twelve up, will be buried here today. They are victims of police bullets during six days of recent fighting in this township, one of the bloodier battles in South Africas long civil war.

It is March 5, 1986. I am heading toward the funeral with some white friends. They assure me we will be safe, but it is hard not to worry: our skin is the same color as those whose government shot the young men who are to be buried today. As white people on this emotion-laden day, wont we be targets for community rage? Adding to my uneasiness is the fact that South Africas division is one of class as well as race: the people Im with are in a larger convoy of white supporters of the resistance movement, all of whom are in cars, some of them new Audis and Peugeots. This line of cars is entering an overcrowded township whose black citizens mostly must travel by foot, van, or bus. As we drive into Alexandra, we pass its ramshackle bus station: cracked and battered open-air concrete platforms with destination signs whose very namesRosebank, Ferndale, Parktownspeak of the leisured white suburbs of swimming pools, tree-shaded streets, and well-sprinkled lawns. These are the places Alexandra residents commute to each day, to work as cooks, maids, and gardeners.

Through the open window of the car, I can smell the sewage ditches at the side of the road and hear the sound of dozens of small gasoline generators: in most of Alex, if you want electricity, you have to make your own. Goats, chickens, and an occasional cow wander the streets. Small, tin-roofed homes are cramped together. Desperate for housing, some families have even moved into a row of abandoned buses. Their wheels, stripped of tires, have sunk into the soil. Scattered about are reminders of recent street fighting: smashed windows, a few burnt-out cars.

Astoundingly, as our white caravan jounces slowly over the rutted road toward the funeral, we are cheered. Older people clap from the roadside. Children smile and wave from doorways. Young men give the clenched-fist saluteright arm extended, thumb outside fist. I see the same spirit a few moments later, when we walk into the overflowing soccer stadium where the funeral is to take place. Just outside the stadium is a large warehouse under construction, a skeleton of bright yellow steel girders. Several dozen young black men have climbed high up and are sitting precariously astride this framework. Despite a police order forbidding them, they hold banners with slogans like FORWARD TO PEOPLES POWER! Two white university students approach the structure, carrying their own banner of support. It takes them ten minutes to clamber up the steel beams while holding their sign; at every level, black hands reach down to help them up. Finally two Alexandra youths reach down from the topmost girder, take the students banner, and hold it aloft.