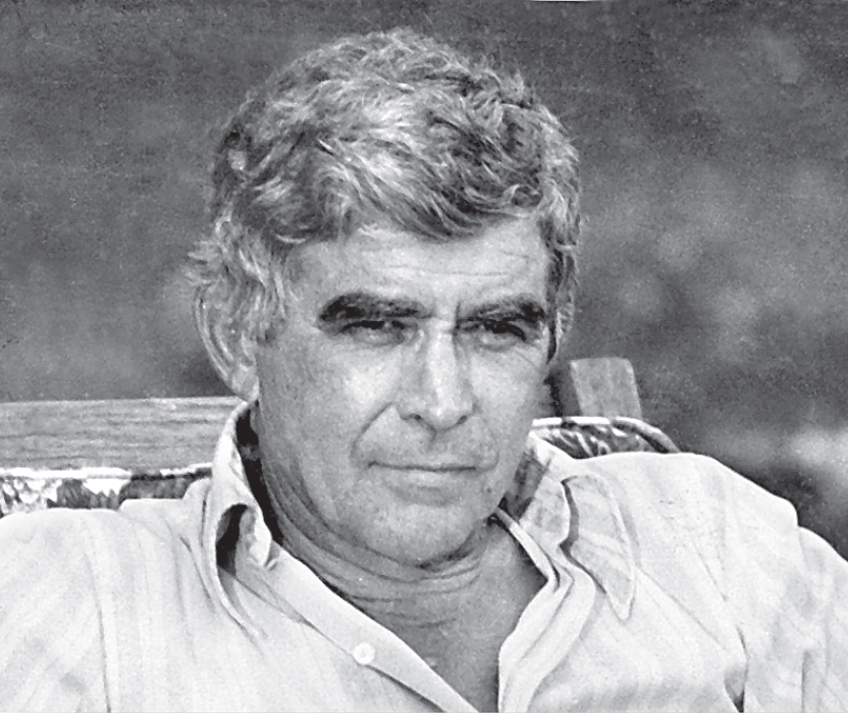

H e died first, quickly and quietly. It was like my father to outwit my mother, even at the end. Cancer had sprouted in his lung and traveled slowly upward, until it had found an auspicious nesting place on his brain stem. My father, who despised doctors, could probably have bought himself some significant time had it not been for his overweening love of crossword puzzles. He spent his days fastened to a corner of the living room couch, a crossword puzzle laid out before him on the coffee table. To his left, on the dark wood end table, rested his props. A pack of Pall Mall cigarettes, neatly opened, the foil exposing the slim brown and white soldiers stationed within. A heavy gold-plated ashtray with a miniature eagle saddled in such a way as to offer a resting place for the burning cigarette. The requisite silver lighter lay nearby, square and heavy and satisfying to flip open and ignite. A cup of coffee stood innocently by, sipped carefully in the morning, but often left untouched for long periods of time, until the day softened into dusk, at which point it was replaced with a glass of vodka. This beverage, served in a slightly dirty glass with only the suggestion of ice, never stood idly by. It was relished by my father, and his hand left the coolness of the glass only long enough to attend to a challenge on the crossword puzzle before him.

One day, he leaned in to address the problem of a particularly perplexing word and realized he couldnt make out the characters, despite his best efforts. The vision in his left eye would not adjust itself, and the words swam in front of him, causing increasing frustration. My father pulled himself up from his customary place on the couch and made his way slowly to the small bathroom located under the stairwell, where he studied himself in the mirror over the sink. Then he walked back into the living room and peered at the mantel, searching for the small white first aid kit that had rested there, mostly undisturbed, for decades.

Grasping the first aid kit, my father walked into the back of the house, where a long table stood in the middle of the laundry room. He placed the box on the table and quickly withdrew the necessary items: gauze pads and surgical tape. Then he moved into the bathroom off the kitchen and, locking the door behind him, began in earnest to solve the problem of his errant left eye.

This was the sight that greeted my brother Joe when he visited our father later that winter afternoon, and how terrible it must have been for him. All alone, he stood in the middle of the living room and studied his eighty-three-year-old father sitting before him on the couch. The year was 2004, but the old man looked like someone who time had forgotten, peering stoically forward, the left lens of his glasses patched with white gauze and crossed twice over with surgical tape. Joe stared at our father and said, Jesus, Dad. Joe was no fool and had an intuitive understanding of the game about to be afoot, but neither was he a glutton for punishment, so he tried to slow things down.

What the hell happened to you? he asked, sitting across from our father on a black and red floral ottoman, a permanent depression at its center, so that one had no choice but to sink into it. Joe, sunken, looked miserable, as he leaned forward, arms braced on his thighs.

Our father lit a cigarette, inhaled deeply, and said, Couldnt do the crossword puzzle. Frustrating as hell.

Joe said nothing. His love for his father was complicated, and often ran along parallel lines of anxiety and devotion. When in our fathers presence, Joe felt himself helplessly reduced to a kind of childlike insecurity, hesitant to be completely himself with this man, for whom he would do anything. As a result, they often sat together in silence, Dad working on his crossword puzzle and Joe reading the paper. Today, however, Joe found the silence intolerable, and because he could not bear the heaviness that lay over the room, he spoke more boldly than was his custom.

I think we should visit the ophthalmologist, Dad, and see whats going on. See if we cant get this thing corrected so you can get back to your crossword puzzles.

My father raised an eyebrow and asked, You think so? Think its an easy enough fix?

The two good-looking men, father and son, studied each other. Deceit did not suit their relationship, which was unlike any other in the family. Joe and my father shared a relationship in which each attached a special value to the other, so that in many ways theirs was a secret, unspoken affection, one that defied articulation. Joes need for his father was primal, the fathers need for his son plaintive. This chemistry produced an allegiance at once tenuous and sacred.

After a time, my father looked up from his unfinishable crossword puzzle and fixed his good eye on his son.

Shit, he said, in acquiescence.

* * *

THE PHONE RANG in the bedroom of my apartment in West Palm Beach, where I had retired to take a nap between shows. The tour of Tea at Five, a one-woman bio-drama in which I played Katharine Hepburn in both her youth and her dotage, had begun to take its toll. This was precious time for me, since my efforts on the stage were considerable, and when two performances were demanded in one day, it was imperative to lie as still as possible for as long as possible so as to be able to seduce the audience at the evening performance into believing that I was both much younger then I actually was and, fifteen minutes later, much, much older. Therefore, I hesitated before reaching over and then decided, in a moment of curious karmic resolve, to pick up the phone and answer.

Hello.

Kate, this is your brother Joe.

The curious formality with which my brother always addressed me had the odd effect of bringing me instantly to attention. My heart skipped a beat, as it did whenever Joe called. This was because Joe was not given to phone calls of a purely social nature. I knew he was not inquiring after my well-being. I intuited, instead, that my brother had something important to tell me and that I had better prepare myself.

Whats up, Bobo? You sound grim, I said.

Somethings up with Dad, Joe replied, shortly.

It was this very curtness of tone that alerted me to the seriousness of the matter at hand. It was not Joes style to deliver bad news with finesse. He was not one to measure the sound of his remarks, nor was he likely to put himself in the other persons shoes. When darkness was my brothers message, he delivered it with the blunt force of a metal hammer.