First Published in 2002

by Routledge Curzon

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge Curzon

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

RoutledgeCurzon is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

2002 Martin Ewans

Typeset in Imprint by LaserScript Ltd, Mitcham, Surrey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book has been requested

ISBN13: 978-0-7007-1589-3

To set it in motion, human pity needs precise and concrete facts. Set out in general terms, a record of the most atrocious crimes arouses no emotion.

Flicien Cattier

The vilest scramble for loot that ever disfigured the history of human conquest and geographical exploration. It was just robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a grand scale. The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look at it too much.

Joseph Conrad

European world expansion, accompanied as it was by a shameless defence of extermination, created habits of thought and political precedents that made way for outrages, finally culminating in the most horrendous of them all: the Holocaust Auschwitz was the modern industrial application of a policy of extermination on which European world domination had long since rested.

Sven Lindquist

In 1890, at the age of thirty-two, the novelist Joseph Conrad took up an appointment as captain of a river steamer on the Congo. On the face of it, this was a curious, almost incomprehensible, decision for a man who had only recently been appointed a captain in the British merchant marine. But his life at sea had turned sour, he had resigned his post and had been out of a job for the better part of a year. He was also intrigued by the reports of the expeditions which were at that time being mounted into the interior of Africa, and which seem to have revived within him the desire he had had from a very early age to go to that continent:

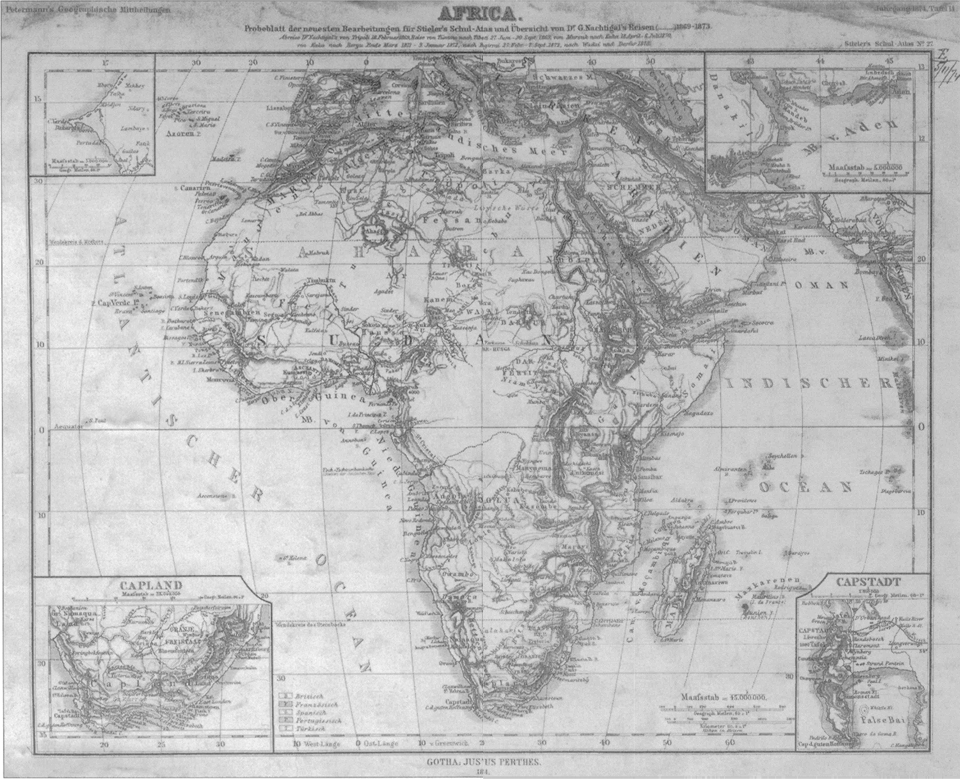

It was in 1868, when nine years old or thereabouts, that while looking at a map of Africa of the time and putting my finger on the blank space then representing the unsolved mystery of that continent, I said to myself with absolute assurance and an amazing audacity which are no longer in my character now: When I grow up, I shall go there ,

He enlisted the help of a distant cousin, his application to the authorities in Brussels was successful and he sailed for the Congo in the early summer of the following year.

Conrad stayed in the Congo for no more than six months. He had to endure a thoroughly unpleasant two hundred mile march to reach the head of navigation at Stanley Pool, and proceeded on arrival to fall out with the director of the local trading station. He was consequently never given command of what turned out to be a two-penny-half-penny river-steamer with a penny whistle attached and, after only a single voyage into the interior, he fell ill with fever and dysentery and came near to dying. He was fortunate to be able to secure his release from his contract, but was to suffer for years afterwards from recurrent fevers and other ailments.

Conrads experience in the Congo was to haunt him for years, and was distilled in 1902 into a minor masterpiece of English literature, his short novel Heart of Darkness. Essentially, Heart of Darkness is a subtle but overwhelming expos of Leopolds Free State, the enormities that were perpetrated there, and the attitudes of mind that gave rise to them. To grasp the nature of the Free State and the atmosphere pervading it, Conrads narrative is an almost indispensable introduction.

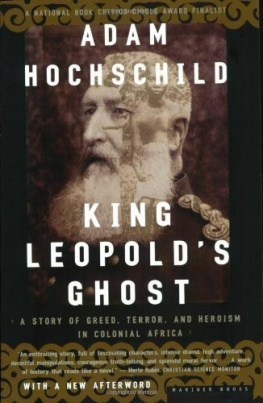

Leopold was, by any standards, a monster a man of immense ability, but one who was wholly devoid of principle and prepared to lie, cheat and deceive on a grand scale in order to achieve his ends. His private life and his treatment of his family became public scandals. His colonial ambitions, launched under a cloak of altruism and humanitarianism, were the product of a genuine sense of Heart of Darkness as racist in outlook, concerned to present Africa as a place where mans vaunted intelligence and refinement are finally mocked by triumphant bestiality, and driven by

the desire one might indeed say the need in Western psychology to set Africa up as a place of negations at once remote and vaguely familiar, in comparison with which Europes own state of spiritual grace will be manifest.

From an African viewpoint, this critique is understandable and, as a response to the perceptions of Africa generally held in Europe, both then and subsequently, wholly justified. Conrad, however, cannot be pinned down so easily. The Africans portrayed in the book may be little more than stereotypes, and Conrad concedes, through the narrator of the story, that his understanding of them may have been remote. Essentially, however, his subject is not the savagery and bestiality of Africans, but the corruption and degeneracy of Europe and Europeans.

At one level, Conrad is concerned to portray the sheer inhumanity that came to be the hallmark of King Leopolds African colony. His description of a chain gang working on a railway, for example, or of the grove to which exhausted Africans had crawled away to die, are passages of chilling description.

Black shapes crouched, lay, sat between the trees leaning against the trunks, clinging to the earth, half coming out, half effaced in the dim light, in all the attitudes of pain, abandonment and despair. This was the place where some of the helpers had withdrawn to die.

They were dying slowly it was very clear. They were not enemies, they were not criminals, they were nothing earthly now, nothing but black shadows of disease and starvation, lying confusedly in the greenish gloom. Brought from all the recesses of the coast in all the legality of time contracts, lost in uncongenial surroundings, fed on unfamiliar food, they sickened, became inefficient, and were then allowed to crawl away to rest. were scattered in every pose of contorted collapse, as in some picture of a massacre or a pestilence.

Other accounts were to show that such groves actually existed and were not just figments of Conrads imagination. Later, when the Inner Station is reached, the narrator finds that the residence is surrounded by poles on which are mounted human skulls a portrayal which is heavy with symbolism, but which is all the more telling because a Belgian administrator at Stanley Falls, one Captain Rom, was reported by an English visitor to have ornamented his flower beds with the heads of twenty-one natives killed in a punitive expedition.