2ND EDITION

Afghanistan

A New History

Martin Ewans

Sir Martin Ewans, former Head of the British Chancery in Kabul, puts into an historical and contemporary context the series of tragic events that have impinged on Afghanistan in the past half century. The book examines the roots of these developments in Afghanistans earlier history and external relationships, as well as their contemporary relevance, internally, regionally and globally.

The book reviews in detail the emergence of the Taliban, its ideology and its place within Islam, and examines Afghanistans relevance for several issues of global concern, notably the nature of Islamic extremism, the international drugs trade and international terrorism. This new edition also discusses the fall of the Taliban and ends with an analysis of the country post-Taliban.

Jacket Photograph courtesy of Mrs Anne Holt

First published 2001 by Curzon Press

Second edition first published 2002

by RoutledgeCurzon

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

RoutledgeCurzon is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

2001, 2002 Martin Ewans

Typeset in Stone by LaserScript Ltd, Mitcham, Surrey

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Biddles Ltd, Guildford and Kings Lynn

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 0415298261

List of Illustrations

(Between pages 212 and 213)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

1. British Museum.

2. Muse Guimet.

3, 4, 5. Frances Mortimer Rice.

6, 11. British Library.

8, 36. Anne Holt.

26, 27, 28, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37. Popperfoto.

Although every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyrights, in a few cases this has proved impossible.

INTRODUCTION

The Land and the People

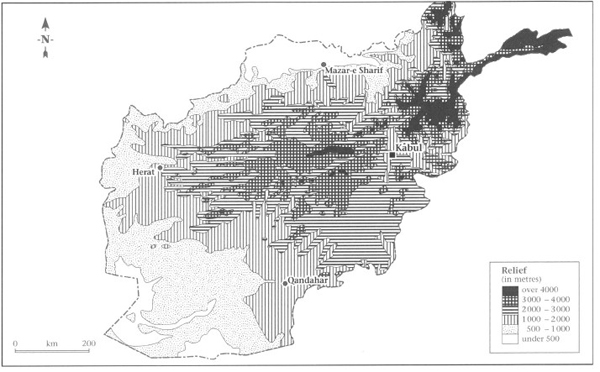

A fghanistan is a land of stark and rugged beauty, of snow-covered mountains, barren deserts and rolling steppe. Situated at the eastern end of the Iranian Plateau, it covers some 250,000 square miles, an area about the size of Texas, rather larger than France, rather smaller than Turkey. Some two-thirds of it lie above 5000 feet, and several of its mountains are among the highest in the world. The ranges that bisect the country may be likened to a hand outstretched towards the west, with the wrist lying on the Pamir Knot, the great tangle of mountains at the western extremity of the massive arm of the Himalayas and Karakorams. At the palm of the hand lies the Hindu Kush, the killer of Indians, possibly so called in recognition of the Indian slaves who met their deaths as they were taken across its passes to the khanates of Central Asia. Beyond the Hindu Kush is the Koh-i-Baba, a complex of mountains and uplands which gradually tapers towards the west into the fingers of the Band-i-Turkestan, the Safed Koh, the Siah Koh and the Parapomisus Range, each in turn subsiding as it approaches the Iranian frontier. Other fingers run in a more southerly direction, the Suleiman Range close to the eastern frontier with Pakistan, the Kirthar Range which stretches into Baluchistan, and the Paghman Range which provides a scenic backdrop to the countrys capital, Kabul. Only to the north and the south-west of the country are lowlands to be found, as the mountains give way in the one direction to the plains of Afghan Turkestan and the banks of the Amu Darya, and in the other to the basin of the Helmand River, enclosing in its semi-circular course the barren expanse of the Dasht-i-Margo, the Desert of Death.

Afghanistan is a land-locked country, with frontiers that were mostly demarcated towards the end of the nineteenth century. To the north, its borders with the Republics of Tajikistan, Usbekistan and Turkmenistan run for some thirteen hundred miles, westwards from the Pamirs along the Amu Darya and then across country to the Hari Rud, the river that marks the northern end of its frontier with Iran. In the far north-east, high in the Pamirs, is a fifty mile border with China, from which runs the so-called Durand Line, the frontier that divides Afghanistan from Pakistan. This winds its way south-westwards for some eight hundred miles and then swings westwards for a further seven hundred, skirting the Helmand valley and meeting the Iranian frontier south of the Hamun, the complex of lakes and marshes into which the Helmand finally drains. The Afghan-Iranian border then runs northwards for nearly six hundred miles, until it meets the Hari Rud.

The Hindu Kush marks the watershed between the Indus and Amu Darya basins, and is part of the mountainous divide that separates Southern from Central Asia. Only on the western side of the country is there an easy route between the two regions, guarded by the ancient city of Herat. The dozen or so passes across the mountains are closed by snow for some six months of the year and only one of them is below 10,000 feet. Despite their difficulty, however, they have been routes of migration and conquest, and have been crossed by successions of merchants and pilgrims, lured from Central Asia and beyond by the material and spiritual riches of the Indian Subcontinent. The even more ancient city of Balkh, now an expanse of jumbled ruins, owed its position on the Silk Route between China and the Mediterranean to its proximity to the most accessible of these passes. Only in recent years has a tunnel been driven below the Salang Pass, creating an all-season road from Afghan Turkestan to the capital and the lands beyond. To the east of the country, the routes to the Indian Sub-continent lie through another line of passes, of which the Khyber Pass is merely the best known.

Afghanistan has a continental climate, cut off from the Arabian Sea monsoon by the mountains lying to its south-east. Its summers are hot and dry and its winters harsh, with great daily and seasonal variations. Rainfall is light, water is scarce and most of the country barren. From the air it resembles a vast moonscape, with only the occasional green of an oasis or a narrow patch of vegetation snaking along a valley floor. All but a fraction of the land area is uncultivable, although there is some rain-fed agriculture in a relatively few fertile areas, and the rivers, nourished by the melting snows, lend themselves to irrigation, at which the Afghans are adept. Many valleys have their juis, the artificial watercourses that wind along the hillsides and mark the boundaries between the barren uplands and the fields below, while elsewhere there are karez, man-made underground channels which run from the edge of the water table to cultivated land, sometimes over considerable distances. The bulk of the population derive their livelihoods from agriculture and pastoralism, or from crafts that are dependent on these activities. Most of the agricultural land is given over to food grains, principally wheat, although cotton, fruit and, latterly, opium, are important cash crops. Although with regional variations, large land holdings have been few and smallholdings the norm, a relative egalitarianism that has meant that the extremes of hunger and malnutrition are not normally as visible in Afghanistan as in some other Asian countries. Such is the marginality of much of the land, however, particularly in the centre and north-east of the country, that severe famines have occurred from time to time. Grazing land is also limited and much of it is only seasonal, so that some two-and-a-half million nomads, the