Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org

Afghanistans Islam

Afghanistans Islam

From Conversion to the Taliban

Edited by

Nile Green

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2017 by The Regents of the University of California

Suggested citation: Green, Nile (ed.). Afghanistans Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban . Oakland: University of California Press, 2017. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.23

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Green, Nile, editor.

Title: Afghanistans Islam : from conversion to the Taliban / edited by Nile Green.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press,

[2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016036746 | ISBN 9780520294134 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780520967373 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: IslamAfghanistanHistory. | MuslimsAfghanistanHistory.

Classification: LCC BP63.A54 A39 2016 | DDC 297.09581dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016036746

Manufactured in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Nile Green

Arezou Azad

Nushin Arbabzadah

Jrgen Paul

R. D. McChesney

Waleed Ziad

Amin Tarzi

Sana Haroon

Faridullah Bezhan

Simon Wolfgang Fuchs

Ingeborg Baldauf

Sonia Ahsan

Alessandro Monsutti

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

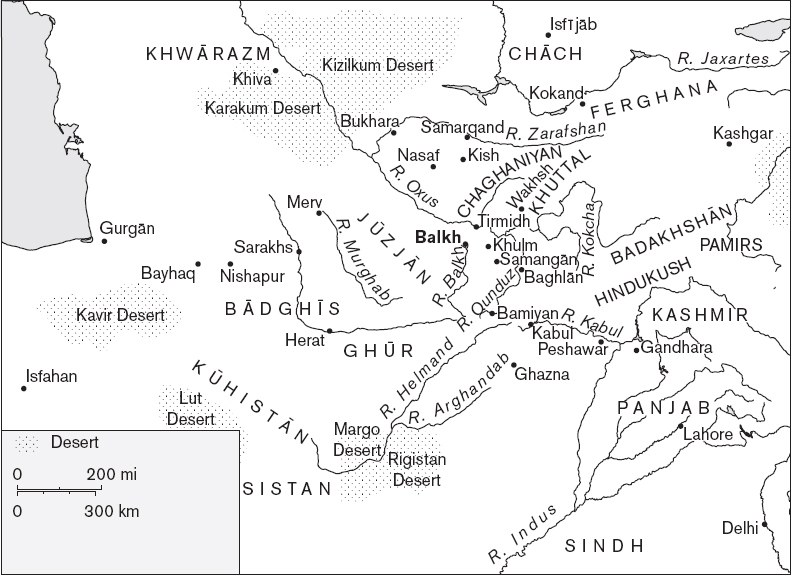

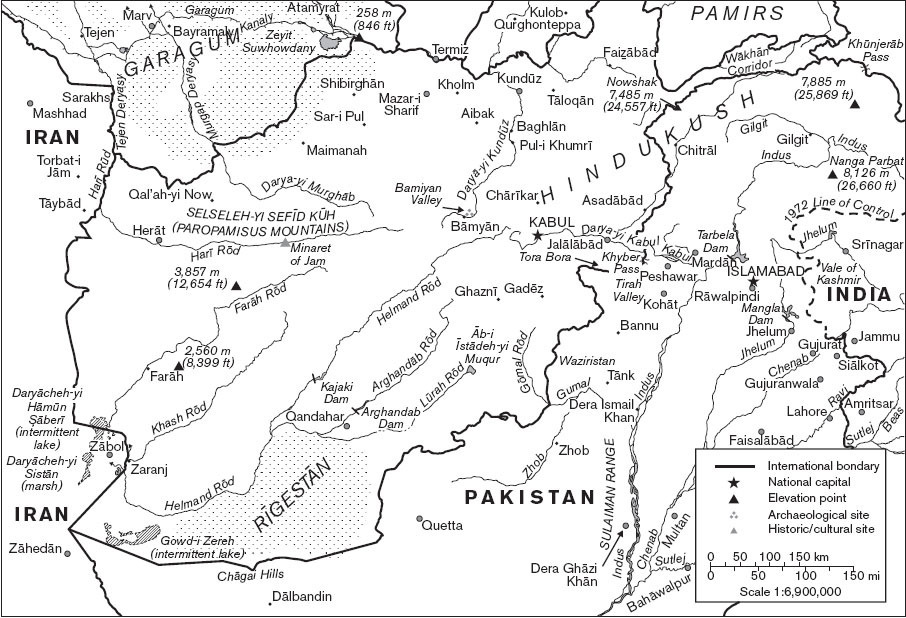

MAPS

FIGURES

TABLES

. Medieval Afghanistan and its regional context (Balkh Art and Cultural Heritage Project, University of Oxford). Global 30 Arc-Second Elevation Data Set (GTOPO30) 1996 US Geological Survey. Made with Natural E. Courtesy of Arezou Azad.

. Modern Afghanistan and its regional context.

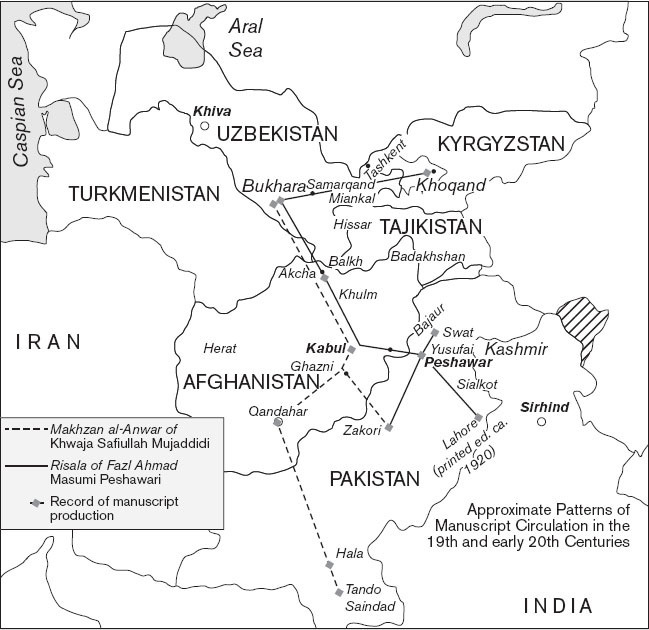

. The Naqshbandi legacy of Safiullah and Fazl Ahmad. ( Waleed Ziad)

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Religion has been one of the most influential cultural, social, and political forces in Afghan history. In premodern times, a variety of different versions of Islam spread through the uneven geography of what later became Afghanistan, echoing its ethnically varied demography through similarly variant patterns of religious practice. In modern times, these many versions of Islam served as powerful sociopolitical resources, providing idioms and organizations for both state and anti-state mobilization. Even as religion has been deployed as the national cement of a multiethnic emirate under the Taliban and then an Islamic republic under their recently elected successors, Islam has been no less a destabilizing force in Afghan society. Yet despite the universal recognition of the centrality of Islam to Afghan society in past and present, Afghanistans Islam has attracted strikingly little sustained study. Beyond a few monographs devoted to particular moments or movements (predominantly the mujahidin and Taliban), there exists no survey of the developmental trajectories of Afghan religiosity across the course of history. The scholarship becomes particularly patchy for the period before the Soviet invasion of 1979, making it difficult to position the fundamentalist movements from the 1980s onward in relation to earlier patterns of religious activity, whether local or transnational.

To begin to fill this gap of understanding, this volume brings together international specialists on different periods, regions, and languages to develop a more comprehensive, comparative, and developmental picture of Afghanistans Islam from the eighth century to the present. The aim of the eleven chapters is to collectively provide an in-depth, critical, panoptic overview of the major developments and transformations of Islam from the early medieval period to contemporary times in the territories that today make up Afghanistan. Given the variety of sources and languages required for such a projectPersian, Pashto, and Uzbek, as well as Arabic and Urduthe contributors have been selected on the basis of their previous research with both spoken and written testimony in these languages. Since the authors are specialists on a range of different periods and movements, their case studies of a variety of Muslim religious forms will allow us to see beyond the unifying rhetoric of Islam into its disparate and even fissiparous expressions.

It is for this reason that the introductory chapter speaks of versions of Islam, in the social-scientific plural rather than the theological singular. In part, this usage is an attempt to move beyond facile and emic notions of the singularity and unity of Islam. Stepping outside such insider discourses helps observers analytically recognize the religious differences that have so often proved a source of, or justification for, social discord and violence. In a volume that brings together scholars from the humanities and as well from the social sciences, this pluralistic formula allows us to recognize also the cultural variety of Afghanistans rich religious heritage. The aim, then, is to walk the tightrope between critical distance and sympathetic appreciation of a religious history that, for different groups, has been a source of solace as well as of oppression.

There are certainly difficulties with using the rubric Afghanistan to bring together studies of the medieval and modern eras. As a nation-state Afghanistan acquired its shape and name only between the later eighteenth and the later nineteenth century. In the period dealt with in the earlier chapters in this book, Afghanistan would have been a meaningless term: indeed, the label seems not to have been officially adopted in the region itself till the 1870s. The region had previously been understood as a congeries of different territories, such as Khurasan and Turkistan, which were sometimes governed by the same ruler and more often divided among different rulers. Nonetheless, the collective national label Afghanistan is helpful in allowing us to easily conjure the geographical space under scrutiny in this volume and in enabling us to focus on its religious transformations through time. For as the following chapters show, the later nation-state of Afghanistan was heir to the religious institutions, authorities, and practices that emerged in its former fragmentary parts.